It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s a book about Superman’s complete Jewish history!

‘Is Superman Circumcised?” by Roy Schwartz Courtesy of McFarland Publishers

A lot of people know that Superman’s creators, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, were Jewish. But according to Roy Schwartz – author of “Is Superman Circumcised?: The Complete Jewish History of the World’s Greatest Hero” – the question of Superman’s Jewishness hasn’t been discussed deeply enough.

“Many things that are relevant and interesting have been overlooked,” Schwartz told the Forward. “Most of the attention has been given to his formative years, and there is a lot to discover, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s, years rife with Jewish themes and symbolism and signifiers and even stories lifted wholesale from the Bible. People should not assume that they have heard everything there is to hear about it.”

‘Is Superman Circumcised?” by Roy Schwartz Courtesy of McFarland Publishers

Throughout the book’s 318 pages and 40 pages of notes and bibliography, Schwartz approaches the subject with an academic lens and a fan’s passion, with text-parsing that would have impressed the rabbis of the Talmud. Examining overlaps and intersections between the character and faith, American culture and history, he reads Superman as biblical character amalgam (a Moses-Samson hybrid with, depending on the story, a healthy dose of Jesus); as immigrant narrative (trying to fit into and succeed in a foreign society); as a golem and more, complete with citations of comic books in which Jewish topics or images are included.

For example, “The Death of Superman” comic book (Superman #149, November 1961) is a noncanonical story in which Lex Luthor finally managed to kill the Man of Steel. Luthor is captured, put on trial in a glass booth, and sentenced to death. Schwartz says this is “one-to-one modeled after the Eichmann Trial,” which was underway when the book story was published.

Schwartz also compared the Superman story to the film “The Jazz Singer” – about the son of a cantor who hides his Judaism to find success, and eventually feels torn between his two worlds. And in the 17-page Superman #247 (January 1972), Schwartz points out, readers are reminded that Superman is an immigrant, “paralleling his origin with that of an undocumented boy from Mexico sent by his dying father in hopes of a better life.”

“He is Clark Kent and Superman; he is the ethnic guy with the Hebraic name Kal-El who came to America, changed his mannerisms and appearance. He tucks his tallit down into his suit, and he goes around the world like a gentile. So it’s sort of like the ultimate assimilation/assertion fantasy, the ability to decide which part of you should interact with society at any given moment. What is more American than being an ethnic immigrant, and bringing the gifts and uniqueness of your cultural heritage to the greater benefit of the American society?”

Over the years, he added, Superman has been claimed by Buddhists, the LGBTQ community, Christians and more, which he calls “a testament to the strength of the character, and does not in any way invalidate anything else…. Part of Superman’s resonance is that everybody could see themselves reflected in him.”

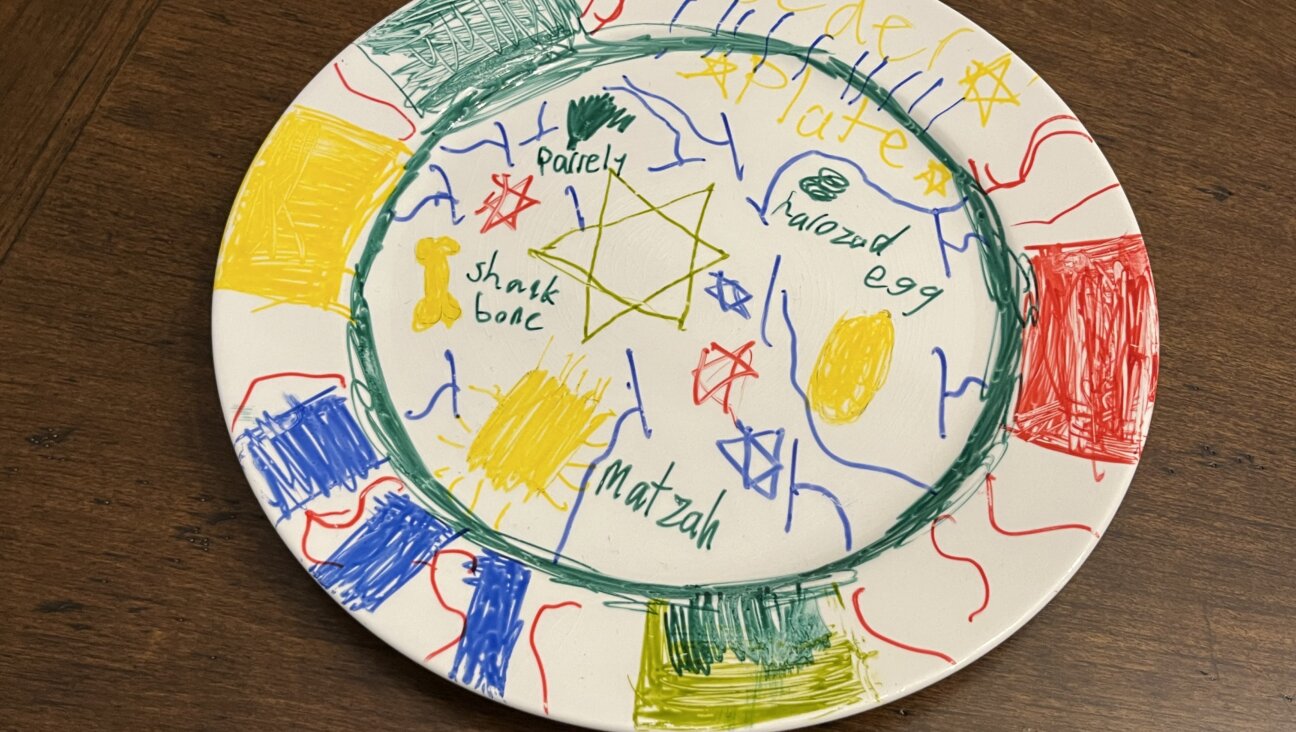

One direct Jewish influence comes from Superman #400 (October ’84), which portrays a family celebrating a holiday called Miracle Monday that is modeled after the Passover Seder. The scene refers to celebrating freedom on a night that’s different from all other nights, and which includes the call to “let all who are hungry come and eat,” Schwartz writes.

Golems, anthropomorphic beings in Jewish folklore, also take up a big chunk of space. For instance, in 1998’s Superman: Man of Steel #82, Superman goes back in time to World War II, and defends the Warsaw Ghetto. “Throughout, both Jews and Nazis recognize him as a golem,” Schwartz writes.

Although cultural lore is replete with characters who have speed, super-strength or can fly, “There’s one thing that Superman does better than all of them: inspire hope. He reminds us to be better people,” Schwartz said.

“Long before he was the Man of Steel, he was the champion of the oppressed,” Schwartz said. “The people he fought early on were abusive husbands, racketeers, corrupt politicians, slumlords, people who bully or prey on the weak and helpless of society.”

To wit, Schwartz said that what Superman “would have absolutely addressed is the groundswell of antisemitism around the world” that he says is “conspicuously missing” from mainstream comics today. While comic books are addressing racism, homophobia, transphobia, Islamophobia and other prejudices, “there’s not a whisper about antisemitism anywhere. And that silence speaks volumes to me.”

“I think Superman would remember to approach everything with compassion, and with understanding, remembering that we all have heartbeats,” Schwartz said. “We are all human beings, even if we’re from different planets. With that approach of understanding, compassion and goodwill, all these problems that at first seem intractable often seem very reasonably solvable. That is the great hope that he inspires.”

“Superman was created as a bugle or shofar, as a tool of inclusion as a bridge between cultures,” Schwartz said. “And I think nothing would have made Siegel and Shuster happier than knowing that he is connecting so many people from so many different backgrounds in their love for their character and what he represents.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO