Say Hello to ‘Mr. Yiddish’

King of Yiddish

By Curt Leviant

Livingston Press, 305 pages, $30

When Shmulik Weingarten arrived in Israel in 1950, authorities in higher education discreetly advised him to change his name. As the narrator of Curt Leviant’s novel “King of Yiddish” tells us, “Even though all the founding fathers of Israel were born into that supple, juicy, evocative, folk-saturated, wise, witty and image-laden Yiddish tongue,” Israeli bureaucrats looked down their noses at Yiddish in favor of the nation’s chosen language, Hebrew.

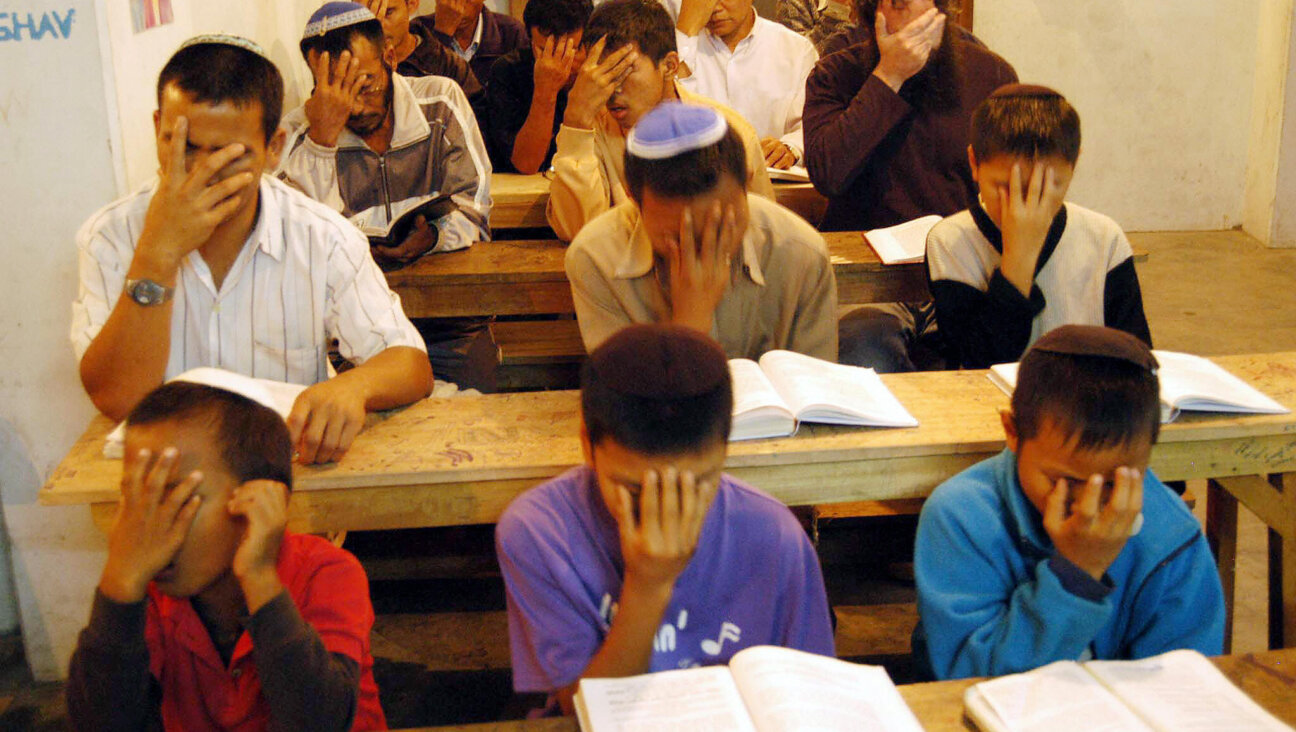

So Weingarten (literally, “wine garden”) changed his name to Gafni (“my vine”), a kind of “nose job” on the family name. Yet Gafni’s interest — no, love — for Yiddish cannot be deterred, and in short order he establishes a Yiddish Studies Department at the University of Israel in Jerusalem, where he quickly advances to “Professor, Chairman and Distinguished University Researcher of Yiddish Language, Literature, Culture, and Folklore.” Soon Gafni is a world-renowned guardian of Yiddish: a faithful recorder of “Yiddish folklore, editor of Yiddish drama, anthologist and preserver of Yiddish poetry and prose, harvester of Yiddish humor and expert on earthy Yiddish expletives.” Or, in the words of an esteemed colleague, “Mister Yiddish.”

When we first meet Professor Shmulik Gafni, aged 70, he is fit and healthy, although a minor heart attack has prompted him to wear a chaver (friend), the Israeli version of a Life Alert button. He is a loving and devoted husband, who has been married to the same woman for 40 years. He has a son living in Seattle and twin daughters living in Jerusalem. The twins have daughters, too, and there is even a great-granddaughter, making Gafni an elter-zeyde (great-grandfather). The only cloud over this idyllic family scene is that his beloved wife, Batsheva, is suffering from advanced diabetes.

Thus, we meet the hero of Leviant’s seriocomic novel — a book Leviant is aptly qualified to write. Leviant is a native Yiddish speaker born in Vienna, a retired professor of Jewish Studies at Rutgers University, and an internationally recognized English translator of such Yiddish luminaries as Sholem Aleichem, Chaim Grade, and Isaac Bashevis Singer — not to mention a successful and prolific author of novels and short stories in his own right.

Leviant is also a master of loshn which, in Yiddish, means both language and tongue. His language is vivid, visceral, and packed full of puns, imaginative word play, and an occasional bad joke: “Macademia: where nutty professors go when they retire.” When it comes to tongue, Leviant often has it planted firmly in his cheek.

On the other hand, Leviant’s love for Yiddish is expressed in a serious and powerful way: “The Holocaust was more than the death of a people, Gafni felt. It was the murder in four, five, even six dimensions: it was also songs and jokes, word plays, folk expressions, foods, recipes, games and ditties, insults, proverbs, riddles, lullabies, gestures, future works of art and literature, inventions, cures.”

Shmulik Gafni’s life mission is to preserve this lost Yiddish world — to hold onto Yiddish in all its iterations, especially those of his childhood home in Warsaw, where, in the words of his uncle, “Life was so Jewish that even the walls spoke Yiddish.”

But Gafni’s work is disrupted by forces that speed along like two trains on a collision course. The first is his obsession with finding the murderer of his father in a Polish pogrom, an attack that occurred 14 months after the war’s end. And the second is his strange infatuation with a Polish graduate student, Malina Przeskovska, a fascination that seems to fly in the face of everything he holds dear.

The death of Gafni’s father is tragic. Most of his family members perished in the death camps, but Gafni’s father and uncle miraculously survived. Gafni, too, miraculously escaped death by fleeing to the Soviet Union, where he fought as a partisan in Polish and Russian units. Fourteen months after the war, as he headed back to Warsaw, Gafni asked his father to meet him in the Polish town of Kielce, where his uncle now resided. But when Gafni arrived, he found a terrible commotion in progress. Running to the edge of the forest, he is staggered to see Poles killing Jews. Standing there in horror, he watched as a man murdered his father and uncle. This man’s face will be forever etched in his memory, and Gafni will seek vengeance for the rest of his life.

The alternating plot line, Gafni’s fascination with his Polish student Malina, is much more complicated and confusing. When Gafni’s beloved wife Batsheva dies from diabetes — and after the religiously prescribed period of mourning — Gafni sets forth to woo and marry Malina. Of course, he knows their relationship will be perceived as scandalous; his family, friends and colleagues will portray him as an apostate and betrayer of history. “How could a man who was universally regarded as the world’s greatest expert not only of the Yiddish language, folklore and literature, but Yiddish everything, marry a Polishe, a Polish gentile Christian Catholic goyishe shikse from a land where the ashes of three million Jews still hovered in the air?”

Yet something uncanny and provocative draws Gafni to Malina, like the proverbial moth to a flame. Gafni knows the risks, but is unable to stop. He hopes that one day he will be able to say loud and clear to his children and everyone else, “See, that was why I married her. There was a reason after all.” But until he can discover the reason, he must simply chalk it up to fate: “What is destined to happen will happen and nothing will change it, not time, not place of residence, not disguise, not error, not bewilderment. What is destined is written as if on a film, and whether or not the film is seen, whether or not people shout or protest in the theater, the end will still be the same.”

Curt Leviant’s “King of Yiddish” deftly propels us through reality and fantasy, mysticism and superstition, truth, lies, and innuendo, and the unending tension between Jewish and Polish relations. As the forces of destiny converge, questions abound: Is a collision inevitable? If so, who will survive? And in the end, will we be left with laughter or tears — or perhaps a little of both?

Scott Hilton Davis is the author of “Souls Are Flying! A Celebration of Jewish Stories” and is the founder of Jewish Storyteller Press.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO