How Refugee Artists Processed Their Displacement During The Nazis’ March Toward War

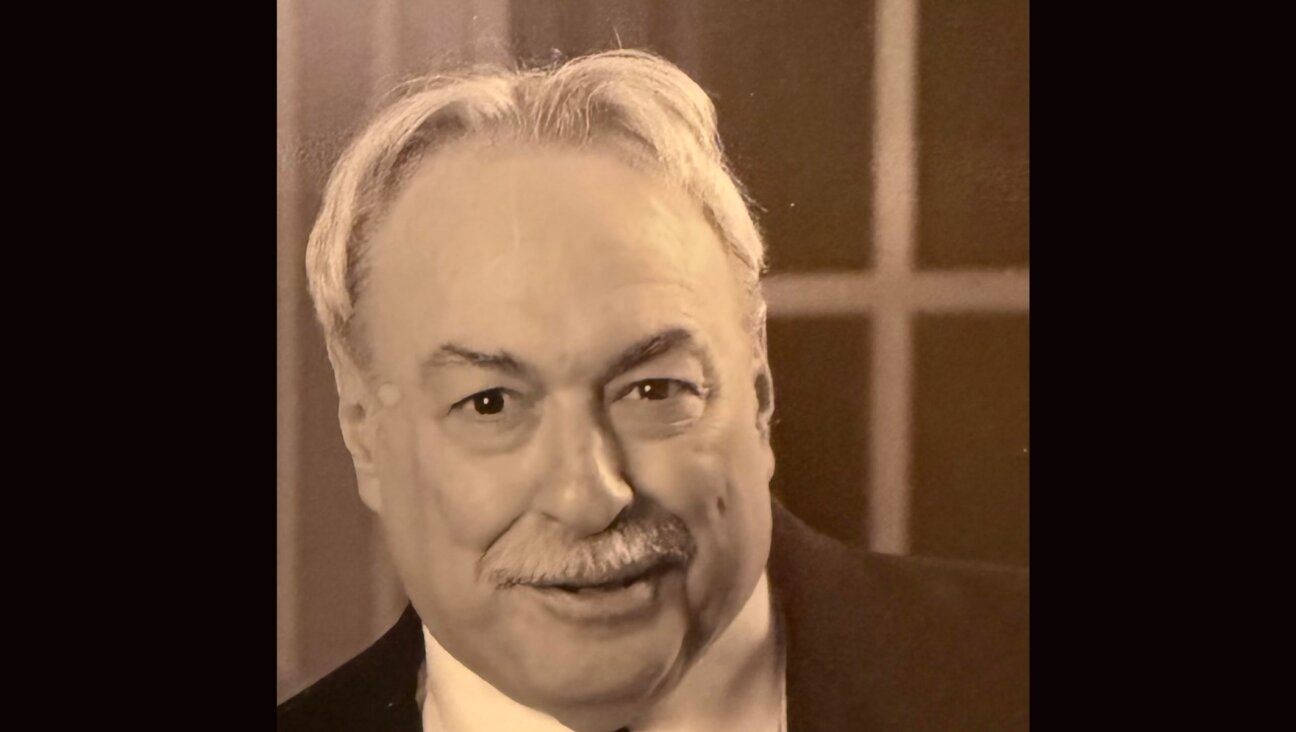

Nora Kronstein-Rosen, “Refugees.” Image by Courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute

In the late 1930s, as the global threat of Nazism accelerated, a number of Jewish artists fled en masse from Germany and Austria, seeking safe harbor wherever they could.

“The Art of Exile: Paintings by German-Jewish Refugees,” an exhibit by The Leo Baeck Institute at the Center for Jewish History that began in June, tells the story of 11 refugee artists through work they completed during their time in exile during the war and, in some instances, decades later. The exhibit speaks vividly to the past while evoking contemporary concerns about the worldwide refugee crisis.

“This is the story of migration — in this case forced migration — adaptation and assimilation, but also maintaining identity,” said William Weitzer, executive director of the Leo Baeck Institute. Weitzer and the exhibit’s curator, Magdalena M. Wrobel, decided to feature refugee artists as a follow up to their 2018 effort, the 1938Projekt, an online calendar of pivotal events in the year before the Nazi annexation of Austria.

“In this exhibit we try to ask what happens to artists and their creativity once they become refugees,” Wrobel said. “We take very different stories and very different geographical destinations. You will see paintings from Asia, North America, South America and also from Europe.”

Pulled from the Baeck’s collection, the paintings — and one mosaic piece — on view reveal a diversity of experiences in a variety of styles. While not all of the artists on view met with the same levels of success, and some of the pieces are not particularly memorable or refined, taken together the objects indicate a human need to document a life uprooted by strife.

David Ludwig Bloch, “Shanghai, Street Scene,” 1949 Image by Courtesy of Leo Baeck Institute

David Ludwig Bloch’s simple watercolor street scene of Shanghai might not, under normal circumstances, stop a viewer in her tracks. But given the personal history of the deaf, Munich-born Bloch, one of the 20,000-odd German Jews to escape to the Chinese municipality, the work attains greater significance. Bloch, before arriving in China, was detained in Dachau in the aftermath of Kristallnacht, only managing to escape through the financial assistance of an American relative.

Next to Bloch’s work is that of Julius Wolfgang Schülein, who became a world traveler after fleeing Munich. Schülein is represented by an expressionist landscape dotted with horses. On its face, the painting doesn’t indicate a specific locality, registering as a generic hillscape. It was, in fact, a view of the British Virgin Islands, one of the many places Schülein came to call home. When taking account of Schülein’s original homeland, the prominent mountains assume a new meaning, echoing the terrain of his native Bavaria.

Julius Wolfgang Schülein, “Landscape in the Virgin Islands” Image by Courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute

The Austrian painter Nora Kronstein-Rosen, who fled to Lichtenstein and then Switzerland with her sister, the feminist author Gerda Lerner, managed to continue her education, first in a Swiss boarding school and later in Zurich, where she studied under Bauhaus artist Johannes Itten. Despite these evident advantages, Kronstein-Rosen lost her other sister, Margit, to the Holocaust and had to leave her mother behind in Lichtenstein, where she died. Kronstein-Rosen, who later lived in the United States, London and Israel, appears to have been deeply affected by her separation from her family, as seen in her work “Refugees.” One of the most arresting and skillful pieces in the exhibition, the painting shows a mother cradling her infant child in a liminal landscape, appearing to await admission to another land.

Nora Kronstein-Rosen, “Refugees.” Image by Courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute

The one non-painted piece in the exhibit is also the strongest testament to the human need to create, even in extreme conditions. Simon Schames cobbled together “The Tear” from found materials during his imprisonment in an alien internment camp near Liverpool. English authorities arrested Schames after he arrived in London from Holland in 1939, viewing him as a security threat owing to his German origins. Schames, who came from an Orthodox background and regularly invoked religious themes, continued to create art during his internment, working with bits of wood, glass, stones and even debris left by German bombings on the camp. His collage displayed at the Baeck, which depicts a face contorted in despair, reveals the pain of his conditions. One wonders if it is not, in fact, a self-portrait.

Samson Schames, “The Tear.” Image by Courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute

Of the thousands of German and Austrian refugees who left home before the outbreak of World War II, some managed to keep up the momentum of their careers in new surroundings. Eugen Spiro, an established portraitist who left Germany for France in 1935 at the age of 61, established the Union Des Artistes Libres, a federation of his fellow exiled German artists in Paris. He had to relocate once more in 1940 after the Nazi occupation of France, but found another community of German exiles in the United States. He painted some of them, including Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann. While the Baeck has a number of Spiro’s portraits as holdings, it selected a landscape for inclusion in “The Art of Exile:” A view of Washington Square Park — a calm scene suggesting a man at peace in his new milieu.

Eugen Spiro, “Washington Square.” Image by Courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute

These pieces, from the religious and existential pain of Schames to the secular peace of Spiro, signal the many ways in which the experience of exile can inform artists’ work. But for all that the artists persevered in their craft in the face of disruption, it is inestimable how many had their creativity dampened by the trauma of their lost homeland.

The Baeck exhibit ends with an empty frame, signifying the art that, after World War II, couldn’t be recovered — or was never made. It also alludes to the countless more works the world is deprived of in the upheaval of the current refugee crisis.

“There are still about 70 million refugees worldwide,” Wrobel said, “and there are artists among that number. Some of them are perhaps deprived of the ability to be creative.”

PJ Grisar is the Forward’s culture fellow. He can be reached at [email protected]

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO