Brewing Up Memories From Pushcart Days of Jewish Old Milwaukee

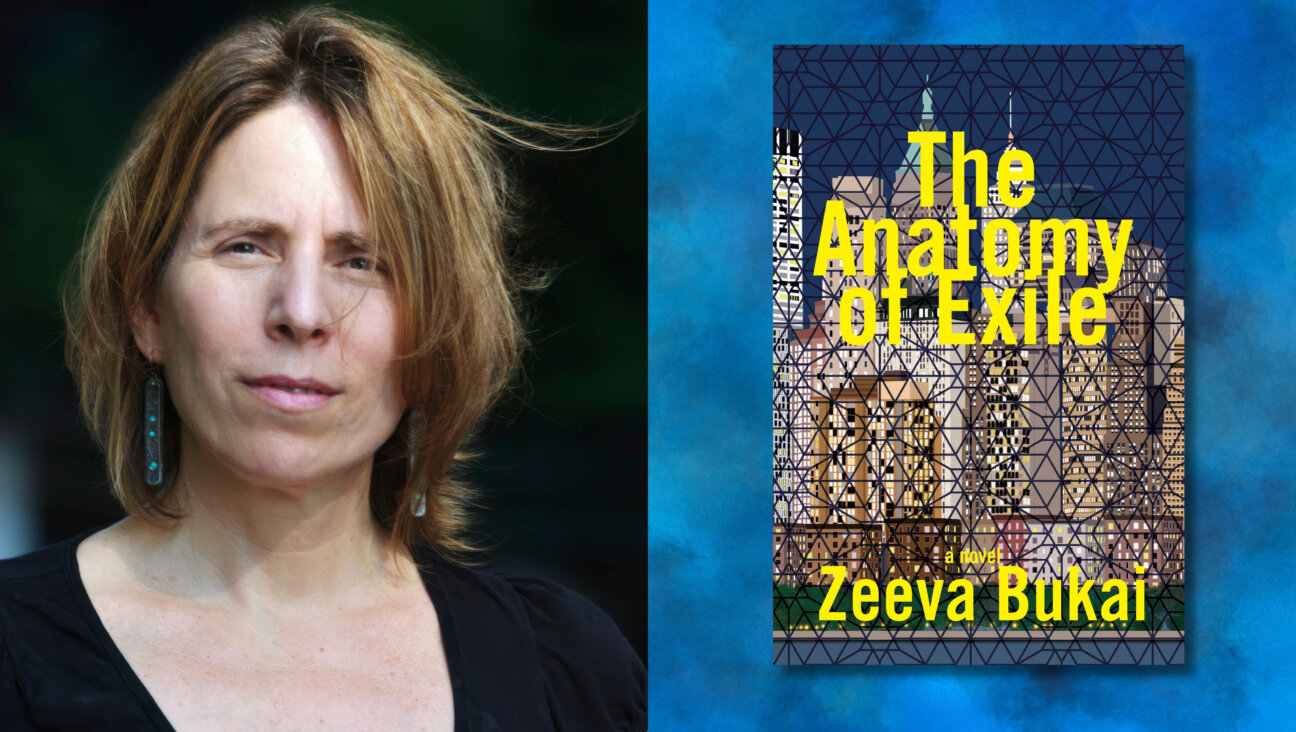

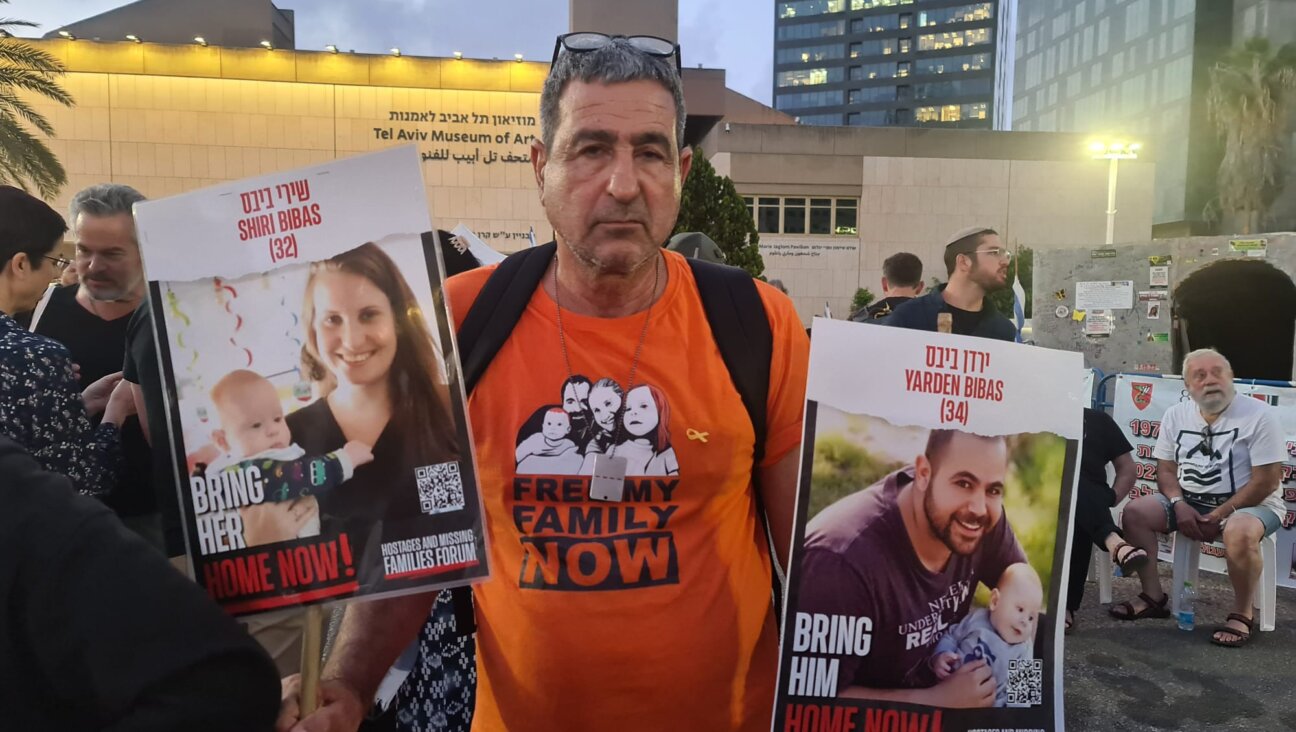

This One?s For You: In 1933, Leeb?s Tavern held a ?Death to Prohibition? celebration. Image by Courtesy of Jewish Museum Milwaukee

Approaching Milwaukee’s Helfaer Community Service Building, which Edward Durell Stone designed in 1973, it’s easy to be fooled by the windows. At first glance, the landscape-oriented building, nestled a block off Lake Michigan, resembles an enormous 10-by-3 wine box partition, with negative space peeking through the dividers. But however deceptive the highly reflective windows may be, the building turns out to be solid.

If the objects in the Jewish Museum Milwaukee’s mirrors are closer than they appear, its interior gallery space is smaller than one might assume. The exhibit “From Pushcarts to Professionals: The Evolution of Jewish Businesses in Milwaukee” (through December 1), which tells the story of 170 years of Jewish life in the city, occupies a single room, yet it features several gems that make it well worth a visit.

In a glass case alongside bottles of 3 Bears Grape Soda and Bon-Ton Sour Mix, and a Mug and Jug ashtray is a beer foam scraper that looks like a large, blunted butter knife. It takes some sleuthing to appreciate the full significance of the artifact.

On one of the wall panels in the exhibit, a photograph dated December 5, 1933, and titled “Death of Prohibition” shows more than two dozen people at Leeb’s Log Tavern, celebrating the ratification on that day of the 21st Amendment. Many of the men and some of the women assembled raise full beer glasses as they flank a casket fitted with a note: “Here lies the 18th amendment [Prohibition], died Dec. 5th 1933.” Set atop the coffer — between Jewish owners Max Leeb and Sam Tempkin — like tchotchkes on a mantel are a bottle of booze, a candlestick and the very same beer foam scraper.

Roberta Bloch, Leeb’s daughter, lent the scraper to the exhibit. She found it in a box of family materials that was labeled from the early 1930s. “Roberta is confident that the beer foam scraper pictured is the same one we now have on display,” said Molly Dubin, the Jewish Museum Milwaukee’s curator.

In the city of beer, Jews took to the brewing profession long before Maccabee and He’Brew. Leeb’s father-in-law, Max Gottlieb, owned another tavern, Gottlieb’s. It was located at 12th Street and Meinecke Avenue, about 2 miles northwest of Leeb’s location at Juneau Avenue and Third Street (now Dr. Martin Luther King Drive). Leeb, who changed his name from Gottlieb, later ran M&N Bar and Lounge, and his brother owned and ran Mug and Jug and later Layton Heights, a south side bar. Logoed ashtrays from M&N and Mug and Jug appear in the exhibit, although Layton Heights isn’t mentioned.

With Milwaukee’s large German immigrant population, taverns were goldmines. And when it came to outfitting those saloons with snacks to keep patrons thirsty, that, too, was a Jewish affair.

A framed July 15, 1934, issue of the Milwaukee Sentinel, which appears in the exhibit, tells of the rapid growth of popcorn sales in Milwaukee following the repeal of Prohibition. “To supply the taverns, clubs, cafes, and other beer dispensaries, about 6 tons of corn are popped and distributed weekly by some 15 ‘manufacturers,’” the articles states, singling out one of those popcorn men: Irving Solomon. Solomon’s setup, which operated about 4 miles northwest of Gottlieb’s, stocked some 400 beer-serving establishments, according to the article.

Dubin learned from Solomon’s daughter, Jane Chester, who lent the 1934 article, that the popcorn-monger hawked his wares to bar owners as a strategy for patron retention, and for keeping those patrons thirsty from the salt.

Jewish immigrants from Russia and Eastern Europe also gravitated toward other professions, such as peddling, scrap metal and shoemaking, that required little overhead. “Jews were involved with scrapping one way or another for hundreds of years back in Europe,” said Jonathan Pollack, a history instructor and the author of the chapter “Success From Scrap and Secondhand Goods: Jewish Businessmen in the Midwest, 1890–1930” in the 2012 book “Chosen Capital: The Jewish Encounter With American Capitalism.”

German Jewish immigrants to Milwaukee in the mid-19th century were peddlers, but they soon learned that there were better incentives to purchase scrap metals — particularly when much of the iron ore in the area had been mined. “People were much more receptive if they knocked on the door and said, ‘Hey. I noticed a rusting plow out in your field. Can I give you a couple of bucks for that and take it off your hands?’” Pollack said. “And people would say: ‘Oh that old thing? Here, let me help you get that out of here. Thank you for taking it.’”

“Scrap in some ways is like peddling in reverse,” added Pollack, who will deliver a lecture titled “Built on Scrap” at the museum in October. One aspect of his research has been the occupational diversity of early Jewish communities in the Midwest. When one researches who the presidents of early Zionist societies and synagogue boards were, one finds that they were all scrap dealers, Pollack said.

“If you look at old city directories and phonebooks and things like that, you’ll have a city the size of Madison that would have like 10 scrap dealers, all of whom were Jewish,” he added. “It really sticks out at a point that Madison had a very tiny Jewish community…. Everybody was in scrap.”

Jews certainly aren’t monopolizing scrap any longer, but my trip to Milwaukee suggests it’s fair to assume that beer will remain a staple of Jewish diets for the foreseeable future.

Menachem Wecker is a Chicago-based writer on art and religion. Find out more about him at http://menachemwecker.com or on Twitter, @mwecker.

index.php

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO