A New Arab Museum on the Periphery

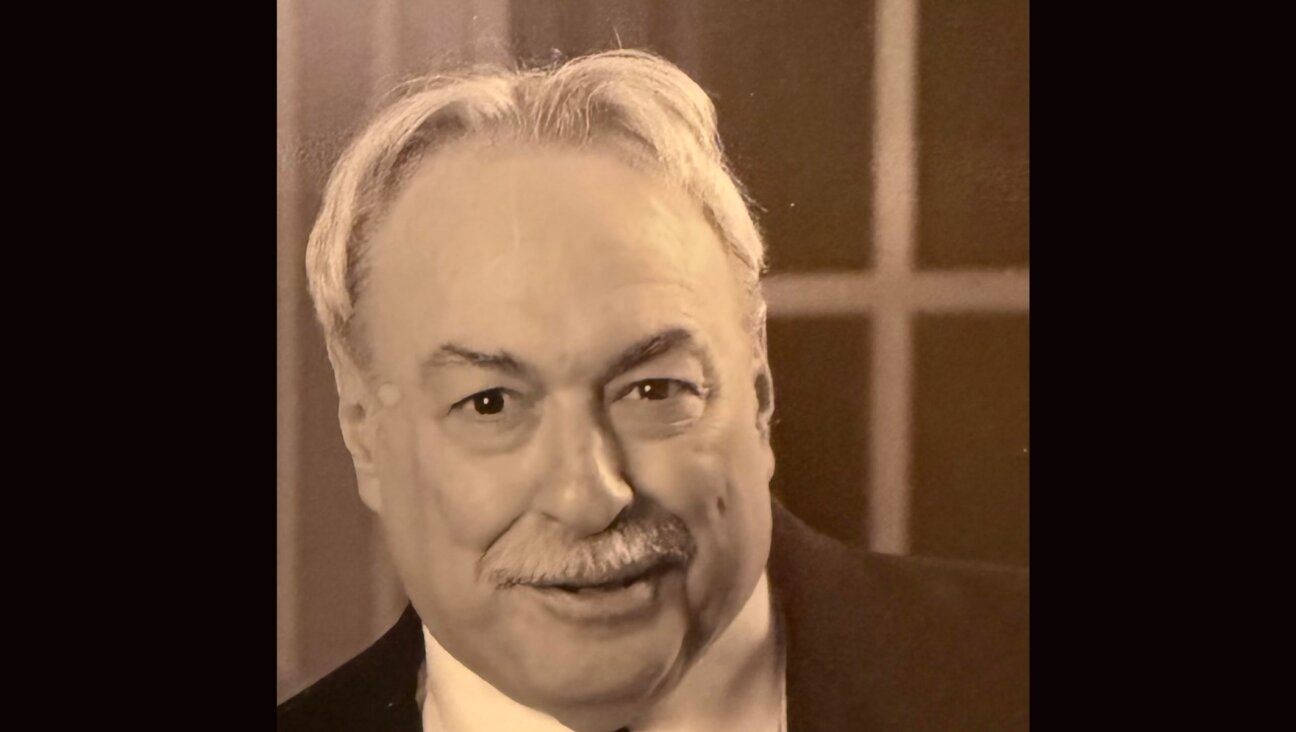

Self Portrait? Photographs by French-Moroccan artist Mehdi-Georges Lahlou are among the museum’s most provocative. Image by Mehdi-Georges Lahlou

“Our trip is canceled. The atmosphere in Sakhnin is very tense.”

It was December 10, 2014, the night before I was due to visit the newly established Arab Museum of Contemporary Art, in Sakhnin, an Arab-Israeli city in the north of the country. I had received the phone call from the Haifa-based, Romanian-Israeli artist Belu-Simion Fainaru. As one of the museum’s directors and its co-founder, he had been advised not to go, following the death of a Palestinian minister, Ziad Abu Ein, during a West Bank protest earlier that day. The cause of death was disputed: Some Palestinian witnesses and officials said he had died following a confrontation with a member of the Israeli border police; the Israel Defense Forces said it was a heart attack.

In the past, Sakhnin — a city with a majority Muslim population and a sizable Christian Arab minority — has been perceived as a barometer of Arab-Israeli opinion. Certainly, the reaction to this particular incident demonstrated how the Arab population in Israel is affected by such flare-ups and disputes.

•

Four months later I was on a car-choked highway, heading out of cosmopolitan, commercial Tel Aviv bound for Sakhnin. It was Passover, and it seemed that all of Israel was on the move. Cars full of vacationers making the most of the holiday period passed by, stuffed with camping equipment and luggage.

Sakhnin is located in the Lower Galilee, in a valley surrounded by mountains, about 25 kilometres from Akko. Clusters of houses, some only half-constructed, are built into the hills in the outlying area. Gold and green minarets dot the rugged, agricultural landscape, which is covered by olive and fig groves and by bursts of emerging spring flowers.

The main road through the valley runs through the city. Lined with cafes, clothes shops and cheap-looking furniture outlets, it has a dilapidated air. There are no street names; the odd sign is written in Hebrew and Arabic. Primarily known for its soccer team rather than for its art, Sakhnin is home to Bnei Sakhnin, one of the first Arab teams to play in the Israeli Premier League. Last November, a game against the nationalist team, Beitar Jerusalem, made headlines as it ended in a confrontation between players. Relations are known to be tense between the two teams, according to Gershon, my taxi driver. In order to keep the fans apart during home games, special parking is provided for Beitar supporters some 5 kilometers out of the city. Police-escorted buses drive them to and from the game.

Finding the museum proved to be difficult. Finally, after turning off the main thoroughfare, down a narrow, dusty side road, past a football stadium, I arrived at the Center for Environmental Research and Education. The museum is within this building. Its official address is 100 Doha Street, but no one knows it as that, Fainaru said, greeting me. As if to prove his point, he asked the caretaker the address of the center. The caretaker shrugged his shoulders in response, shook his head and offered, “Rehov Stadium?”

“This museum is in the periphery of the periphery,” said the Israeli artist Avital Bar-Shay, the other founder and director of AMOCA. “We wanted to make art accessible for everyone, not just people in Tel Aviv.” Bar-Shay and Fainaru came up with the idea of AMOCA after the success of the Mediterranean Biennale in 2013, which they had set up and curated, also in Sakhnin. Works of art were exhibited all over the city, including at the center. “The whole city was full of art,” Fainaru said. “In restaurants, in City Hall, in offices. It brought the Israeli public to the area.” Their hope is that AMOCA will do the same.

AMOCA is the first museum of its kind to open in an Arab-Israeli city that had, until the biennale, little contact with contemporary artworks. The museum now holds a collection of more than 200 contemporary works of local and international art, with an emphasis on artists from Arab and Mediterranean countries. Funding has come from the Ministry of Culture, as well as from institutions abroad. The project has the support and cooperation of the municipality, including the mayor of Sakhnin, Mazen Ghanayem, but finances — and practicality — meant that an existing building was needed to house the project.

The center is, however, a magnificent showcase. It contains traditional Arab architectural techniques, that ensure cool air and natural daylight, merged with modern ecological building benefits such as wind and solar generators. Constructed from adobe or mud bricks — an ancient building method that provides effective thermal conditions in both summer and winter — it was designed by Abed Elrahman Yassin, a student of the late, notable Egyptian “architect for the people,” Hassan Fathy, who re-established the use of mud bricks. High, slated windows tame the bright glare of the midday sun, and arched doorways lead out to a semi-shaded central courtyard.

Schoolchildren buzzed in and out of one of the classrooms and, despite their noise and clatter, the green building still exuded a sense of calm. Students come here to learn about the center’s eco-design and engineering. How much attention they give to the artwork that lines the walls of the ground floor is anybody’s guess.

“Museums today are not just about safeguarding art; there has to be an agenda to the museum,” Bar-Shay told the website ISRAEL21c last December. “Our vision is that the project is a dialogue between Jews and Arabs,” Fainaru said. “Art is the meeting platform.”

To further this, the museum’s first exhibition is titled “Hiwar” (Arabic for “dialogue”) and presents a diverse selection of art from its permanent collection, by Jews and Arabs. Works include paintings, photography and installation pieces by artists from Algeria, Turkey, Afghanistan, Israel (including Fainaru) and Egypt. Druze and Palestinian artists are also represented. Unknown local artists — many of whom have not been exhibited before — are displayed next to those of international caliber, such as the South African-born Israeli Larry Abramson and the Israeli sculptor Dani Karavan.

Photographs by the French-Moroccan artist Mehdi-Georges Lahlou are perhaps the most mesmerizing, playful and provocative pieces in this exhibition. Born to a Catholic mother and a Muslim father, his work addresses the cultural meeting between Islam and the West, questioning issues of identity and gender. Here, a series of photographs portrays the figure of a woman wearing a veil, taken from different perspectives. Yet the woman is actually the figure of the artist himself.

An autobiographical element is also present in photographs by the Palestinian artist Raed Bawayah. His pictures reflect distorted memories of his childhood village home near Ramallah. There is an emphasis on the human dimension of his subjects, be it the image of boys and a goat or of a woman breastfeeding, but a wider political message always exists in the background.

Tucked around a corner are two of Bohtaina Abu Milhem’s untitled dresses. Her work is passionate and unusual. Embroidery is typically a female craft within Palestinian society, and Milhem expresses herself through her use of fabrics and dresses associated with fashion and design in popular folk culture. Using a mix of needles, threads and pins, her medium combines Arabic lettering and signs and symbols with folk aphorisms connected to Arabic culture.

Despite being open to the public since December 2014, the museum’s official opening date has been postponed several times, sometimes as a result of political issues and tensions. During the Gaza war last summer, Fainaru described the atmosphere in the city as strained and says that there were demonstrations. But since then his work with Bar-Shay has accelerated. Their wish is to try and counter the conflict between Jews and Arabs with something positive. “Art can’t influence politics,” Fainaru said on a local radio station, “but it can influence the mentality of people.”

Fainaru admits to idealism. Bar-Shay does, too, but she said: “We’re idealistic but not innocent. We’re optimistic.”

Their optimism and drive are remarkable, particularly at a time when the peace process has more or less slipped off the political agenda. The lack of an Arab co-founder has meant that it has been more challenging, Fainaru admitted when we talked in December. Their interaction with the Arab population and municipality has not always been straightforward. “Putting an exhibition in an Arab town is political in itself,” Bar-Shay said. The cultural differences and different expectations between them mean that “it is not an easy dialogue,” Fainaru explained, “but what is important is to try and keep the dialogue.”

This current exhibition will run until December of this year. Fainaru and Bar-Shay are also in the process of organizing the third Mediterranean Biennale, which is due to open in 2016 and will continue until that summer. AMOCA’s official opening is set for June 17. By then, small omissions such as the lack of picture titles will be rectified, and the visionary project will be launched — hopefully with the attention and endorsements it deserves.

Anne Joseph is a London-based freelance journalist.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO