Authors Unafraid of Kids’ Inner Lives

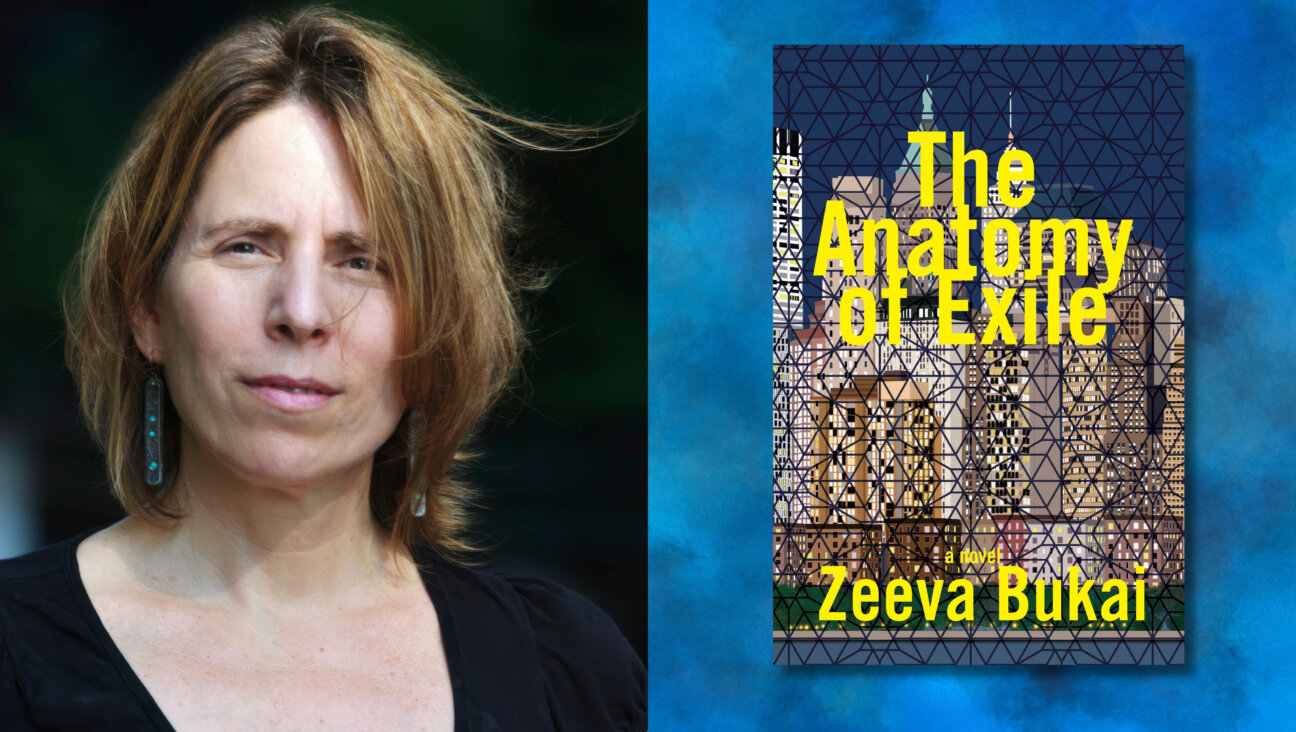

King Matt the First

By Janusz Korczak, Translated by Richard Lourie

Algonquin Books, 352 pages, $13.95.

——

Your children — even those who generally shun books in favor of shoot-’em-up videogames — will truly enjoy “King Matt the First.” Written by Polish physician Janusz Korczak and first published in 1923, the novel stars a pint-sized orphan prince who fights wars, visits foreign kings and wins the loyalty of Bum Drum, ruler of the cannibals. Despite his youth (or maybe because of it), Matt is an admirably fearless hero. When his battle-weary ministers try to resign, he responds, “That’s fine and dandy, but it’s war now and no time to be sick or tired.”

It’s the adults, rather, who suffer from queasy stomachs. “Grown-ups should not read my novel,” Korczak warns in a forward to the book, “because some of the chapters are not very nice.” While the big people tell Matt to do the most boring things and forbid anything that’s fun, this author clearly sides with the kids.

In real life, too, Korczak (née Henryk Goldszmit) devoted himself to children. In addition to writing “King Matt”— which, in Poland, is a classic akin to “Alice in Wonderland” — the physician opened progressive orphanages, trained teachers in what is now called moral education and defended children’s rights. When the Nazis came to power, he refused help from gentile colleagues and friends, and ran an orphanage in the Warsaw Ghetto. On the day of its liquidation, he led, with quiet dignity, 200 children to a Treblinka-bound train.

Korczak’s newly translated book — at once both deliciously absurd and intelligent — delights young readers (as well as pesky parents along for the ride). As king, Matt quickly learns to follow court etiquette, even if that means eating breakfast for no more than 16 minutes and 35 seconds (that’s how long it took his grandfather, the good King Julius the Virtuous), or enduring a freezing throne room (his grandmother, the wise Anna the Pious, decreed no heat for 500 years to honor her lucky escape from a fire). He also learns to blame his temper on ancestor Henryk the Hasty, and picks up some great new epithets — “you sissies, you pantywaists, you dimwits, you jerks, you nincompoops”— when he ventures outside the palace walls.

Still, what makes “King Matt the First” a true classic is its pitch-perfect depiction of Matt’s interior life. The young king is frustrated by his age and by his lack of experience; he misses his parents and longs for friends; he knows that the grown-ups underestimate him. At the same time, he brims with childlike sincerity and candor, as when he coaxes funds from foreign leaders with a note suggesting, “Don’t be piggy.”

By presenting the young king with the same challenges and limitations that real children face, Korczak dares his readers to dream big. Matt’s life in the castle is safe and comfortable, but he is not content to study and play while the country needs him. Instead, he runs off in disguise to join his army, and fights valiantly from the trenches. When he returns, as Matt the Reformer, he gives out chocolate, constructs summer camps and establishes democracy (complete with a special kids’ parliament). His visit to an African ruler — eminently entertaining, if a bit off-color for 2004 — provides some the novel’s best social satire. King Bum Drum proves his loyalty by first throwing Matt into a pit of snakes and then rescuing him, but he is far more faithful than the backstabbing European kings, and he has a pile of gold to boot.

Yet, unlike the plot of so many sappy American stories, Matt doesn’t ride off into the sunset with riches and chocolate. After the grown-ups decide to go back to school and the kids take over the kingdom, chaos ensues and the foreign kings launch another war. Though our hero vows “victory or death” and leads a final charge with the lions from the zoo, this time he does not prevail. The lesson here is that even heroes lose sometimes, and there is no shame in that. When taken prisoner, Matt simply concedes, “That’s how it goes.”

For those who know Korczak’s life story, Matt’s defeat is both painfully and triumphantly prescient. At the end, Matt confronts unanswerable questions: “What would happen to his country?” and “Would he see his father and mother again when the bullets took his life?” But he refuses to despair. The king “had decided to be proud to the end.”

* * *|

Heroism, of course, extends far beyond the fantastical adventures of orphan kings. The historical fiction genre, in particular, brims with examples of courageous young people. Whether confronting Nazi terror or immigrant life in America, Jewish children have persevered in the most difficult of circumstances and have played critical roles in sustaining their families.

Nothing Here but Stones

By Nancy Oswald

Henry Holt and Company, 224 pgs, $16.95.

Life in America is not easy for Emma. Along with other Jews from Kishinev in Tsarist Russia, her family has come to Colorado in the early 1880s with the unorthodox dream of farming. Promised fertile land and comfortable houses, they arrive instead to find a cluster of half-finished shacks in the shadow of desolate, snowy mountains. After an early frost wipes out their crops, Emma’s father and the other men go to work in the mines, and she is left at the mercy of her bossy sister, Adar. Their days are filled with endless chores — fetching water, mending clothes, trying to stretch the last bit of oats — as well as with occasional visits from marauding bears. On top of it all, Emma has outgrown the fancy shoes her mother splurged for back in Kishinev, right before she died. On cold nights, she lies awake listening to the howls of the coyotes, and feels all alone.

Things begin to look up when independent-minded Mindel — Minnie, by her American name — arrives from Denver. She teaches Emma English and helps her nurse a sick horse, Lucky, back to health. And though the other villagers want to sell Lucky, Emma becomes a hero when she uses him to rescue her father. Finally, she realizes, she and her family have made it through their first year on the frontier. Full from her first Passover feast in America, she looks around at her family and friends and knows that she belongs.

Nancy Oswald based her charming tale on the true story of Russian Jews who formed an agricultural colony outside of Cotopaxi, Colo. After surviving several winters in the rugged mountains, most of the settlers moved to Denver, while others became farmers in more fertile parts of the state. Today, the remains of their pioneer experiment still stand on Oswald’s land.

* * *|

The Devil in Vienna

By Doris Orgel

Dial Books, 243 pages, $16.99.

Inge Dornenwald and Lieselotte Vessely have been best friends since they started school. They share everything — secrets, dreams and even the same birthday! Now it is 1938, and everything is changing in Vienna. Inge’s grandfather has applied for a visa to move to America, her classmates are divided between Social Democrats and Nazi sympathizers, and Lieselotte’s father is serving in Hitler’s militia.

Based on Doris Orgel’s own experiences, this captivating novel, originally published in 1978, now appears with a new afterward by the author. “It all happened long ago,” she writes, “but it still matters. I hope readers ask themselves: ‘If someone like Hitler came to power here and now, how would I feel? What would I think and do?’”

Written as a series of diary entries by Inge and letters from Lieselotte, the novel itself invites young readers to ask these questions. The two girls refuse to give up their friendship, even as both most come to terms with the new reality of life in Vienna. Lieselotte is forced to join a Hitler youth group, while Inge’s family desperately searches for a way out of Austria. Though they are forbidden from seeing each other — for Inge, contact with a Nazi household could endanger her entire family — the girls remain loyal. Ultimately, Lieselotte’s uncle, a Catholic priest, writes the false baptism certificate that gives the Dornenwalds safe passage to Yugoslavia.

Orgel’s rich and sensitive novel reveals the capacity of children to wrestle with moral questions, as well as with the power of love and friendship.

Jennifer Siegel is a writer living in New York.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO