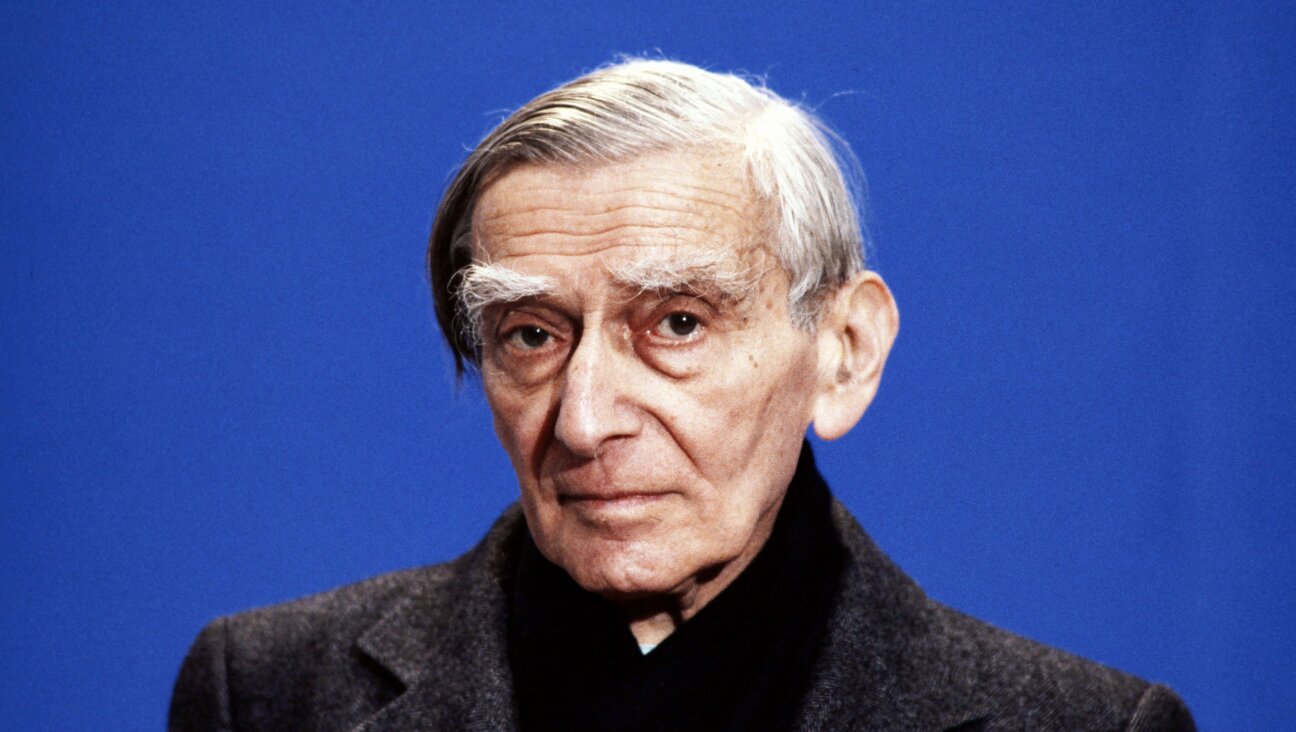

Q & A: Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs Biographer, Discusses New Book On Da Vinci

Image by Mike Windle/Getty Images

Did it ever occur to you, upon encountering a woodpecker, to wonder about the structure of its tongue?

If so, congratulations: You may be the next Leonard da Vinci.

Well, only if you’re also curious about some other things: How to divert a river, say, or walk on ice, or measure the sun, or turn a chariot into an unstoppable war machine. Or paint a realistic human mouth, or invent a helicopter, or invent new methods of painting perspective.

Image by Courtesy of Simon & Schuster

The range, flexibility and inexhaustibility of da Vinci’s creativity take the spotlight in Walter Isaacson’s new biography of the masterful painter and polymathic – if impractical – inventor. Isaacson, previously the CEO of the Aspen Institute, editor of Time Magazine, and chairman of CNN, has penned biographies of a string of notable men: including Steve Jobs, Alfred Einstein, Henry Kissinger and Benjamin Franklin.

We spoke on the phone to discuss “Leonardo da Vinci,” Isaacson’s interests as a biographer, and the mechanics of creativity. Read excerpts of that conversation, below.

Talya Zax: In the introduction, you say that da Vinci’s genius was notably human, not divine. In studying his life and work, how did you come to that determination?

Walter Isaacson: What I first began to appreciate was that he was lucky to be born out of wedlock because he didn’t get sent to a traditional classical school, a university. He was mostly self-taught. That taught him to be a disciple of experiments and experience. That’s the beginning of the scientific revolution: Testing out received wisdom. I also realized, as I read through his notebooks, that he made math mistakes, he did not speak Latin very well, but every day he would make a list of the things he wanted to learn. He was born right when Gutenberg began printing books. So we see 400 books that he got, and maybe 1,000 experiments that he did. That ability to teach himself and to push himself to be more curious, more observant, more open to mystery was the sort of thing that made him more accessible.

A theme in the book is da Vinci’s ability to, in your words, “apply imagination to intellect.” What did you find to be the particular challenges, and pleasures, of trying to capture that quality?

One of the challenges with Leonardo is that his imagination runs wild sometimes. He invents flying machines that don’t fly. He works on rivers that he’s unable to divert. He designs monuments that never get built, writes treatises that he never finishes for publication. He doesn’t follow through on everything. I began to appreciate that for him, the conception of a great idea would cause the thrill, and then he would take his time, sometime years, in polishing it and executing it. He didn’t do it simply to please a patron.

Previous authors have said that Leonardo wasted too much time studying anatomy or geology or math. But I began to appreciate how an understanding of how we fit in to creation, and all the beauties of the cosmos, was key to making him a genius as an artist. I say in the book that in face of these criticisms, the “Mona Lisa” answers with a smile, because the smile [of] the “Mona Lisa” smile took him 16 years to perfect. It involved dissecting human faces to figure out every muscle and every nerve, it involved dissecting the human eye to see how the eye sees deeply, dealing with ways to make the corner of the lips, in sharp detail, not look like she’s smiling, but the shadows do look like she’s smiling, so the smile flickers on and off depending on how you’re looking at her.

In the book’s conclusion, you review the lessons that contemporary readers might take from da Vinci’s life. As a biographer, to what extent do you feel you need to write to contemporary interests? Was that calculation different in this biography than it has been in past biographies you’ve written?

I’ve written a series of biographies about creativity and how to achieve it. Franklin, Einstein, Steve Jobs, and now Leonardo. Leonardo is the culminating book in that series. He was the most creative genius in history. I wanted to distill some of the wisdom that might be useful to people not just from the Leonardo book, but from some of my other books as well. I just thought it might be useful to a reader. Did writing about him change your personal understanding of genius?

I realized from Leonardo that just thinking about what I wanted to learn and how to be more observant changed the way I walk around town. I now try to see, when light hits a curved object, how the shadows are formed, or when water falls into a bowl, how the eddies are formed. When somebody begins to smile I try to fathom her inner emotions more carefully, the way Leonardo did with the “Mona Lisa.” It’s not like trying to be Einstein and figure out the equations of general relativity. These are everyday things; we can appreciate the incident beauties of creation better.

How did you find yourself focused on biographies of great creative people? Do you have any more you’d like to write, and if not, what’s next?

It began by happenstance. I wanted to write about Henry Kissinger, because I was interested in the Vietnam period. After Kissinger I became interested in realism in American foreign policy and decided to take on Ben Franklin. That led me to want to do Einstein, because of what a great scientist Ben Franklin was; part of that realization was that the most creative people are people who love both the sciences and the humanities. That’s when I developed the theme that I continued to explore, which is the connection between art and science. For Steve Jobs, the guiding star was that beauty mattered and we should connect art and science. That’s why Steve Jobs loved Leonardo, and that’s why I realized that Leonardo would be the ultimate in this description of how to be truly creative. You have to see patterns across disciplines.

I’m moving on to teach history at Tulane, become a good citizen of my hometown of New Orleans. I might write a book about race and religion and class and music in New Orleans in the 1890s, but it’s not going to be the same as tackling a creative genius like I have in my past four books.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO