Musician Yoke Lore thrives as a pandemic hermit. Here’s what he’s gotten done

Adrian Galvin, aka Yoke Lore By Emma Mead

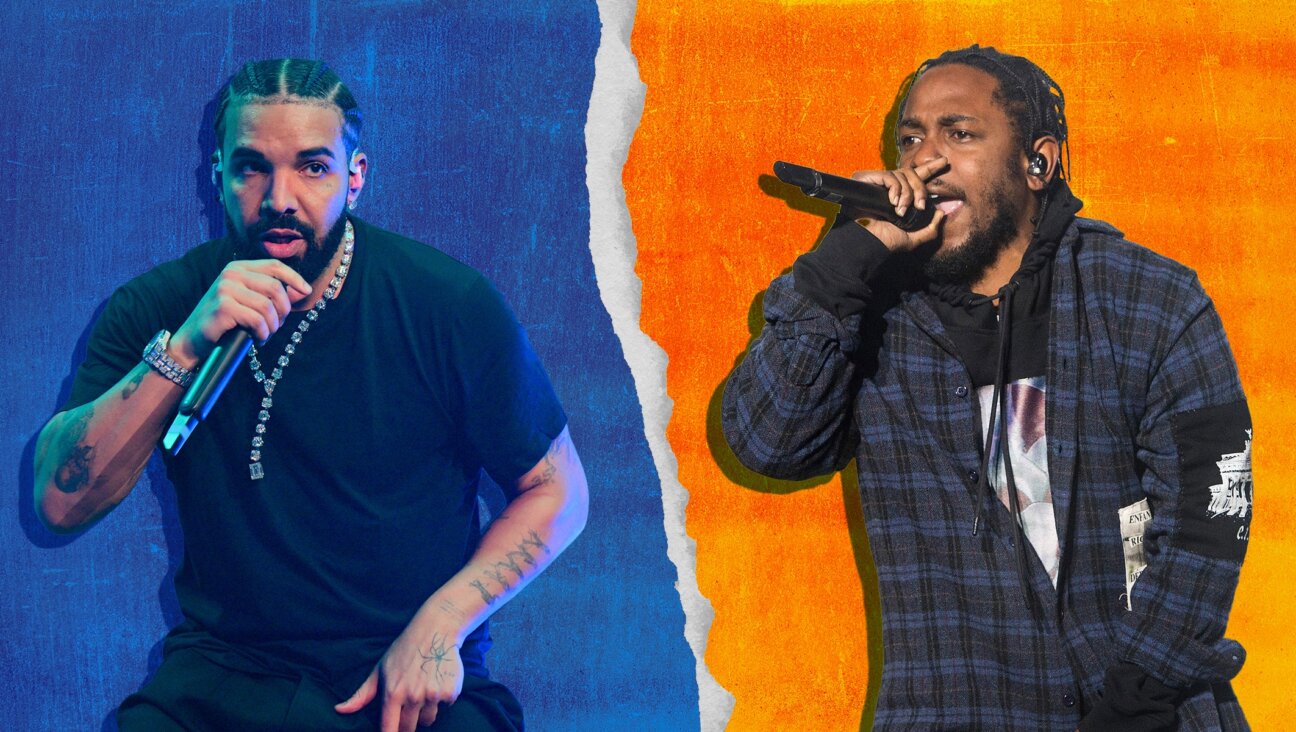

The last real concert I attended, before the pandemic hit, was at the Sinclair in Cambridge. I was seeing a band called Yoke Lore — really just one guy, who plays electronic-inflected, danceable banjo music. I’d just gotten into the band, and was listening to a few songs on repeat, but I didn’t know much more when I decided to go. Then Adrian Galvin, aka Yoke Lore, walked on stage, picked up his banjo, and began wailing on it like it was an electric guitar. It was, to date, among my favorite concerts ever, and that’s saying something given I spent two years working for the Sasquatch! music festival.

While I adore folk music, I realize not everyone is instantly excited by the visual of someone rocking out on banjo. Yet Galvin’s music doesn’t sound like what you think about when you think of the banjo — in fact, when I first started listening to Yoke Lore, I had no idea he was playing a banjo. Instead of twangy bluegrass, his songs are heavy on soft vocal harmonies, brashly strummed chords, and thoughtful lyrics. Despite being extremely soft-spoken, Galvin has a lot of stage presence and charisma, and he spoke thoughtfully about each song before leaping into a high energy rendition, bouncing around the stage.

Yoke Lore at a concert in St. Louis, pre pandemic. By Nick Pavlakis

Galvin’s passions lie not only only music but also in philosophy and social justice, which is immediately clear when he speaks. Within the first few minutes of our conversation, he was explaining an attempt to write his thoughts on the iconic 1922 German Expressionist horror film “Nosferatu” and its significance for Weimar Germany into some song lyrics. “It went off the rails a little bit, intellectually,” he said.

Before the pandemic, he had bounced between New York and Los Angeles, living a life out of a bohemian movie; he grew up on the Upper West Side and his whole family works in theater. Now, however, he’s settled out west full time, where he has dabbled in a bit of Hollywood work, scoring his girlfriend Kelly Oxford’s new film, “Pink Skies Ahead.” Galvin is, annoyingly, thriving in the pandemic’s isolation — he told me he hasn’t been so creatively productive in years. (He also promised me a new, full-length album soon, however, so I’ll forgive him.)

I spoke with Galvin for far too long — again, I’m a fan, and I milked it — about his creative process, his personal philosophy, and how he almost ended up going to Harvard Divinity School with me. The interview has been edited and condensed to omit that last bit.

What’s it like living in LA after a lifetime in New York? Has it changed your creative process at all to be in California now?

It’s more isolating, in a way that is both good and bad for my creative life I think. You don’t see anyone in LA. It’s car culture, there’s no street culture out here. Not that that’s a terrible thing. But it’s just something that New York City has a lot of.

Not having that really forces me further into myself. You have to really contend with yourself, because there’s not as much that you can focus on and be distracted by. There’s just so much in New York to do all the time; every time you step out of the house there’s people and things and street parties — it’s a big community. Here, it’s way more of an individual lifestyle.

And honestly, that’s kind of why I came out here. Because I’m slightly hermetic, and I kind of enjoy my isolation.

Can you talk about your spiritual practices? I know your mom is a yoga teacher and it seems like contemplation is a big part of your life.

My mother is Jewish and my father is Catholic, and I was raised both. They’re both pretty devout people, and we were both bar mitzvahed and confirmed. We went to church every Sunday and synagogue every Friday. That’s where I’ve always encountered the biggest questions and the best stories.

My spiritual practice is very wrapped up in my intellectual life. I was actually just writing a song that I’m working on, called “Shake,” and I realized that I’m really writing about this idea of shaking as in, shake yourself out of a rut, or out of stagnation.

I was writing about Weimar Germany and “Nosferatu,” it was really esoteric, but I was writing about how someone can incite a fire inside of you. I came back to the story of Adam and Eve, and they were kind of given this spark by Lucifer, the Light-Bringer, and it kind of opened their eyes and doomed them at the same time. And this spark of life is this “shake” that I’m trying to define, that for better or worse brings us to a new emotional and spiritual place within which we have to deal with our new enlightened self.

Adrian Galvin on a carpet By Wes & Alex

So where have you been finding that “shake” or spark in the past year? I know that’s something I’ve been struggling with.

I think I go back to books a lot. I’ve been reading the autobiography of Anais Nin. She’s a force of nature — wow. I read a lot of sci-fi, I’ve been reading some collected stories of Isaac Asimov, some William S. Burroughs.

Opening a book is like — you’re in your own room all the time, you only know these four walls, you only know what the color of the ceiling is, and you open a book and it’s like going into a whole other room and you’re like whoa, there’s all of these other paintings on the wall in this room. So I go to books to find new worlds to be in.

I need to read more.

It’s hard! It’s not that it’s unsupported by our culture, but it’s not made essential. They make it a lot easier to do other things.

It seems like your whole family is in the arts, or at least your siblings, Noah Galvin and Emma Galvin. Was that a big part of your upbringing? How did you guys all find yourselves in the creative world?

Yeah, it kind of just happened. Well, I know how it happened — the genes. I have two grandmas that were both painters, my aunt is a painter, I had another great-uncle who was a sculptor. My father was an actor and my mother was a director. My sister is an actor, my brother is an actor. I think our genes are just like that. My grandpa used to putter around and sing show tunes to himself — it’s always been part of our familial zeitgeist.

Both my parents, at some point, were given the idea that art was the highest form of expression, that art was the highest value of human activity. I think they really impressed upon us the notion that you could create the world around you with the things that you put into it. I think that was intensely influential for me. We could become good Jewish lawyers or doctors, but the onus was placed on us to participate in a more macrocosmic way.

Why did music end up winning out for you?

I was singing before I could talk. My brother was on Broadway by the time he was like, 10. I started playing drums when I was 9 because my sister had started taking drum lessons and she was just super cool. I was a very energetic kid, a lot of hyperactive tendencies, and I think my parents were like, “What a gold mine, just stick the kid in the basement with a drum set and we’re home free.”

I always felt myself a little bit on the outside of the conversation of being creative when I was little. I was looked at as like, a boy, who was always wrestling and running around. So I think the drums were the first time I felt like I could be part of that world of dance and music and a more sensitive relationship to the world. Not that drums are super sensitive, but they were my gateway drug.

Then how did you find your way to banjo?

I found banjo in college because it was kind of like a drum. I was interested in it because I’m a big history nerd, and banjo plays a very specific part in American history. And I love it. A guy named Roscoe Holcomb is my favorite banjo player. He has the most haunting voice in the whole world, it’s like listening to a beautiful broken air conditioner or something.

I think it was something I could really put myself into and make my own. The guitar has been played every which way. I’m fine at guitar, but there are 9-year-old virtuosos running around who play guitar behind their backs and with their teeth and left-handed, and I’m not going to play that game.

I know you did some livestreams early in the pandemic. How have you been managing this new paradigm?

I’m kind of a Luddite. I don’t really want to do more livestreams. For a while, I was resisting the reality of having to be separated from my fans and from performing. But more recently, I have accepted it and found value in it — I’m into my isolation.

I was worried at the beginning that I was going to lose momentum and presence in my listeners’ world. But they’ll be there, or they won’t be. This is a time that everyone is forced to be with themselves. I think you have to meet that head-on.

I want my art to be really good! I want it to do things. I can’t do that if I’m running around with my head cut off trying to find the input button to set up the mic on my livestream. Certain people are super good at that! But I needed this time to come back to myself and start writing again in a really confident way.

It feels to me like your style has changed a lot since “Safety.” And now you’ve rereleased that first EP “Far Shore,” which was very brash in its first version and now is much smoother and softer.

The thing with the rerelease is that the rights just reverted to me. I wanted it to be fully mine now, and I have a record label that I released it on. Not to get all Marxist on you, but it’s important to own the means of your production.

I guess, consciously or unconsciously, all art is a response to what is going on in the world and our culture. Maybe the world needs a little bit more softness right now, a little bit more care than it’s getting. I think if your music stays the same, you’re not doing the work right.

I know you scored Kelly Oxford’s new movie, “Pink Skies Ahead,” and just released a new song, “Seeds,” for it. What was it like writing for a movie?

It was super cool. I mean, Kelly is my girlfriend, so I was part of it from the very beginning.

It was a really wild process. Music-making is so insular in a way, it’s usually just me in a room, or me and on other person in a room, max. With moviemaking, it’s literally hundreds of people. I was just a cog in this awesome creative community.

Was it harder to write music for a movie, since you have to follow someone else’s ideas and not write about, say, “Nosferatu?”

I obviously know Kelly very well, and the movie being partially autobiographical gave me a real “in,” because I know what she’s gone through and I know her story. So it made me able to identify with the character more. It’s weird knowing that you’re in love with that character in the future.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO