How To Train a Hebrew-Speaking Dog

Image by wikicommons

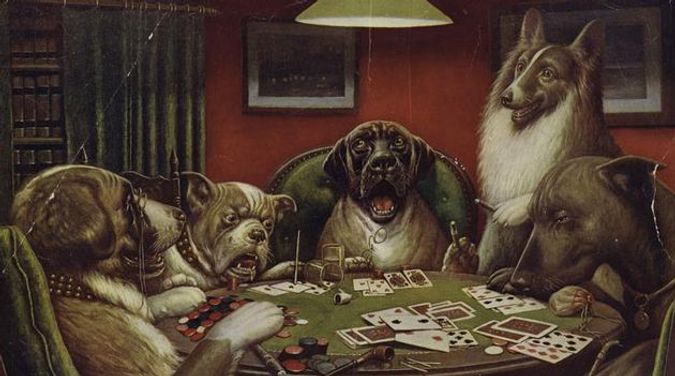

Like People: Some dogs take to sitting with a natural flair. Image by wikicommons

Cheryl Krushat writes:

“We are about to adopt a female puppy, to whom my son would like to teach Hebrew commands. My son was given the impression that Israeli search and rescue dog handlers he met while he was in the U.S. Army gave commands in one gender form, regardless of the dog’s sex — yet perhaps they used the infinitive. So, should I teach my female puppy shev, sh’vi, or lashevet?

“In addition, a Hebrew-speaking friend has told me that kalbá, the feminine form of kelev [dog], is not used for dogs, but rather for women of certain behavior. Would you then say ‘Good dog!’ to a female canine with kelev tov [using the masculine form of the adjective] or kelev tová [using the feminine form]?”

I don’t know any Israeli dog trainers to ask about this one, and I’m tempted to answer Ms. Krushat that, it being considerably harder to get Hebrew-speaking Israelis to follow orders than it is to get English-speaking Americans to do so, she should perhaps train her new puppy in English. For the benefit of readers who know no Hebrew, however, let me explain her dilemma.

Hebrew, like other Semitic languages, not only divides all nouns into grammatically masculine and feminine, but also does so with most forms of verbs. Thus if we take the verb “sit,” yashav, we get hu yoshev, “He is sitting”; hi yoshevet, “She is sitting”; anaḥnu yoshvim, “We are sitting” (if those sitting are male); anaḥnu yoshvot, “We are sitting” (if those sitting are female); etc. Imperative forms of verbs are gender specific, too, so that, as Ms. Krushat writes, “Sit!” to a male is shev and to a female, sh’vi.

All this is true of classical Hebrew. In contemporary Israeli Hebrew, some things have changed. On the one hand, these commands have been simplified. Whereas in classical Hebrew, for example, “Sit!” to a group of men is sh’vu and to a group of women, shevna, Israelis use sh’vu in both cases. Yet on the other hand, modern spoken Hebrew has — as again, Ms. Krushat points out — three ways of forming the imperative instead of one. “Sit!” can be not only shev or sh’vi, but also (using the future tense form for “You will sit”) teshev or teshvi, as well as (using the genderless infinitive form for “to sit”) lashevet.

Why this has happened is a complex story, having to do with both internal developments and the influence of European languages. The interesting thing is that each of these different forms of the imperative sometimes has a different shading. Shev can be a bit more peremptory, teshev can sound more diffident and lashevet, especially when said to a group, can have a somewhat impersonal tone that might be translated as, “You’re requested to sit.” This is not, though, an absolute rule. If you shout “lashevet,” you’ll sound a lot harsher than if you quietly say “shev” with a smile.

The differences are subtle — subtler, certainly, than can be grasped by a dog. From the perspective of a Hebrew lover, though, I would advise Ms. Krushat to say shev to her puppy if it’s a male and sh’vi if it’s a female. It’s more elegant than teshev and teshvi, and far more so than lashevet, which, despite having the advantage of genderlessness, is to my mind ugly Hebrew. (I can’t help hearing German sitzen sie behind it.) And although Israeli trainers facing a classroom of male and female dogs might address them all in the masculine (the trainer wouldn’t use the unisex sh’vu, because when the course is over, owners aren’t going to address their dogs in the plural), no native-born Israeli would say “shev” to a dog known to be female any more than he or she would say it to a female person.

Nor would an Israeli ever say kelev tová, attaching a feminine adjective to a masculine noun. Despite what Ms. Krushat was told by her friend, kalbá, the feminine form of kelev, is used all the time in Israeli Hebrew for female dogs. In this respect, it is unlike the word “bitch,” whose pejorative meaning in English has largely eliminated it from the vocabulary of pet owners. Perhaps Ms. Krushat’s friend was thinking of the Aramaic form of the word, klavta, which — pronounced klafte — definitely does refer in both Yiddish and contemporary Hebrew to an unpleasant or malicious woman. The word first appears in the form of kalbeta in the talmudic tractate of Rosh Hashanah, where there is a discussion of a verse in the book of Nehemiah that is generally translated, “And the king [Artaxerxes] said to me [Nehemiah], with the queen [Hebrew shegal] sitting at his side, “How long will you be gone and when will you return?’” The word shegal comes from the Hebrew verb shagal, “to copulate with,” and the renowned scholar Rav is quoted by the Talmud as remarking that it should be translated not as malketa, “queen,” but as kalbeta — that is, as the king’s “bitch” or sexual plaything.

That’s really more, though, than one can reasonably expect Ms. Krushat’s new puppy to understand.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected]

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO