EXCLUSIVE: That Time Adolf Hitler Had A Jewish Neighbor

Edgar Feuchtwanger as a boy Image by Courtesy of the Feuchtwanger Family

The English Jewish historian Edgar Joseph Feuchtwanger was born in Munich in 1924. In 1929, Adolf Hitler moved into an apartment on Grillparzerstrasse across the street from Feuchtwanger’s family. “Hitler, My Neighbor: Memories of a Jewish Childhood, 1929-1939” recounts how as a youngster, Feuchtwanger witnessed the rise of Hitler. Feuchtwanger’s previous, much-respected books are about Benjamin Disraeli,; Otto von Bismarck; and Queen Victoria, among others.

Recently Feuchtwanger, an emeritus professor at the University of Southampton, spoke from his home in a village near Winchester in southern England with The Forward’s Benjamin Ivry about his family, his books, and his lethal neighbor.

“Hitler, My Neighbor” has drawn much media attention to you as a passive eyewitness to history, whereas recognition of your accomplished career as an historian has been limited to specialized journals. Is this because the average person can identity more with an inactive bystander than an energetic researcher?

Surely the position is that there are not many people around now who have seen Hitler at close quarters, face to face. Who can say that now? That did happen to me.

In “Hitler, My Neighbor,” your mother complains that she cannot get milk delivered because the dairy company was sending extra bottles to Hitler, who monopolized the supply. According to the memorandum “Recollections of Adolf Hitler” by the journalist Edward Deuss, Hitler’s meals on speaking tours included a single glass of milk. Voracious he surely was to conquer other countries, but was Hitler really a milk-guzzler? Did he bathe in it?

I don’t know. Presumably Hitler had a household and there were other people there, including his niece who later committed suicide. A household needs milk, it’s a natural thing to have, so it’s not necessary that Hitler consumed it all himself. Others in the neighborhood were told that there was no milk left because it had all been delivered to Herr Hitler’s home.

Pages from Edgar’s Gebeleschule exercise book, 1934 Image by Courtesy of the Feuchtwanger family

Until 1935, you were in a school where the teacher was an ardent Nazi who assigned the class to draw swastikas. What kept you from rejecting Judaism and deciding that you wanted to convert?

She was called Fraulein Weikel, wasn’t she? I listened to everything she said and did everything she told me, because that is what one was supposed to do when teachers gave instructions. But that did not mean I accepted the message of her lessons. I was very glad I didn’t have to go into the Hitler Youth. I didn’t like that at all and didn’t want to go into that. I wasn’t sorry to be Jewish, no.

Since historians may find evidence anywhere, in the Mel Brooks film “The Producers” (1968) the Nazi Franz Liebekind claims: “Hitler was better looking than Churchill. He was a better dresser than Churchill. He had more hair!” Based on your personal observations, was this so?

I don’t know. Hitler was distinctive looking, wasn’t he? The little mustache he had made him a very recognizable person, but not in a good way. One could always see him. He would wear a white mackintosh, not very stylish, and a trilby hat.

“The New York Times” describes you as probably the “last German Jew alive who grew up within arm’s reach of Hitler and observed him day to day, if only in fleeting glimpses.” Has anyone accused you of being remiss for not leading an “Emil and the Detectives”-type revolt with your schoolmates to overthrow Der Führer?

I think that’s a highly unrealistic scenario. I couldn’t have done that. It wouldn’t have succeeded.

Your father, the author and publisher Ludwig Feuchtwanger (1885-1947), had an extensive correspondence with his author, the German political theorist Carl Schmitt. Was there any hint that Schmitt would join the Nazi Party in 1933, call himself a radical anti-Semite, and demand in 1936 that for German law be cleansed of the “Jewish spirit (jüdischem Geist),” publications by Jewish scientists should be marked with a small warning symbol?

Well, I don’t know. We still got a letter from him from, I think, November 1933 where he was still signing himself to my father as “Your own Carl Schmitt,” so he hadn’t changed. And only months later he wrote these notorious things. He came to visit my father all the time, and I was told a famous professor was coming and I was to come in with my nanny and then leave again. I remember Carl Schmitt leaning against the piano in our home, a piano which I still have here where I’m living. Schmitt saw things changing and so he switched. Not a very nice thing to do, but that is what he did. As the saying goes, he heard the grass growing with the sound of thunder.

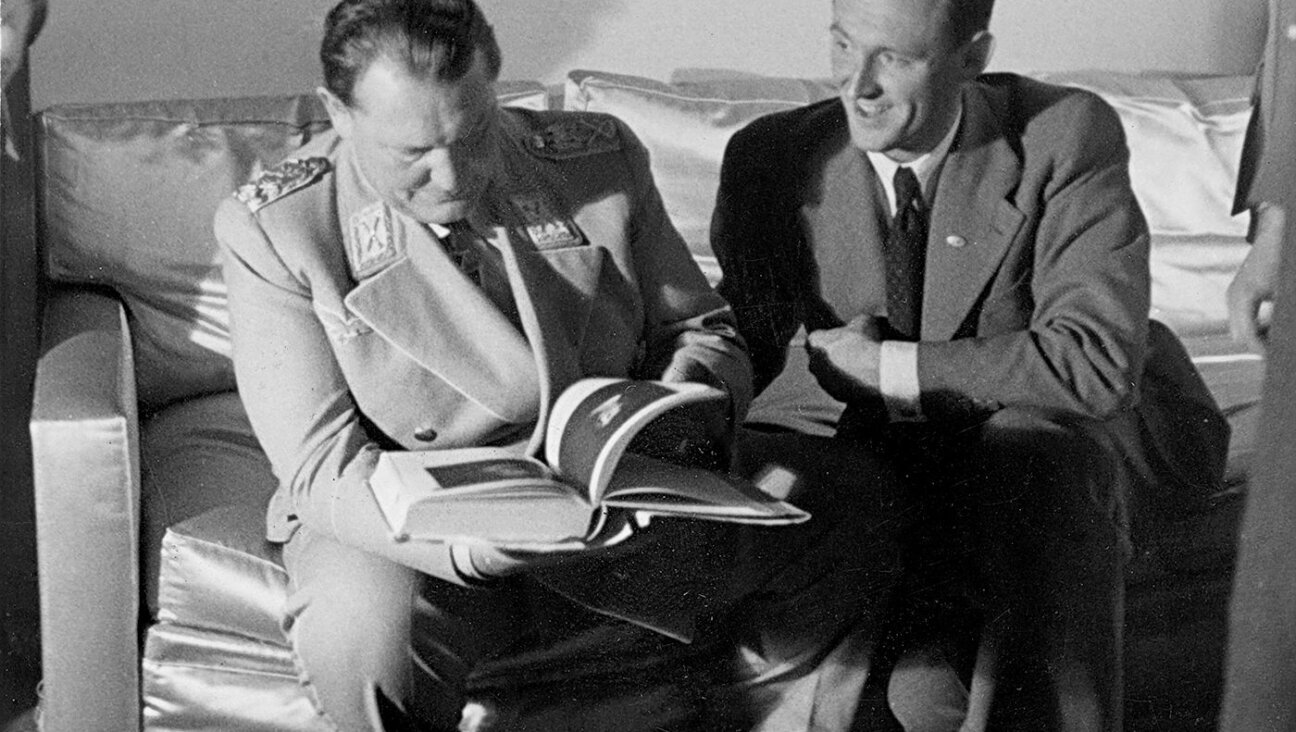

Feuchtwanger (right) with co-author Bertil Scali. Image by The Other Press

Werner Sombart, another of your father’s authors, was an economist and sociologist who in 1934 published “German Socialism,” claiming that the “new spirit” of Nazism was beginning to “rule mankind” and that the antithesis of the German spirit is the Jewish or capitalistic spirit. According to Sombart, destroying this spirit was the “chief task” of the German people and Nazism. How did this serious thinker who had known and worked with your father become racist so quickly?

Well I suppose they saw which way the wind was blowing and suddenly this was the prevailing thing. After all, Hitler was all-powerful, he was Der Führer.

Your father’s brother, the novelist Lion Feuchtwanger (1884 –1958) wrote the novel “Success” (1930), about the rise and fall of the Nazi Party, which he considered already passé.

He was talking about the Beer Hall Putsch and the failure of all that, but my uncle had a fairly clear perception that [Nazism] was a dangerous thing and had to be fought tooth and nail. And for that, I think my uncle deserves a fair bit of credit. I think he saw it all more clearly than most people did, and that’s one of the reasons he didn’t go against Stalin because he saw that Stalin was one of the people who were going to be required to defeat Hitler and that turned out to be the case. My father went to Berlin around 1929 -1930 and my uncle read him passages from “Success” and my father, who was a more emollient man, said, “That’s going to cause us a lot of trouble.”

In 1955, your uncle published “The Jewess of Toledo” defending the idea of a Jewish state as a lasting refuge. Could this be his work with the most enduring message?

I couldn’t say. [Lion Feuchtwanger] is rather off the literary radar in the Anglo-Saxon world. He is no longer very well known. He is still read in Germany, but not in the Anglo Saxon world.

Lion Feuchtwanger’s most famous novel remains “Jew Süss” (1925) about Joseph Süß Oppenheimer (c.1698 –1738) a German Jewish banker and court Jew for Duke Karl Alexander of Württemberg in Stuttgart. Oppenheimer was hanged after being convicted of fraud and treason. Given his fate, while predictions are risky in history, would you suspect that court Jews today, such as those serving in the White House, might be well advised to watch their step?

(Laughs) Good question. I don’t know. The whole present situation, Trump and so on, I know nothing about. Is electing Trump somewhat like electing Hitler, would you say?

In an interview in 2014, you joked that the Chancellor of Germany, Angela Merkel, is “blissfully without charisma… One’s had enough charismatic personalities in German history to last for good and all.” Should all countries beware charismatic leaders?

Well, I suppose so, yes, that’s the problem, isn’t it? The people on the ground, the electorate, are not always sufficiently wary and let themselves be taken in. Maybe people are too gullible. One must not overestimate the discernment of the men and women on the ground. Politics is at the edge of their lives; they’ve got other things to think about that are more important to them than ideas. It’s a mistake to eulogize the people, the ordinary man and woman. What they can do is limited; they’ve got their daily lives to cope with.

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO