He survived a Nazi work camp to shape the world of modern film

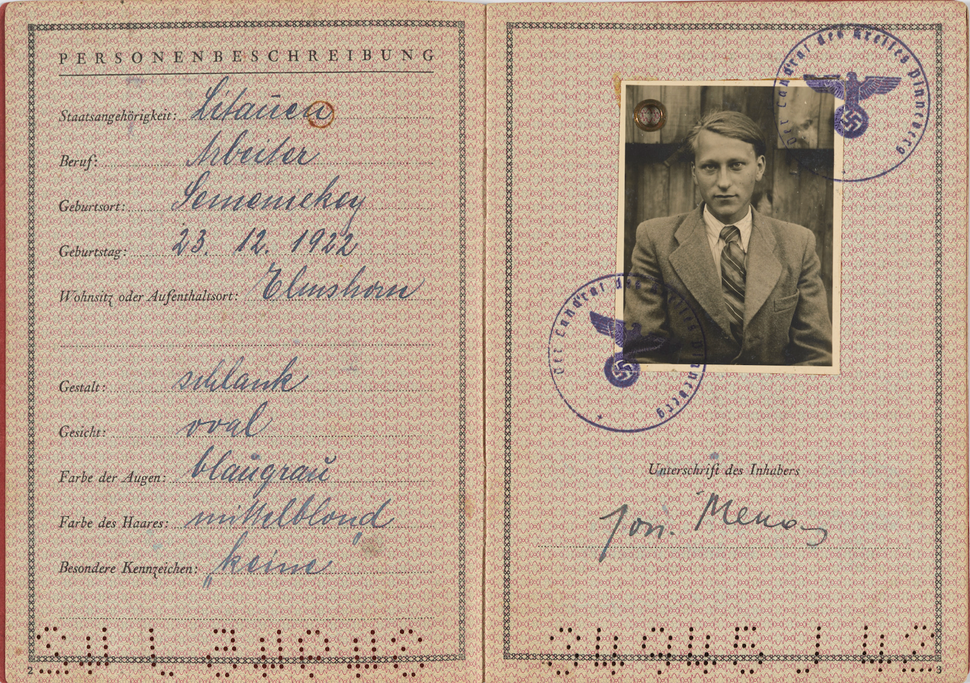

Temporary Passport: When Jonas Mekas arrived in New York City, he had survived a Nazi work camp and several years as a refugee Courtesy of The Jewish Museum

In October 1949, Jonas Mekas arrived in New York City broke and nearly broken.

The Lithuanian artist had survived a Nazi work camp and several years as a refugee, and was supposed to travel on to Chicago where a job in a bakery awaited. But the buzz of New York City energized him and so he stayed. Thus began a prolific career in which Mekas explored time and place.

This incessant exploration is at the core of the Jewish Museum’s newest exhibit “Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running.” It’s the first time an American museum has featured a survey of the filmmaker, poet and critic who helped shape the avant-garde in New York City and beyond.

“There is something about what he’s doing and how he did it that allows you to connect with his work. Through his own searching for meaning, he helps you do the same thing. Like all great art it gives you something to do on your own. It helps move you through life,” said guest curator Kelly Taxter, who worked with Mekas on previous exhibitions.

The show, which includes 11 films, archival materials and photography, spans the entirety of Mekas’s career, beginning with his first major work “Guns of the Trees” and ending with his last work “Requiem,” which he worked on until 10 p.m. the night before he died in 2019.

Man With a Camera: The Jewish Museum’s Jonas Mekas retrospective spans the entirety of his career, beginning with his first major work “Guns of the Trees” and ending with his last work “Requiem.” Courtesy of The Jewish Museum

Born in 1922 in Semeniskes, a small farming village in northeast Lithuania, Mekas composed his first poem about farming life when he was six. His youth was cut short at age 16 when the Red Army rolled into Lithuania. He soon began distributing anti-Soviet publications.

When the Germans invaded two years later Mekas continued his clandestine work. This time he transcribed and distributed news bulletins from the BBC. Soon after the Nazis arrested Mekas and his brother Adolfas. They were sent to a forced labor camp from which they later escaped.

After spending one year in the work camp and four years in Displaced Persons camps, the brothers sailed to the U.S. on a ship with more than 1,200 refugees. They settled in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Although Mekas grew to feel at home in America, his feelings of displacement never abated.

“He certainly made a fierce home in New York City. He was very much a citizen of this place. I think for him he was not a nationalist, but rather he was always somehow here and there,” Taxter said.

Indeed, his 1972 “Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania” shows just how deeply his refugee experience shaped his art. Drawn from his experiences of living through both the Soviet and Nazi occupations of Lithuania, the film considers loss, memory and a yearning for his birthplace.

“There is also a universality to his work,” said Taxter. “He was someone who was displaced for five years. And he was helped by the United Nations. He could come. Now people can’t. That’s something to really keep in mind as you are seeing this work and understanding this project.”

A Still From ‘Walden.’ Jonas Mekas’s 1968 diary film featured featured footage of his friends and acquaintances including John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Courtesy of The Jewish Museum

Many of Mekas’ films feature the artists and celebrities he met throughout his life. The poet Allen Ginsberg recites his work in “Guns of the Trees.” Mekas’s 1990 “Scenes from the Life of Andy Warhol,” shows the artist in the company of Mick Jagger, Lee Radziwill as well as Caroline and John F. Kennedy.

Mekas, who wrote many film critiques, was also the founder and co-founder of numerous artist-run cooperatives and distribution networks.

In 1954, he co-founded Film Culture, the first journal of American film criticism. He also wrote for “Movie Journal,’” the Village Voice’s first critical column on cinema. And in the late 1960s, he presented the screening and conversations series “Avant Garde Tuesdays” at the Jewish Museum.

“He essentially created the experimental film community in New York City and later worked with filmmakers across the country, including San Francisco and Philadelphia,” Taxter said.

A Collection of Mekas’s Stills: By the time he died in 2019, Mekas had made 93 films and videos. Courtesy of The Jewish Museum

For Mekas, the camera truly never stopped running. By the time he died in 2019 at age 96, he had made 93 films and videos. Each one is a record of his life, a resource for his art, and perhaps most of all, a reflection on the passage of time.

“His last film, ‘Requiem,’ shows human suffering for the first time,” said Taxter. “All his films before are celebratory. They show sadness and longing, but they’re hopeful. This one, and this is strictly my interpretation, seems to be a meditation on his own mortality.”

“Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running” runs through June 5, 2022, at the Jewish Museum.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO