How The Klezmatics Changed Music — and My Life

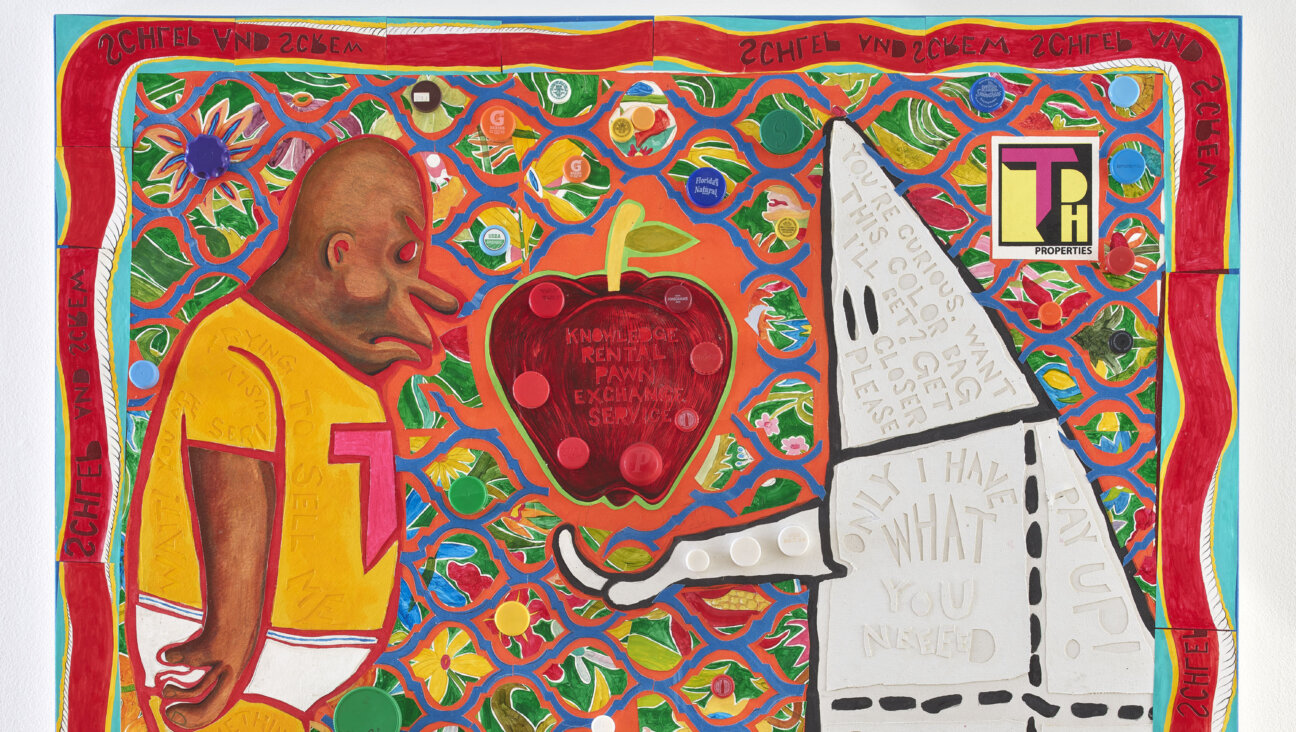

The Klezmatics Image by Adrian Buckmaster

It’s only a slight exaggeration to say the Klezmatics changed my life.

Somehow I made my way to the Knitting Factory nightclub in downtown Manhattan in April 1997 to see the album release concert for the Klezmatics’ album “Possessed.” I was there in part as a music critic of 15 years’ standing, and partly out of personal curiosity about this music and this scene that I was just beginning to discover. The club was filled with all flavor of fans — refugees from the 1970s Reform Jewish folk-music movement; jazz hounds; traditional Jewish men dancing with each other with tsitsit flying; post-punks; radical Jews; renewal Jews; and what looked like a busload of young Deadheads by way of jam-band Phish who got off at the wrong stop and wound up at the Knit (I know this because I interviewed some of them).

The nearly psychedelic variety of sounds the band was pumping out onstage even outdid the reckless menagerie of bodies and sweat on the dance floor. My critical distance went out the window as my heart did backflips and my soul connected deeply with the melodies that echoed the cantorial singing of my grandfather, and I found myself not so much dancing but shuckling as I became one with the slivovitz-fueled crowd. Something was happening here, but I didn’t know what it was. It became readily apparent that my mission — both professional and personal — was to figure that out.

The next step was both easy and difficult. At the time, resources for learning about klezmer were few and scattered all over the place. Individual stories were buried in the liner notes of the 300 or so albums I discovered in print over the next year — including re-releases of old 78 rpms from the 1920s; regional and European outfits; synagogue and community groups; and the handful of professionally produced, contemporary albums by the visionary groups that I would dub avatars of “the klezmer renaissance,” including the Klezmatics.

I did what I could to gather up all these resources; I interviewed all the significant players; and I wrote the first guidebook to the music, “The Essential Klezmer,” which was published by Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill in the year 2000. In addition to short reviews of all those 300 albums, the book traced the evolution of the music from the Old World shtetls, where its antecedents were born, through immigration to the U.S., where it was shaped through a give-and-take with American music in the prewar years, before being rediscovered and revived in the 1970s and 1980s by a whole new generation of players, those who approached it no differently from revivals of any other traditional or ethnic music – like Bulgarian choral singing or Balkan brass bands.

While “The Essential Klezmer” told the stories of the “essential” figures of the klezmer revival – including Hankus Netsky and the Klezmer Conservatory Band, Andy Statman, and the members of Brave Old World, among others — in some basic way, the book really set out to answer the question posed by the Klezmatics that night at the Knitting Factory — what the hell is going on here? Since when was Jewish hip?

For me, it all goes back to that night with the Klezmatics at the Knitting Factory, when I discovered there was actually such a thing as my music, music that on the one hand rocked with the power of my favorites like Bob Dylan, the Band, Bruce Springsteen, Patti Smith, Bob Marley, and the Clash, while on the other hand music that spoke to me on the deepest ethnic and spiritual level, music that rekindled a long dormant attachment I had to the sounds of my people – indeed, music that defined the very concept of “my people” for me in a way that nothing else – not youth group, not Hebrew, not Israel, not synagogue … not even Woody Allen – ever quite captured.

The Klezmatics’ music would become the soundtrack to a personal religious journey and reawakening; the basis for my young children’s understanding and enjoyment of the rhythms of Jewish life during their early years; the music we would enjoy as a family in which not all of us were Jewish but in which all of us could dance and sway and sing to the same sounds; and music that would open an entire world of new Yiddish culture and creativity for me – bringing me back full circle to the destiny I first felt as a child when I learned that we were from the same family as the author of those books on my grandparents’ shelves that bore the name “Peretz” (my mother’s maiden name), and that someday I might do something that would live up to the weighty legacy of my ancestor, Y.L. Peretz.

The Klezmatics were the embodiment of this dynamic, and as it turned out, I was about a decade late to the party. The group was formed in the fertile downtown music scene on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1986; the Klezmatics are now celebrating their 30th anniversary with a terrific new album, the perfectly titled “Apikorsim/Heretics” (World Village) and a marquee performance at Town Hall in Manhattan on Thursday, December 1. Over the years, the Klezmatics have expanded their breadth and depth to include contemporary folk, with their cover of Holly Near’s “I Ain’t Afraid,” on their 2002 album, “Rise Up! Shteyt Oyf!,” and in a couple of albums of songs based on unrecorded Woody Guthrie lyrics. (The Klezmatics are the only Jewish music band to have won a Grammy Award; ironically, it wasn’t for one of their Yiddish albums but for their Guthrie-based album, “Wonder Wheel.”)

“Apikorsim” finds the group returning to their Yiddish-song based roots, powered by cofounder Lorin Sklamberg’s inspirational vocals; rewriting new versions of semi-obscure Yiddish melodies; and unleashing the collective’s exotic compositional tendencies, with various members contributing new tunes based on old modes and sonorities juiced by the instrumentalists’ jazz and world music chops and their deft sense of improvisation, much of it orchestrated and arranged by cofounder and trumpeter Frank London. The album takes me back to the aptly titled “Possessed,” the recording that first grabbed me and never let me go. Twenty years after that one, and 30 years since the group’s first release, “Apikorsim” likewise boasts the power to possess a listener like a dybbuk.

Seth Rogovoy is a contributing editor at the Forward and the author of “The Essential Klezmer: A Music Lover’s Guide to Jewish Roots and Soul Music” (Algonquin Books, 2000). He is the artistic director of the annual Yidstock: Festival of New Yiddish Music, at the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Mass.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO