Looking for S. An-sky’s Papers, I Found Historical Gems Lost to Decay

S. An-sky himself Image by Wikimedia Commons

The Judaica department of Ukraine’s vast state library — one of the 10 largest in the world — occupies five rooms on the fourth and top floor of a Soviet-built branch of the system’s archipelago of buildings, which are spread across Ukraine’s capital. In a nod toward Ukraine’s energy crisis, the building is drafty and chilly, and the lights are turned off during the day, giving it a permanent feel of after hours. There are no elevators, and its few staff and even fewer visitors steadily scale the stone staircases, barely making a sound as they shift from one floor to another.

In the Jewish ward upstairs, potted plants line the reading room’s large windows, which look out onto some of the city’s prerevolutionary rooftops. Inside, a band of women carefully and assiduously maintains the collections.

There are priceless gems in these archives: Marc Chagall illustrations, Jewish calendars dating from the mid-19th century, and a vast compilation of Jewish children’s literature from the 1920s and ’30s. But I have come to view the collected papers of S. An-sky, the renowned Yiddish playwright, fiction writer, journalist and ethnographer from the turn of the 20th century, whose most famous drama, “The Dybbuk,” tells the tale of a young bride possessed by a demon.

“It’s getting to the point where we don’t want people to touch them,” chief librarian Anna Rivkina told me, referring to An-sky’s manuscripts, which sit amid stacks where the pages are slid, unprotected and with no temperature control, between flimsy cardboard. “Some are over 100 years old, and I pity them.”

Rivkina, who taught herself Yiddish in the 1990s after first hearing it at home 30 years previously, is a loving custodian for these papers, as is Irina Sergeyeva, the library’s head of Judaica and one of the world’s foremost An-sky experts.

Sergeyeva informed me that half of the slowly decaying collection has been digitalized. The rest should be completed by mid-2015, she said. But the funds for this are yet to be allocated to the library, which relies on donations and grants from the state. More important, there are no plans to protect and conserve the originals — a crucial step that archivists consider fundamental. Such a plan would mean instituting climate controls for the collection and giving them better protection than their current cardboard cover sheets.

How likely any of this is in light of the country’s 6-month old war with Russian-backed separatists and a debilitating debt crisis is dubious. Meanwhile, I and other visitors are allowed to handle original An-sky manuscripts and documents — many of them in poor condition—with our bare hands.

It was in the fall of 1914 when Baron Vladimir Ginzburg, a Kiev banker and Jewish philanthropist, wrote to An-sky about the writer’s expeditions through the shtetls of the Russian Empire, which Ginzburg had been sponsoring. The latest expedition had been cut short by the outbreak of World War I as Jews fled the violence engulfing them. An-sky found himself suddenly helping waves of Jewish refugees.

“The collection of things for the refugees has produced excellent results,” Ginzburg wrote in purple fountain pen on cream-colored stationery, summing up what he’d heard from An-sky. His initials, V.G., are stamped on the top left corner, underneath a four-pointed blue crown. All these details are vivid in a way they can be only when the eye beholds the original.

As for An-sky, in a lengthy manuscript titled “Certain Facts Regarding the Legal Status of Jews” he wrote, “The soldiers seem to be of some value when it comes to the right of residence,” hinting at the complex relationship between imperial Russian soldiers and Jews.

Like all of An-sky’s ethnographic missions, which took place between 1911 and 1914, Ginzburg enjoyed being informed every step of the way. These handwritten texts — dog-eared and grease stained, yet gracefully penned in Russian and Yiddish — are just two of the 1,335 An-sky-related manuscripts in the library’s collection.

Born in present-day Belarus in 1863, in near the city of Vitebsk — the same region where Chagall would be born 24 years later — An-sky was an extraordinary figure. His contributions to the understanding of Jewish life in the Pale of Settlement, as this heavily Jewish populated area was known, put him on a par with figures such as Sholem Aleichem.

Born Shlyome-Zanvl Rapaport, (S. An-sky was his nom de plume) there were few avenues of written creativity he didn’t prolifically venture into: He composed short stories, poetry, journalistic articles, translations of French literature, ethnographic work and, of course, plays. “The Dybbuk” has been adapted to a dizzying array of different media in varied languages since An-sky wrote it in 1914, from film to opera to radio, and even a ballet in 1974, composed by Leonard Bernstein and choreographed by Jerome Robbins. The original Yiddish manuscript of the play is lost.

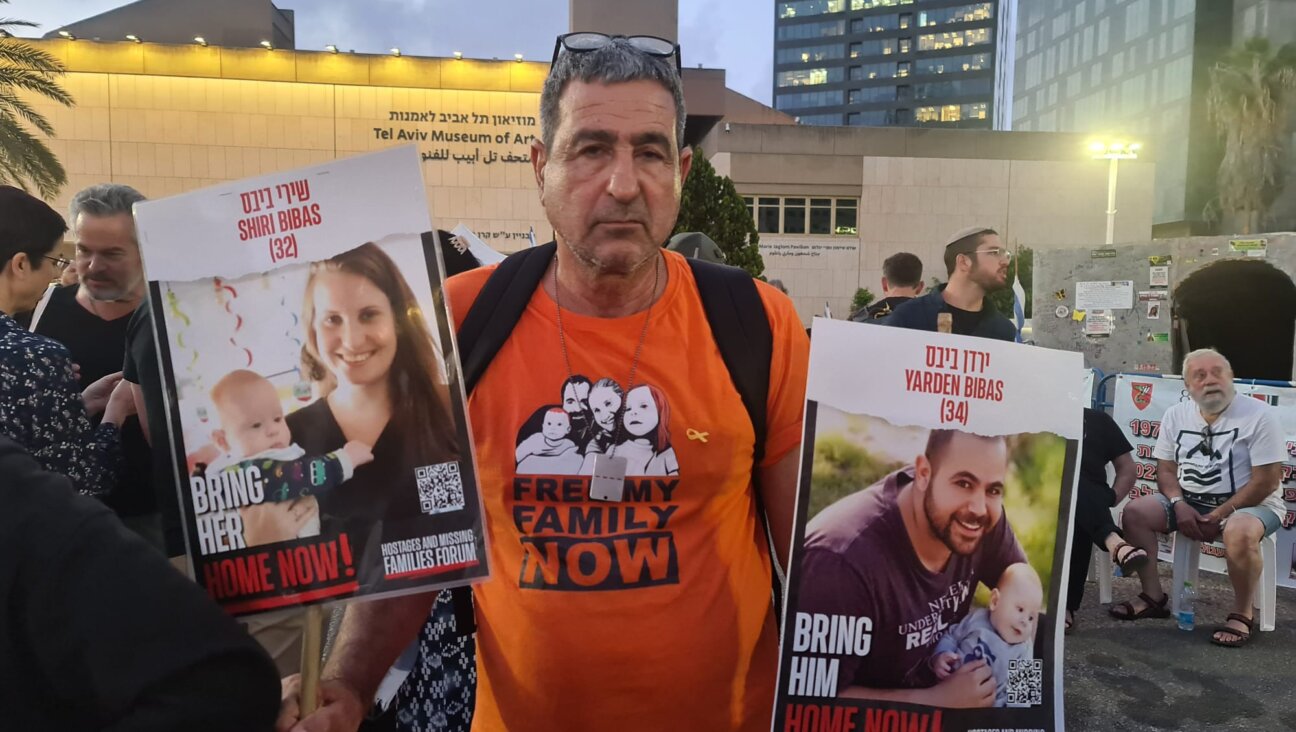

Testimony: The archives hold An-sky’s handwritten notes from a blood libel trial. Image by Amie Ferris-Rotman

An-sky, who died in 1920 in Warsaw, Poland, from pneumonia on his 56th birthday, would likely have been thrilled with these translations of his vision. In his cultural outlook he was a revolutionary: He sought to promote appreciation of the folkloric ways of Jewish peasantry. His expeditions took him to hundreds of Jewish villages in the regions of Podolia and Volhynia, areas stretching across Western Ukraine and parts of Moldova, Poland and Belarus. He recorded Jewish sayings, myths and tales involving angels and spirits, along with more practical advice, such as how to correctly circumcise or give birth.

As an educated intellectual, he was fascinated by how the other Jews lived; he wrote short stories based on what they told him (including a tale about British Jewish liberator Moses Montefiore living “far beyond the seas on English land”). An-sky also recorded Jewish music and voices on hundreds of Edison wax cylinders, which are digitalized and kept elsewhere in the library.

Ginzburg wanted An-sky to explore the rest of the Pale of Settlement farther north, around Vilnius. But the war, and then the Bolshevik Revolution, got in the way. When the region of Galicia, now split between Ukraine and Poland, turned into a bloody battlefield in 1914, An-sky reported on the looting and destruction of Jewish villages and worked to get Jews out.

As I carefully removed and unfolded the manuscripts, like Rivkina I began to feel sorry for what are clearly treasures of a Jewish past that no longer exists, a world almost entirely wiped out by immigration and genocide. Sergeyeva and Rivkina have become the caretakers of ghosts.

One such phantom is the bundle of notes, written in An-sky’s own hand, on the notorious 1913 Kiev trial of repairman Menachem Mendel Beilis. Accused of blood libel — the idea that Jews kill Christians to use their blood for baking Passover matzo — after a non-Jewish boy was found stabbed to death, Beilis went on trial in the last such court proceeding of its kind in Western history. His ordeal inspired Bernard Malamud’s 1934 novel “The Fixer,” which ultimately won the Pulitzer Prize.

An-sky’s “Nightmarish Riddle,” written in black fountain pen on 24 narrow pages several inches wide, were his notes one month after the trial, which acquitted Beilis after he had spent two years in a roach-infested cell. “From the Courtroom,” typewritten in Russian and crossed out in parts by pencil, is An-sky’s blow-by-blow account of the trial for a newspaper.

In a country with a rich but tragic Jewish past — 900,000 Ukrainian Jews were killed in the Holocaust — the Judaica section is an arresting testament to lives once lived and a time when Ukrainian Jews occupied a prime spot in the culture and politics of the Russian Empire. It is a far cry from today, where the traditional Jewish strongholds of Western Ukraine are dotted with memories — commemorative plaques and rebuilt, largely decorative synagogues — but are devoid of life. Other parts of the country have pockets of Jews, some 70,000, and while there has been a cultural and religious resurgence since the fall of communism, this has taken place alongside a mass exodus to Israel and the United States.

An-sky’s deep knowledge of shtetl life piqued the curiosity of Jews across the Russian Empire. Sitting at one of the library’s wooden reading tables, surrounded by Yiddish books and manuscripts, I came upon a small postcard that arrived at An-sky’s Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) apartment on the eve of the 1917 October Revolution. The sender, someone named E. Berenshtein, asked him to come to Elisavetgrad (now Kirovograd) in Central Ukraine to give a lecture on Jewish folklore. It was clearly handwritten in Yiddish with a blue pencil, and its front bears the double-headed eagle of imperial stamps.

We don’t know whether An-sky gave this lesson or not. What we do know is that as the Bolsheviks swept to power in the coming years, dissolving the Pale and crushing the pogroms with the same ferocity with which they killed the czar and his family, the shtetl culture An-sky so diligently recorded vanished forever.

Contact Amie Ferris-Rotman at [email protected]

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO