The Forgotten Gizmo That Brought Us Closer to the Holy Land

Image by Wikimedia Commons

Some academics I know have been quick to avail themselves of the latest digital tools so that they might communicate more effectively with their tech-savvy students. Others are more apt to roll their eyes or dig in their heels at the prospect of actively integrating technology into their teaching. Hoping to convince the skeptics among us of the folly of their ways, my department recently invited several skilled practitioners of the digital humanities, as they’re called, to strut their stuff. In short order, references to “visualization” and “computational strategies” filled the air. These techniques, we were told, constituted the “last word” in the production and dissemination of knowledge.

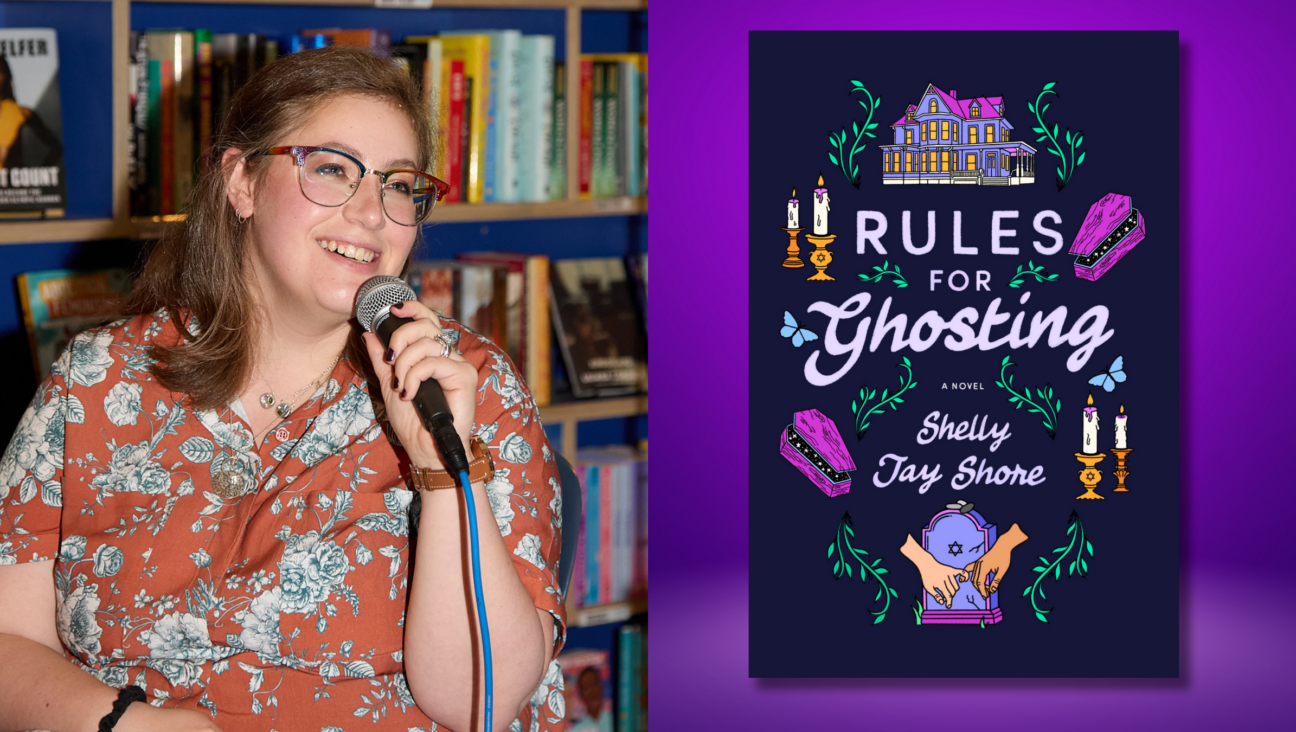

You’ll get no argument from me. All the same, I was struck by the fact that 80 years earlier, the very same expression was linked to the use of another technological marvel: the stereopticon. Writing in The Elementary School Journal of June 1925, Bertha Shannon Moore of Washington, D.C., reported that the installation of electric lights at her institution, the Carberry School, “was an achievement, but a stereopticon was the last word.” She went on to point out that “in awakening interest, in imparting instruction and in giving pleasure, as well as in developing initiative, it has gone far beyond expectations… its possibilities are unlimited.” (Sound familiar?)

Moore’s enthusiasm for the stereopticon, a device said to do for the eyes what the phonograph had done for the ears, was widely shared. An adumbration, on a rather small and modest scale, of the motion picture, it projected three-dimensional images onto a blank wall or screen, transforming them into what one devotee called a “life-size space, a life-size representation.”

Owing to its bulkiness, the cumbersome stereopticon was limited at first to institutional use, but over time it slimmed down, becoming increasingly portable. Underwood & Underwood, for example, boasted of its “famous academic dissolving stereopticon.” Just as “powerful and efficient” as its predecessor, this “simple, light, compact” model and those that followed in its wake were intended for use at home as well as in the lecture hall.

Americans put their stereopticons to good and varied use. Some drew on the device to teach geography, look at birds and insects, lampoon political opponents, sell a product or familiarize audiences with the latest archaeological discovery. Others used it to make a point. With barely concealed amusement, The New York Times told of an Omaha, Nebraska, reverend who, with the aid of stereopticon slides, hoped to demonstrate “conclusively” that Jonah lived within the belly of a whale for three days and nights. “I have slides to prove that Jonah was able to stand up and walk around inside the whale,” the Rev. O.G. Bellah insisted in 1927.

Enlarging America’s capacity for wonder, stereopticon slides also brought the nation closer and closer to the Holy Land. No longer did Americans have to rely on their imaginations, or on those of their pastors, to summon up an image of the biblical landscape. Instead, they could choose from among hundreds of sets of slides of sacred sites — of Jerusalem and Shiloh, Tiberias and Cana. Screening these images within the comfort of their parlors, they could indulge in a spot or two of armchair travel with Jesse Lyman Hurlbut’s “Traveling in the Holy Land Through the Stereoscope” as their reliable guide.

At once a revelation and an inspiration, the stereopticon found its most resolute champions among Sunday school teachers who deployed the up-to-date technology to familiarize their young charges with biblical wisdom. By visualizing the flora and fauna of the ancient Near East, the stereopticon brought the Scriptures to life, setting its lessons within a recognizable context. It also made their jobs a lot easier. As one Sunday school instructor enthusiastically observed, with a stereopticon at the ready, “I could in a trice throw a few scenes of the lesson before the student’s eyes. They could see at least the geography of the assignment. The Bible is connected solidly with this planet and this life!”

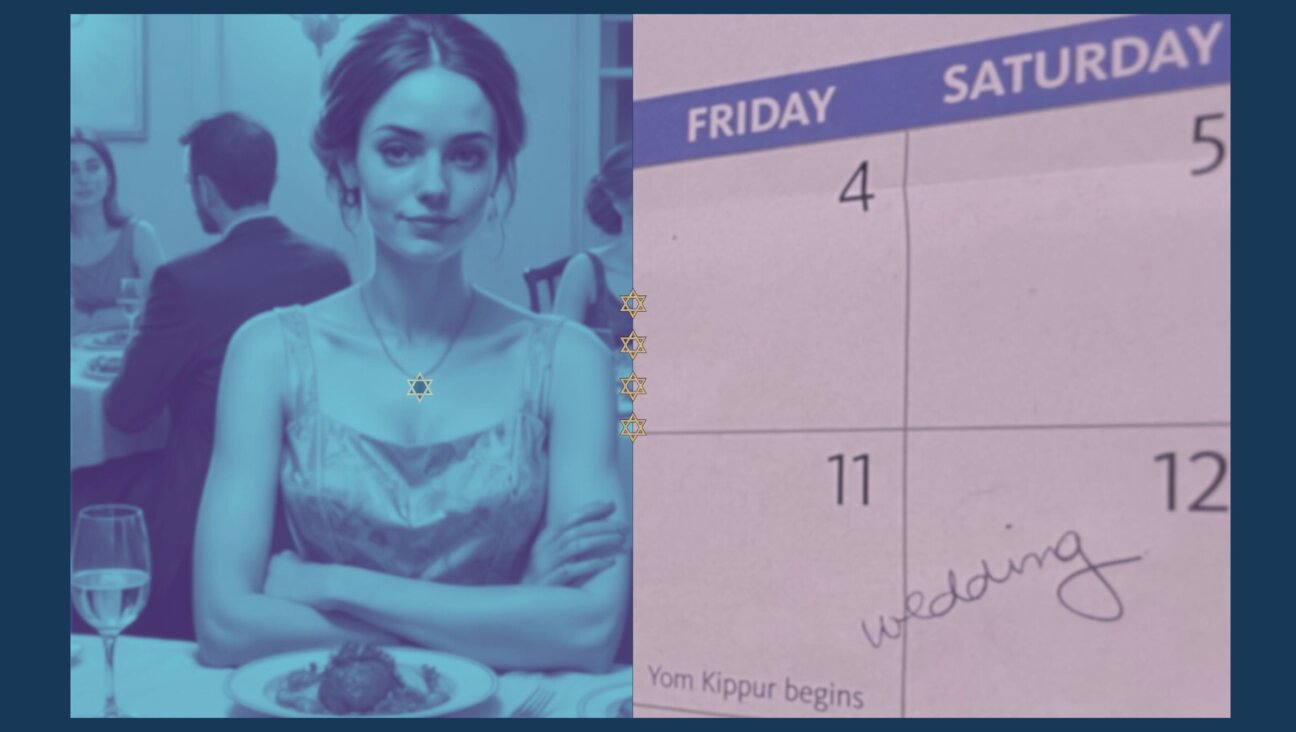

Some Americans were so taken with the opportunity to connect to the Bible that they went further still: by “reproducing” the Holy Land in their own backyard. I kid you not. In June 1931, Mrs. Martin W. Littleton of Manhasset, New York, imported a young artist named Frida Abraham from Jerusalem to paint a panorama of Palestine on the wall surrounding her garden. Rendered in the “vivid colors peculiar to that cloudless atmosphere,” it depicted Jerusalem and Jaffa, the Sea of Galilee, the Dead Sea and the River Jordan as if lifted straight from the pages of the Bible.

Mrs. Littleton, who greeted visitors to her home clad in the “robes of ancient Palestine,” was pleased as punch with her commission, whose timelessness accorded perfectly with her views on the Holy Land. “Nothing has changed in that country in 2,000 years,” she related.

In our own day, as in Littleton’s, some things, be they topography or technology, stubbornly remain a matter of faith.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO