Yes, Dr. Seuss wrote racist books. He still has things to teach us.

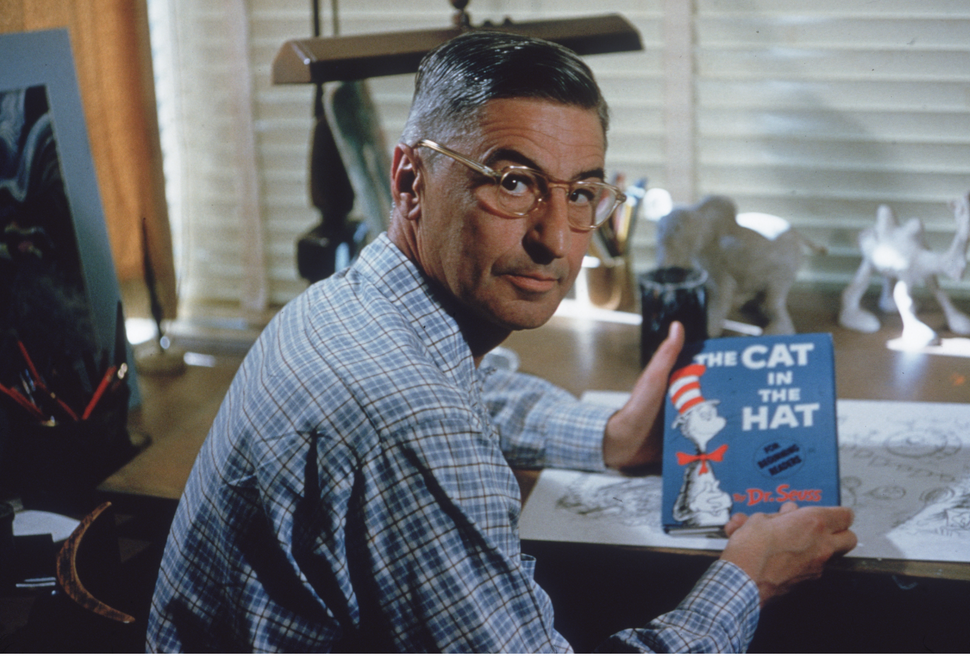

Theodor Seuss Geisel aka Dr. Seuss. Photo by Getty/Gene Lester/Contributer

Update March 2, 2021: This article has been updated to reflect news that six of Dr. Seuss’ books will no longer be published because they “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong.”

My first introduction to fascism was the tin-pot dictator of Sala-ma-Sond.

Yertle the Turtle, the king of a “nice little pond,” clean and quaint with temperate water and plenty of food, was an expansionist. From his lowly rock he determined that, while lord of all he could see, he couldn’t see enough. Like a shell-wearing Nimrod, he built a tower on the backs of his people. Yertle, Dr. Seuss made no secret of the fact, was Hitler.

But he was a sanitized Hitler, one fit for childhood consumption — an allegory to be internalized. Just as the “Butter Battle Book,” with its fanciful arms race, skirted the existential dread of the nuclear age, Yertle never exhibited any thread of ethno-nationalism, offering a simpler lesson about corrupting power and taking advantage of those beneath you. Theodor Seuss Geisel, who would turn 117 on March 2, was not always so subtle or, it turns out, morally lucid.

Geisel, as many young readers learn later in life, was a political cartoonist before he hit it big as a children’s author, operating in the same whimsical style in which he rendered the Cat in the Hat and Horton the elephant. Some of the Dartmouth grad’s cartoons were trenchant and vociferously anti-Nazi when that was not the default position for his Ivy-educated milieu.

A telling example, teasing the Hitler analogue in his later work on “Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories,” is a one-panel of a matron reading to children from a book titled “Adolf the Wolf.”

“… and the wolf chewed up the children and spit out their bones,” the woman tells the saucer-eyed children. “But those were Foreign Children and it really didn’t matter.”

An October 1, 1941 cartoon for PM Magazine. It was one of a number of anti-isolationist pieces Seuss made in the early ’40s. Two months after this was published, America First disbanded after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Image by Wikimedia Commons

The woman’s shirt reads “America First,” for the isolationist organization started by Yale Law School students in 1940. The cartoon, for PM Magazine, was one in a series condemning the America First Committee’s appeasement of — or worse, affinities for — fascists, and notably the only one to invoke children and imply their indoctrination.

But not all of Seuss’ cartoons from that period have landed on the right side of history, nor have all his children’s stories. Racist imagery and attitudes have been rightly challenged in his bibliography in recent years. Last week it was falsely reported that schools in Loudoun County, Virginia, were banning Seuss from “Read Across America,” a literacy day timed to the author’s birthday. The reality, like Seuss’ legacy, is more nuanced.

“Dr. Seuss books have not been banned in Loudoun County Public Schools,” a spokesperson wrote in a statement to the Washington Post, but went on to say that “strong racial undertones” have been revealed by “research in recent years,” prompting the district to provide guidance to their schools to not to make the day an explicit celebration of Seuss. It’s now an opportunity — a welcome one — to elevate other voices in children’s lit.

Fox News, coming off the anti-Cancel Culture CPAC theme, rang alarms that a woke mob was out to get Seuss. “Calling Seuss racist sounds like an Onion headline,” a columnist concluded.

Yet there is solid scholarship on the issue. A February 2019 study found that at as a student at Dartmouth, Seuss drew antisemitic stereotypes of Jews and portrayed Black boxers as gorillas. He didn’t outgrow prejudice after graduating and entering the world of grade school letters. Philip Nel, author of “Was the Cat in the Hat Black?,” has noted how Seuss’ most iconic creation was informed both by minstrelsy and a Black elevator operator at Houghton Mifflin, his onetime publisher. Elsewhere in Seuss’ oeuvre, the racism is overt, playing into common, xenophobic tropes of the time.

“Black and African characters in his books are often depicted as monkeys and apes, while Asian characters are said to be ‘helpers that all wear their eyes at a slant’ from ‘countries no one can spell,’” teacher and parent Charis Granger-Mbugua wrote in a Feb. 28 column for the Atlanta Journal Constitution, citing the beautifully illustrated, if nonessential and certainly offensive, “If I Ran the Zoo.”

“Seuss also wrote racist propaganda against Japanese during World War II,” Granger-Mbugua noted.

He certainly did, and he kept the trend going with his editorial cartoons. You can imagine what his renderings of General Hideki Tojo and Japanese Americans in internment camps looked like. Or look them up. I won’t be linking them here.

This all adds up to a troubling legacy in need of disclaimers — if not the relegation of certain books in Seuss’ canon to the “do not read” pile. Remarkably, we may not have to, at least for some of them.

In an extraordinary step Tuesday, after this article was first published, Dr. Seuss Enterprises, the stewards of the author’s books and characters, announced that six titles, including “If I Ran the Zoo,” “McElligot’s Pool” and “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street” would no longer be published.

“Ceasing sales of these books is only part of our commitment and our broader plan to ensure Dr. Seuss Enterprise’s catalog represents and supports all communities and families,” a statement from the company said.

But does taking these books out of print undo their harm? No. The works continue to pose a problem for Seuss’ standing as a sage of nursery school principles, but they don’t negate him at his best.

While there’s little to commend in the violent and twisted morality of Roald Dahl, the most recent beloved children’s author to face a reckoning, Seuss still offers wonderful values when carefully curated. (I should note, there’s no small privilege in being able to overlook the offending titles, but it’s a winnowing the culture regularly perform when it comes to old — and not so old — art.)

“A person’s a person, no matter how small” is a mantra we must all accept, even if Seuss failed it in his own ways. The parable of the Star-Bellied Sneetches, inspired by Seuss’ (apparently late) disdain for antisemitism, still has much to say about prejudice. “The Lorax” is a lovely if heavy-handed environmental homily. And elsewhere Seuss warns children, in animal terms divorced from race, against being vain or envious (“Gertrude McFuzz”) or prideful (“The Big Brag”). Even though Seuss never had children himself — he didn’t much like them, or people in general, for that matter — he nonetheless instilled in several generations a moral compass that, for the most part, points true north.

While writing this, I am thinking of my 14 month-old niece, whose world is brimming with diverse picture books about dim sum, Malala Yousafzai and the Hindu festival of Holi. She’s being raised to appreciate and understand other cultures, to see them not as foreign, but a part of the human tapestry. Clearly, Dr. Seuss had work to do in this department.

But my niece will probably inherit our own tattered edition of “Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories,” its spine split, its pea-green luster still intact. When she’s old enough to understand the main story’s connection to Hitler’s Anschluss — or perhaps the fate of another, tower-inclined strong man — perhaps we can teach her about Seuss’ racist offerings and tell her why they were pulled from publication.

With any luck, having read Seuss’ other stories, she’ll already know.

PJ Grisar is the Forward’s culture reporter. He can be reached at [email protected].

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO