Remembering Zelda Fichandler, ‘Great Founding Rabbi’ of Regional Theater

Image by Arena Stage

The American Jewish stage producer, director and educator Zelda Fichandler, who died on July 29 at age 91, was more than just the cofounder of Washington D. C.’s much-lauded Arena Stage and longtime inspiring mainstay at the graduate school of acting at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. She was, as Todd London’s “An Ideal Theater” asserts, the “great founding rabbi of the regional theater” in the USA. How did she manage to achieve so much? By unsurpassed skills of persuasion, using what London calls her “dazzling, Talmudic mind.”

Part of the dazzle was a firm instinct for what plays to present, keeping in mind that the goal was to create theatrical life far from Broadway. One landmark success was the American Jewish playwright Howard Sackler’s “The Great White Hope” (1967) starring James Earl Jones as an African-American boxer interacting with his Jewish manager Goldie. “The Great White Hope” won a Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1969 and transferred to Broadway, a first for regional theater. In 1973, Arena Stage was the first regional theater to tour Soviet Russia. Fichandel cannily chose the quintessentially American plays “Our Town” by Thornton Wilder and “Inherit the Wind” by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee. Although not revolutionary repertoire, “Inherit the Wind” especially, with its show trial atmosphere and debates about evolution must have resonated with audiences in the USSR, where not long before, Stalinist show trials resulted in judicial murder of thousands.

Back in D.C. in the 70s, there was Elie Wiesel’s “Zalmen or The Madness of God” about anti-Semitic oppression in Stalinist Russia. First published in France in 1968, it was not seen in English translation until, as Wiesel explained in his memoir “All Rivers Run to the Sea,” the director Alan Schneider, born Abram Leopoldovich Schneider in Kharkov, took an interest in the play. As a longtime collaborator with Arena Stage, including as artistic director, Schneider recommended it to Fichandler.

The mighty labors involved in fundraising, budgeting, producing, and often rescuing a small independent theater from near-disaster required great self-abnegation, as Fichandler explained in 1979 to an interviewer from “Group,” a publication of the Eastern Group Psychotherapy Society. Family matters had to take second place, she recalled.

“I had to give a dedication speech for a new building the day after my mother died. And there were 500 people coming. And my mother was not going to be buried because of Jewish tradition of Shivah. She was in the morgue at that time. And I had to not let that interfere. I had to transcend that… and let as few people know as possible. I told a few people,” she said. “I told a few people in case I couldn’t deliver, I told them what the problem was. But for the greater number of people, I never told them. Because there isn’t room in the theater. If everybody brought in what happened to them… it’s just the opposite of the therapy group I should assume… You’re not supposed to bring your private life in if you can can help it.”

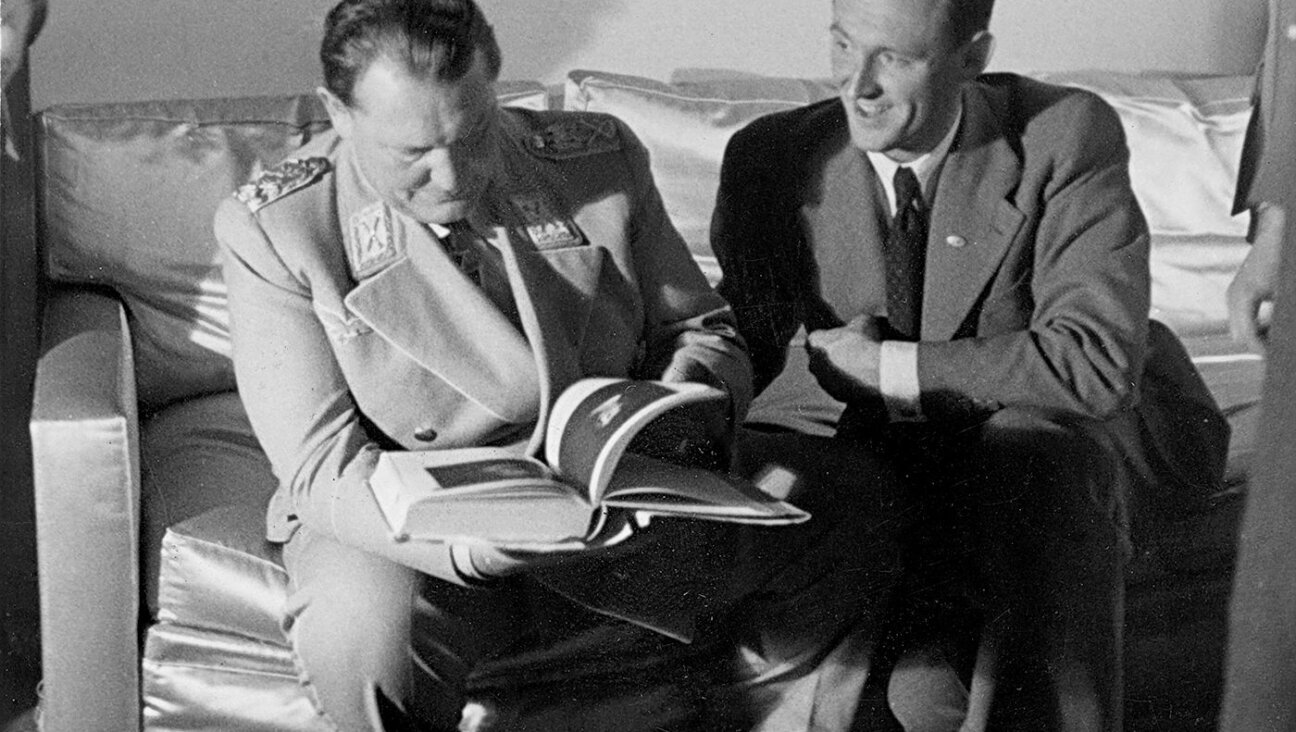

Arena Stage co-founders Zelda and Tom Fichandler during the construction of the Kreeger Theater in 1971.

Fichandler’s pensively planned productions may have been inspired in part by the intellectual strength of her forebears. Born Zelda Diamond, she was one of the two daughters of the Russian Jewish émigré Harry Diamond (1900 – 1948) a radio pioneer and inventor who developed essential designs for automatic explosive devices that were set off when they approached a target. Later, these so-called proximity fuzes would be described by the United States War Department as “one of the outstanding scientific developments of World War II … second only to the atomic bomb” in military importance.

His daughter had her own explosive intensity, in reimagining works thought to be familiar, such as a 2006 Arena Stage production of “Awake and Sing” a play from 1935 by Clifford Odets, about Bessie Berger and her impoverished family in the Bronx. Originally performed by such American Jewish stage luminaries as Morris Carnovsky, Sanford Meisner, Luther Adler, and John Garfield (born Jacob Julius Garfinkle), the play was dated a few decades after its first performance. To freshen up the text by adding authenticity, Fichandler consulted an early version of the play, originally entitled “I Got the Blues,” surviving in manuscript form at the Library of Congress. It contained far more Hebrew, Yiddish, and all-round Yiddishkeit than the later published version of the play.

“We’ve made the choice in this production to restore the Yiddishness of the original version, imagining that if Odets were alive today, with Yiddish having entered and affected the English language as it has, he would agree with that choice and find it in tone with the lyric uplifting of blunt Jewish speech, boiling over and explosive, that characterizes his writing,” Fichandler stated in a program note.

And as the daughter of Harry Diamond, Fichandel knew her munitions. As she told the theater director Anne Bogart in 2004 her early choice of theater as a life work, after majoring in Russian language, was empowered by her “ability to use logic to get from this point to that, something I think I learned from my scientist father. To get what I want by charting a path from A to B. It was a kind of ‘wiliness,’ what in Yiddish is called ‘saykhel,’ which means, I guess, good, common horse sense.”

One year later she wrote an essay about acting, “The Lying Game,” for “American Theatre” in 2005 as ever inspired by Yiddish: “Stella Adler once quoted her father Jacob, patriarch of the Yiddish theatre, on the reasons why someone wants to become an actor: ‘You don’t want to get up early, you don’t want to work and you’re afraid to steal.’” After this humorous start, she concluded with a quote from Arthur Miller’s essay “On Politics and the Art of Acting.”

“However dull or morally delinquent an artist may be, in his moment of creation, when his work pierces to the truth, he cannot dissimulate, he cannot fake it. Tolstoy once remarked that what we work for in a work of art is the revelation of the artist’s soul, a glimpse of God. You can’t fake that,” she wrote.

Benjamin Ivry is a regular contributor to the Forward.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO