How Robert Caro gets it done

The master biographer on the obsessions that drive him, whether he believes power always corrupts, and his love for Jackie Robinson

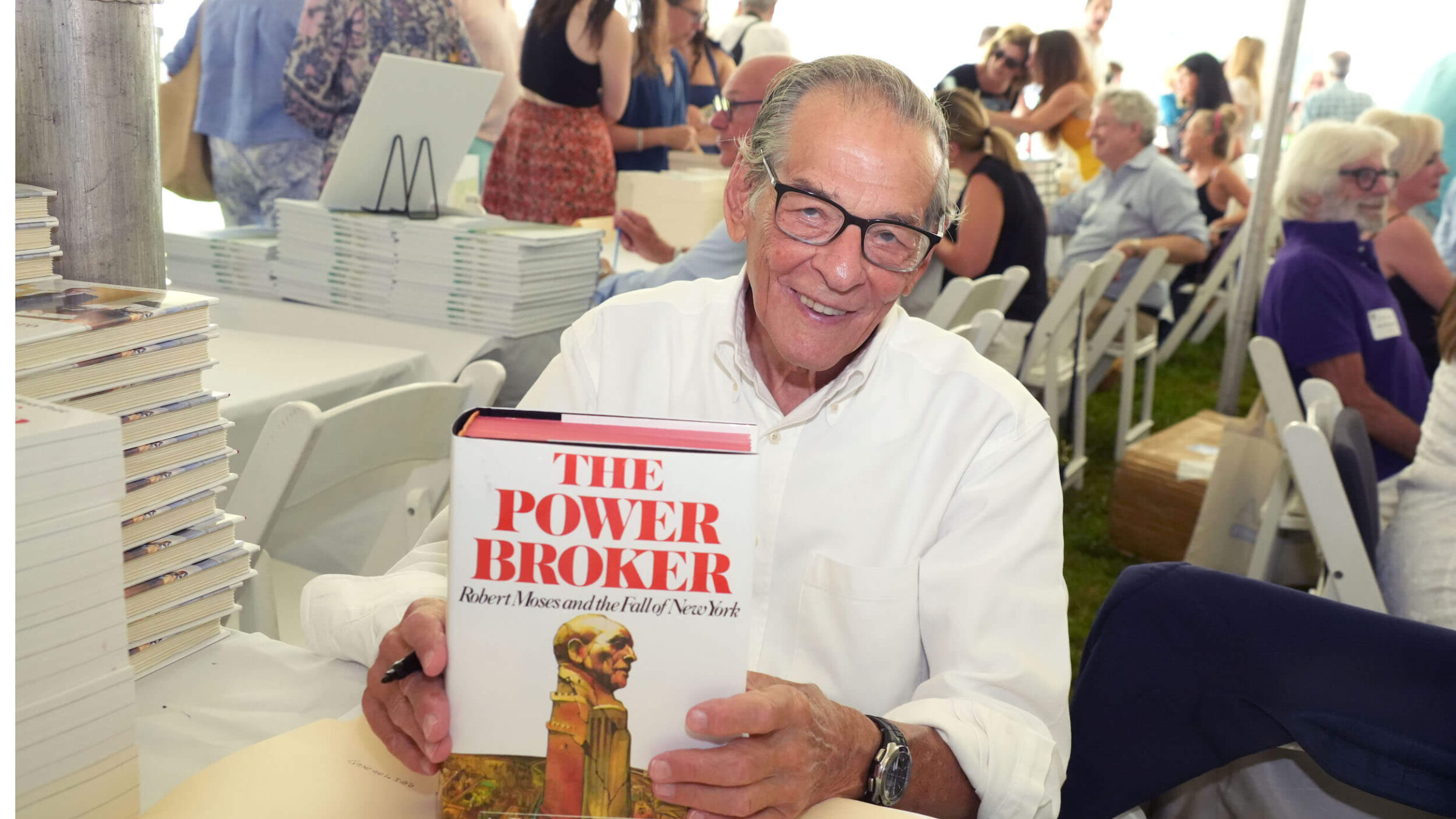

Robert Caro, pictured at East Hampton Library’s 20th Annual Authors Night Benefit on Aug. 10. Photo by Sonia Moskowitz/Getty Images

Editor’s note: This story, originally published on Apr. 16, 2019 — when Robert Caro was 83 — has been republished in honor of Caro’s 89th birthday.

If, while interviewing Robert Caro, you mention that you’re related to someone knowledgeable about a subject he is currently researching, he will insist you ask that they recommend some top-notch sources. The interview will continue, and at its end, after he thanks you for stopping by, he will remind you that it would be really great if your mother took just a minute to share the best books she’s read about Medicare. In case you missed it, here’s his office number. Call and tell him what she says.

Adherents of Caro, whose biographies of Robert Moses and Lyndon B. Johnson have won cultish admiration across the country — name another biographer whose fans lustily insist that he “take me to the FDR Drive and run me over” — will not be surprised to learn that he is working on his books all the time. Yes, even when he is supposed to be engaged in a somewhat different kind of work, specifically that of promoting his semi-memoir Working.

That’s the first thing to know about Caro, who is 89. The second thing is neatly suggested by a note at the end of Caro’s first book, The Power Broker, the biography of Moses that won him the first of his two Pulitzer Prizes. “From its inception, Robert Moses did his best to try to keep this book from being written — as he had done, successfully, with so many previous, stillborn, biographies,” Caro writes.

Caro clearly won that battle; in “Working,” a collection of essays about research and writing, he lays out how he did so. Knowing that he’d be met with silence from Moses’s inner circle, and likely those “in the next circle or two, also,” Caro went first to potential sources who had useful links to New York City’s so-called “Master Builder,” but weren’t close enough to warrant gag orders from his camp. Some of those outer-ring people talked. Then more. After two years, so did Moses. One of Moses’s aides, Caro writes in “Working,” said that Moses, “learning of my stubbornness despite his strictures, had concluded that at last someone had come along who was going to write the book whether he cooperated or not.”

Caro insists that Moses and Johnson, as men, aren’t really the primary focus of the books he’s devoted to their lives. The main subject, in both cases, is a question: How does power work? Caro used Moses to examine the use and impact of power on a local level. With Johnson, Caro is in the process of expanding that inquiry to apply to a country. (So far, The Years of Lyndon Johnson numbers four volumes, with a fifth and final installment in the works.) But Caro’s books themselves form a portrait of a third kind of power: That, for lack of a less clichéd phrase, of narrative.

Moses understood that power. That’s why, in the end, he chose to speak to Caro. Johnson understood that power, employing it to create both his most remarkable legislative achievements and the most deceptive public myths about himself. Caro, who might be said to be innately drawn toward that power, has turned its proper application into a goal in and of itself. “I don’t believe that power always corrupts,” he told me, sitting in his sparsely furnished Upper West Side office one morning in March, wearing a mulberry sweater over a blue collared shirt. “I think power can also cleanse.”

He was talking about Al Smith, the pioneering New York governor about whom he wishes he had time to write. (With the last Johnson volume and a full-scale memoir both on the way — Working is just a preview — he knows such time is unlikely to manifest.) But the idea that power can be restorative, rather than exclusively corrosive, reflects back on him, as well. In his work, Caro has reshaped crucial stories of America’s national purpose and identity, whether they concern the legitimacy of Johnson’s 1948 election to the Senate or the political impact of Jackie Robinson’s success as the first black Major League Baseball player. “I’m really trying to show America, from about 1920 up through the 1960s,” Caro said. By scrupulously investigating and telling that story, Caro is changing it.

That is power. In Working, Caro shows just how he got it.

Woe to those who’d like to follow in his precise footsteps. The game, as Caro tells it, has to do almost exclusively with inborn character. (I used the phrase “the tyranny of character,” which he returned to several times. “I’m gonna try to forget it,” he said, ruefully. “It’s too unpleasant.”) Character, that is, and an exceptionally supportive spouse-slash–research partner, in Caro’s case the writer Ina Caro, author of The Road from the Past. Caro is famous for the intensity of his research process — for his first book on Johnson, The Path to Power, he relocated himself and Ina from New York City to Texas’s remote Hill Country for three years — but takes no credit for his internal drive. “Looking back on my life I can see that it’s not really something I have had much choice about,” he writes in Working, “in fact, that it was not something about which, really, I had any choice at all.”

It’s a life’s work to admit that you just are the way you are. How did Caro, a master at parsing personality, come to know his own? “The great figure of my growing up was Jackie Robinson,” he said. He’s a storyteller, so he knows how to take his time; if you have the good fortune to be listening to him, you learn — happily — to be patient. “I went to Horace Mann,” he said, which “ended earlier than the public schools in Manhattan. A whole group of us, we’d take the subway — as I remember, it took an hour and a half each way to get to Ebbets Field and back — and there was nobody there [for] the day games. The ushers would let us go down to the front row as early as the second or third inning. We would always go to the third baseline, because we wanted to watch Jackie Robinson dancing on third.”

Fast forward some decades, and Caro was writing Master of the Senate, which chronicles Johnson’s work ensuring the passage of the oft-forgotten 1957 Civil Rights Act, the first such legislation since Reconstruction. (The act, which established the Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department, had a limited impact but laid meaningful groundwork for the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act, which Johnson would oversee as president.) “I was writing about civil rights and trying to show what was happening in the 50s,” he said. “I found myself writing about how America’s consciousness was rising, and it was suddenly impossible to ignore what we were doing to black people.”

He picked up a copy of Master of the Senate, the third Johnson volume, and read aloud: “When you saw the bat held high and then whipping through the ball, when you saw the speed on the base paths, and when you saw the dignity with which Jack Roosevelt Robinson held himself in the face of the curses and the scorn and runners coming into second base with their spikes high, you had to think at least a little about America’s shattered promises.”

Caro looked at me from across a broad wooden desk — one of two in his office, pushed together at right angles — and chuckled. That “you” in the passage? “I don’t say it’s me, but this is about me.”

Ebbets Field was the home of the Brooklyn Dodgers. In the late 1940s and early 50s, when Caro attended games, before the team moved to Los Angeles and the stadium was demolished and replaced by an enormous apartment block, he was traveling to a neighborhood that was in many ways recognizable. He came from a Jewish family on the Upper West Side, and Flatbush, where Ebbets Field was located, was a predominantly Jewish area. Caro writes frequently of his insistence on asking his interview subjects to describe what they saw at a particular time, often to their frustration. It’s powerful to imagine what Caro, a Jewish teenager in a Jewish neighborhood, saw when he looked at Jackie Robinson: Someone who forced a reconsideration of the norm.

It was a kernel. “I didn’t really realize why he was such a hero to me until I was writing ‘Master of the Senate,’” Caro said.

All of Caro’s stories about the times when he’s become most fanatical about his work have to do with covering inequality. That subject is central to his books. “I believe if you want to talk about political power, what it really means, you have to not just write about the powerless, but write about them so that people empathize with them,” he said. He cites the same examples of his research, over and over, to demonstrate the importance of that task.

Take the New York neighborhood of East Tremont, which Robert Moses cleaved in half as he built the Cross-Bronx Expressway, reducing it from a low-income but thriving area with strong civic ties to a slum. The former residents of the neighborhood lived the rest of their lives, Caro writes in Working, with “a sense of profound, irremediable loss, a sense that they had lost something — physical closeness to family, to friends, to stores where the owners knew you, to synagogues where the rabbi had said Kaddish for your parents (and perhaps even your grandparents) as he would one day say Kaddish for you, to the crowded benches on Southern Boulevard where your children played baseball while you played chess: a feeling of togetherness, a sense of community that was very precious, and that they knew they would never find again.” The new residents were forced by economic desperation to accept staggeringly poor living conditions that only grew worse over time. Caro spent weeks knocking on apartment doors in the neighborhood, encountering extreme misery in the process. “I had never, in my sheltered middle-class life, descended so deeply into the realms of despair,” he writes.

Another example he brings up frequently is the condition of black people in the South before the Civil Rights Movement, and specifically, a series of conversations he had with a black Alabama couple named Margaret and David Frost. In 1957, Margaret Frost had testified in a hearing before the United States Commission on Civil Rights about the humiliation and injustice she’d faced while trying to register to vote in Alabama. Decades later, after studying that hearing, Caro called her. They spoke several times, and she eventually directed him to her husband, David. “This whole other thing opens up to you,” Caro said. (He often refers to himself in the second person.) David Frost had also tried to register to vote, and been successful. Shortly after, Caro said, “people come by and shoot the lights out on his porch, and he wants to call the police, and then he looks out and sees it’s a police car that [fired the] shots. That’s like the Jews in Germany. There’s no place to turn. There’s no one to help you.”

That’s a story Caro has told many times. He tells it in “Master of the Senate.” He tells it in Working. But he’s still thinking about it. When he finished telling me, he began to speak more slowly, thinking each word through. “You wouldn’t be telling this story thoroughly or honestly, it wouldn’t be honest to tell it unless you showed the full extent of what happened to these people because they had no power,” he said. “Because they didn’t have the power of the vote.”

From Jackie Robinson to East Tremont to the Frosts, the through line is clear. The narrative of inequality in this country, in all its insidious and underexamined detail, stands at the core of Caro’s work. It’s a story he could only gain the freedom to tell by framing it in the much more irresistible subject of power, and men who used it their own advantage. Speaking about the appeal of Al Smith, the figure whom he will likely never get to fully study, he focused on how Smith rose to power in the early 1900s by becoming part of New York’s corrupt Democratic political machine, then known as Tammany Hall, then flouted that machine as governor.

“When you’re climbing to get power you have to conceal what you really want to do,” Caro said. “But once you get the power,” he said, “then you can do what you always wanted to.”

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO