Getting Back to the Garden (of Eden)

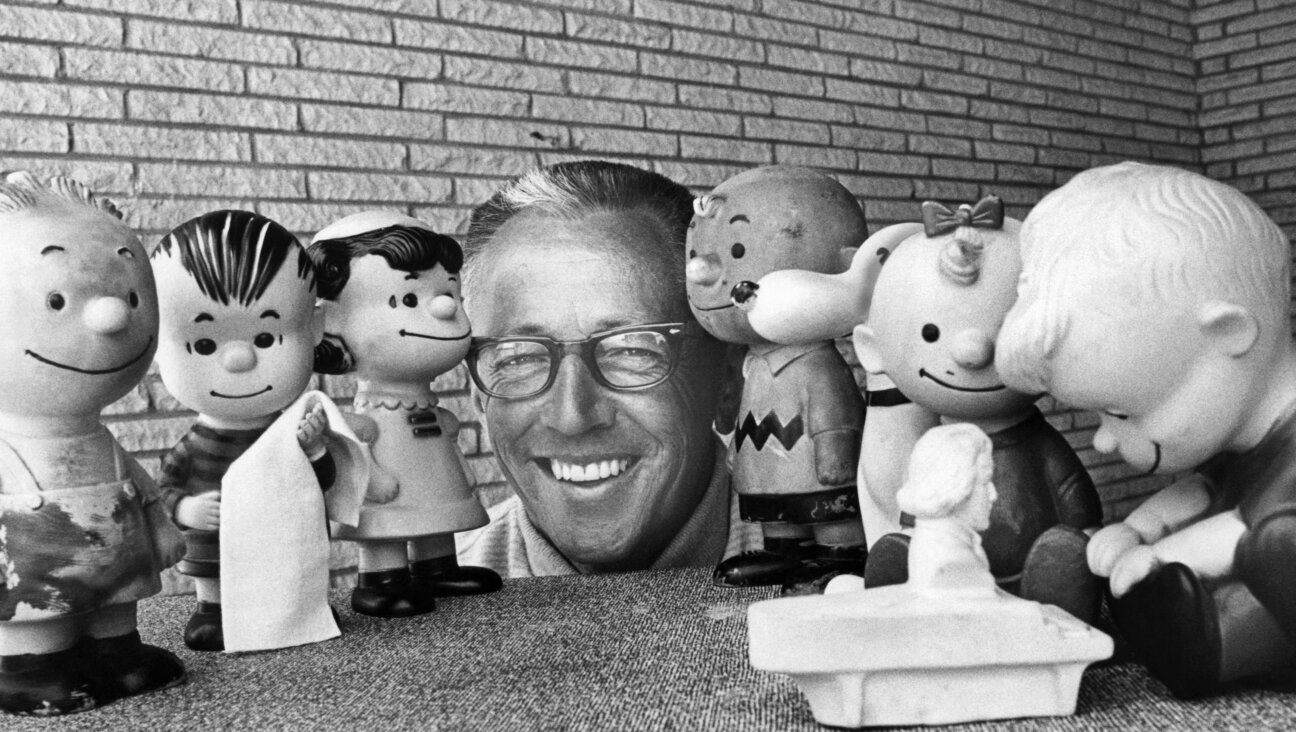

Dino-Mite: Mark Dion’s ‘The Serpent Before the Fall’ is on display at MOBIA’s ‘Back to Eden’ exhibit on the Upper West Side of New York. Image by Menachem Wecker

Looking at an image of a serpent encircling an apple branch, most of us will think of the snake from the Garden of Eden. In popular lore, Adam and Eve’s consumption of the taboo meal from the illicit Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, as it is called in the Bible, resulted in their expulsion from Eden. But actually, in Genesis, the original couple’s departure from Paradise had a lot more to do with God’s anxiety that Adam and Eve would eat from the Tree of Life.

Those who don’t study medieval theology or history or Judeo-Christian mysticism extensively likely haven’t heard nearly as often of the Tree of Life as of the Tree of Knowledge. It comes as no shock, then, that artists have continued to probe the tale of the couple who had it all, lost everything, and had to rebuild and endure despite having never forgotten the taste of the perfect life they’d once enjoyed.

According to Jennifer Scanlan, the story “takes up only a few verses in the Bible, Genesis 2:8-3:24, with just four main characters and a simple narrative that continues to resonate.” Scanlan is guest curator of the Museum of Biblical Art’s exhibit “Back to Eden: Contemporary Artists Wander the Garden.” The exhibit traces some of the ways that contemporary artists have addressed Eden in their works, whether intentionally or unintentionally; their treatments often probe the relationship between people and nature. In recent centuries, that power structure has changed, Scanlan notes. Where man was once dwarfed by and subject to threats from nature, the roles have reversed. “Most people only encounter truly dangerous snakes in zoos,” she writes. “Yet these symbols persist as remnants of a time when people had a different relationship with nature.”

Alexis Rockman’s 2013 painting “Gowanus” underscores that reversal. The artist, whose work often addresses the parasitic relationship between man and nature, takes his title from the canal, which a 2013 Popular Science article called “an absurdly, laughably polluted waterway right smack in the middle of gentrified Brooklyn.” Rockman, according to a MOBIA wall text, was inspired to create the work after hearing of a dolphin that died soon after swimming through the Gowanus Canal.

The dolphin, and other ghostly forms of sea life past, lurk beneath the surface of the water, as skyscrapers bathed in pastel tones loom above. In between, pink, blue and yellow chemicals pour into the canal in a scene of degradation and decay. All of the 38 animals that appear in the work — among them the Norway rat, the diamondback terrapin, the brown pelican — are documented in a diagram alongside the painting with their scientific names. Although aspects of the work are very beautiful, the content points to an experiment gone horribly wrong.

For a small show, the exhibit has many standouts, from two stunning medieval Bibles (one from 1483 depicts the snake with a woman’s head) to Mat Collishaw’s 2013 “East of Eden,” a mirror that doubles as an LCD screen embedded in a gorgeous and elaborate frame, where the viewer can barely make out a slithering snake and misty clouds from beyond her or his reflection. The viewer is the snake it seems, and the reverse as well. Some works reference medieval precedents — such as Fred Tomaselli’s 2000 “Study for Expulsion,” which quotes Masaccio — while others, such as Pipilotti Rist’s 2010 “Sparking of the Domesticated Synapses” and Dana Sherwood’s 2014 “Banquets in the Dark Wildness,” rely on video components.

And then there’s the snake. Lynn Aldrich’s 2002 “Serpentarium” represents the snake with garden hoses, brass connectors and nozzles, and cable ties all configured to suggest a pot. Scanlan writes in the catalog that she views the work by the Los Angeles artist as referencing the “seduction of commercialism.” “[T]his snake,” she writes, “was asking her to consume not an apple, but the ever-changing array of beautiful consumer goods in the appearance-conscious city.” Not only do the iconic green hoses twisted into the shape of a pot suggest a snake’s movement, but peering over the top of the “flower pot,” one also gets a glimpse that isn’t unlike looking down the throat of a snake.

If Aldrich’s snake is abstract, though, Mark Dion’s 2014 “The Serpent Before the Fall” is quite literal. Responding to commentators (e.g. Rashi) who noted that the biblical snake’s punishment in Genesis 3:14 of being made to crawl on its belly suggests that the snake originally had legs, Dion depicts the pre-sin serpent standing on all fours. The work, as the exhibit texts note, imagines the snake as a display at a natural history museum. The animal doesn’t convey pure evil, but it certainly has a smugness and slyness about it.

There isn’t much that is subtle about “Back to Eden,” but it’s still multi-layered and very thoughtful. Eden can often feel very far away in both time and space, like a Never Never Land that nevertheless serves as the measure for paradises of every sort. But the MOBIA show cuts the biblical garden down to size, and Eden’s saplings look very different in the hands of a range of contemporary artists. There’s something compelling about the diversity of interpretations in the show, as Eden’s perfection has never been nearly as interesting as the ways that it has been interpreted and misinterpreted.

Menachem Wecker is co-author, with Brandon Withrow, of “Consider No Evil: Two Faith Traditions and the Problem of Academic Freedom in Religious Higher Education,” forthcoming from Cascade Books.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO