The suffrage movement was racist. Where did Jewish women fit in?

A group of nurses wearing white Edwardian clothing, and sashes reading “Votes for Women” and holding pennants while demonstrating in New York in 1913. Image by Ken Florey Suffrage Collection/Gado/Getty Images

Hilary Danailova’s recent cheerfully titled article “Jewish Suffragists, White Dresses and Yellow Roses” in Hadassah Magazine is intriguing. Jewish suffragists? As a woman who is Jewish and Black, whose mother was a refugee from Nazi Austria and father was from Jamaica, I have always known that the overwhelmingly white Protestant leadership and their followers in the suffragette movement would never have been my allies, on any branch of my family. What difference does “Jewish” make when submerged under a racialized identity?

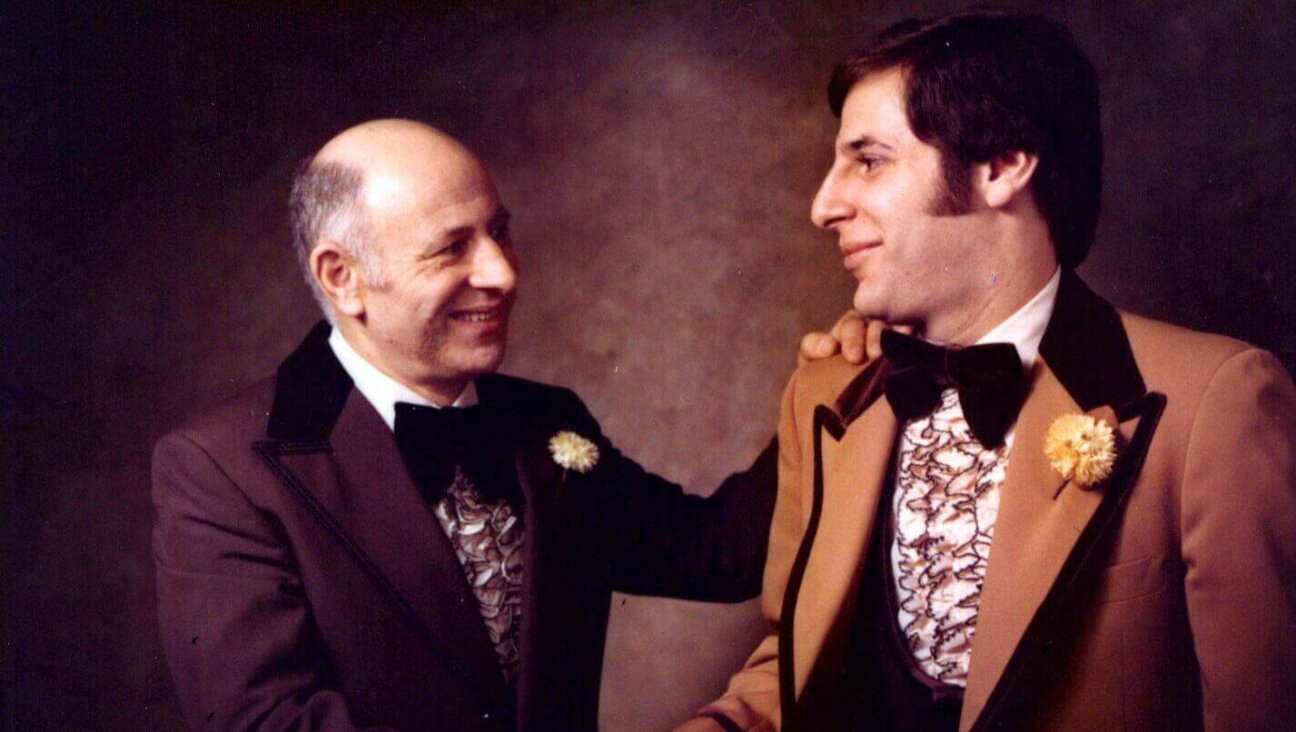

Katya Gibel Mevorach. Image by Courtesy of Katya Gibel Mevorach

The U.S. Civil War ended on April 9, 1865, but ratification of the 14th Amendment, recognizing “people of African nativity or descent” as free citizens, only passed in July 1868. Two years later, and contrary to suffragette expectations, Congress — then composed exclusively of white Christian men — extended the franchise to Black and Indigenous men. Although both Black and white women had been lobbying for the vote, white suffragists’ reaction to the news made clear that their focus on inequality between the sexes had never supplanted their sense of entitlement. High-profile and influential suffragist leaders like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Lucretia Mott reacted with racist outrage. As Stanton infamously bellowed shortly after the Cvil War ended, channeling the sentiments of her constituents, “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ask for the ballot for the Negro and not for the woman.”

Stanton’s outburst was a prelude to arguments to come. When the language of the 15th Amendment left out “sex” and instead codified that the “right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” white women immediately deployed a heavy artillery of racist rhetoric, protesting, in the words of National Women’s Suffrage Association president Anna Howard Shaw, “you have put the ballot in the hands of your black men, thus making them political superiors of white women.”

The bigoted fury of these white Protestant women predictably inhibited coalitions with Black women. Even more so, the competing interests between white women and Black men underlined the differing priorities of Black and white women. Black women’s campaign against both racism and sexism linked political equality and economic opportunity for all citizens. The political acumen of Black suffragists like the journalist and anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells, Mary Church Terrell, first president of the first National Association of Colored Women, and educator Anna J. Cooper offer a stark contrast to the narrow vision of Stanton, Anthony and Mott. As Cooper once chastised white suffragists: “The cause of freedom is not the cause of a race or a sect, a party or a class — it is the cause of humankind, the very birthright of humanity.”

With this context in mind, when I read Danailova’s celebratory title, my immediate reaction was: Where did Jewish women fit in the racist politics of the suffragist movement? And, more importantly, did they participate as Jews, or instead as assimilated white women whose Jewishness was incidental rather than inspirational?

The suffragist movement unfolded on the backdrop of mass immigration from Ireland, Eastern and Southern Europe, as millions of impoverished newcomers were viewed with explicit white Anglo-Saxon Protestant contempt as they crowded urban areas or moved westward. This was also the heyday of scientific racism: New Jewish immigrants, in a marked difference from the earlier immigration of assimilated German Jews, were part of a dramatic influx of peasants, proletarians and artisans socially registered by race as “Hebrews,” with all the corollary eyebrow-raising political implications.

Today, there are Jews who enjoy the privilege of identifying as white until they are reminded of the precariousness of color and class in the face of racist anti-Semitism. Indeed, decades of promoting the idea of Judaism as a religion as a way to counter representations of Jews as a racially distinct people accommodated a very Protestant criteria of assimilation. Yet, paradoxically, it was precisely that 19th-century distinction by white Christians that enabled Jews to win a 1987 Supreme Court appeal recognizing the right to sue for racial discrimination under Civil Rights law (Shaare Tefila Congregation v. Cobb, 481 U.S. 615, 617).

Which returns me to how we should represent suffragettes like Ernestine Rose and Anita Pollitzer, whose biographies were Jewish, but who chose to prioritize their identities as white women. I suggest they can only be scripted into a Jewish version of the suffragette movement by understating the racist environment they chose to inhabit. Recognizing this means recognizing that the white Christian men in Congress who ratified the 19th amendment needed the vote of white Protestant wives, sisters and daughters to seriously offset the political leverage of undesirable male immigrants, including Jews, who met the ambiguous prerequisite for naturalization of “free white person.” While anti-Semitism would remain a significant thread in American social attitudes, anti-Black racism would fester in the center of American politics.

How do we — invoking the collective self from the Passover Haggadah — think about the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment? Perhaps this election year offers an opportunity to think, very deliberately, about how racism and political activism sometimes serve to Americanize Jewish history — and in the process, overshadow Jewish diversity and undervalue activism built explicitly on linking social and political justice to Jewish sensibility.

Katya Gibel Mevorach, a dual American and Israeli citizen, is Professor in Anthropology and American Studies at Grinnell College. She is the author, under the name Katya Gibel Azoulay, of “Black, Jewish and Interracial: It’s Not the Color of Your Skin but the Race of Your Kin, and Other Myths of Identity”

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO