Last Song of Hitler’s Favorite Crooner

Image by getty images

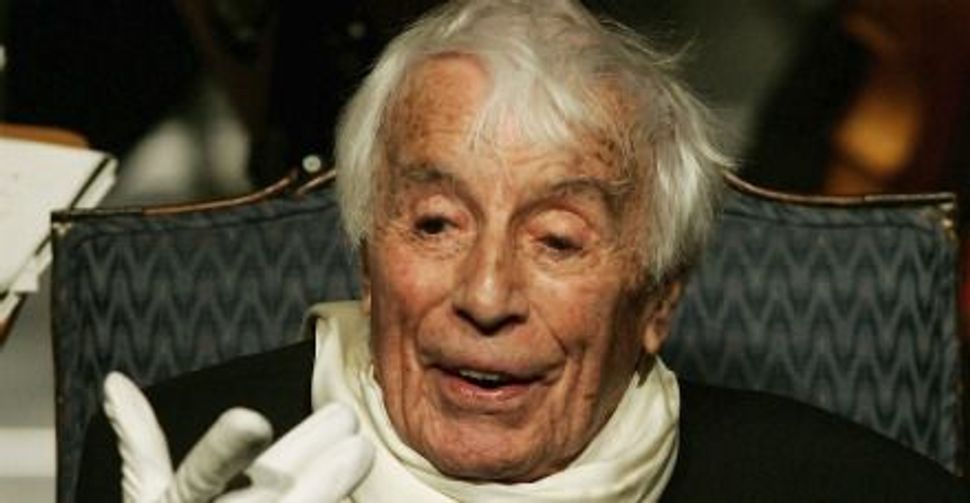

Dance With Devils: Singer Johannes Heesters, right, gets a guided tour of Dachau concentration camp from Nazi officers. Image by EPA

Right up until his death, on December 24 at age 108, Dutch-born singer and actor Johannes Heesters was still performing the songs that had made him famous and, in some circles, infamous.

Beloved and much honored in Germany and Austria for a steady stream of stage, screen and television roles and recordings, Heesters owed his long career to the man who made him a star — Adolf Hitler. No one disputed Heesters’s talent as a charmer, but, at least outside of the German-speaking world, he never shook free of the sulfurous stench of his deal with the devil.

Having eagerly lent his talents to the Nazis, and as a result been the eager recipient of more benefits from the Third Reich than any other non-German artist, Heesters remained grateful for the patronage. As late as 2008 in a TV interview, he called Hitler “a great guy” and he brushed aside the immediate correction from his much-younger wife that Hitler was “the worst person in the world” by explaining, “I know, Doll, but he was good to me!”

Image by getty images

Blame it on “The Merry Widow.” Adolf Hitler was smitten with Franz Lehár’s operetta, with its sentimental tunes, satiric plot about “Vaterland” politics, women’s emancipation, money and love — never mind its Jewish authors, Leo Stein and Viktor Léon. When Munich’s Gärtnerplatztheater announced a production in 1938, Hitler had to have a box seat. The young Dutch singer making his Munich debut as Danilo, the romantic male lead, was Heesters. As recounted in “Der Herr im Frack” (“The Guy in Tails”), the detailed biography of Heesters by Jürgen Trimborn (who also wrote the definitive biography of another long-lived Nazi artist, Leni Riefenstahl), Heesters was astonished to see Hitler showing up to moon over his performances night after night.

Trimborn quotes Heesters claiming in a 1998 interview for the daily newspaper Die Welt that he “never gave a ‘Sieg heil’ salute,” because he found it “so unbecoming.” On the contrary, it was Hitler who kissed Heesters’s hands. “I was flabbergasted… and walked away proud as a peacock.” Hitler personally commanded (or rather “invited”) Heesters and the rest of the Gärtnerplatztheater company to return to Munich to perform “Merry Widow” as the highlight of the infamous, annual state- and city-sponsored propagandizing festival Tag der Deutschen Kunst the following July. Bear in mind that Munich’s magnificent main synagogue, solely because its existence “offended” this festival, was demolished in preparation for this event — so, despite its Jewish and Hungarian provenance, “Merry Widow” thereby became accepted officially as the highest sort of “holy German” art.

Trimborn quotes Hitler’s housekeeper recalling him emulating Heesters in the role, complete with top hat and tails, scarf tossed over his shoulder, asking: “What do you say? Am I no Danilo?” The enthusiasm of the Führer made Heesters and “Merry Widow” the biggest hit in the Third Reich. Productions proliferated, becoming ever more grandiose with generous state subsidies and promotion. Richard Strauss became so crazed with jealousy that it’s likely (according to Trimborn) he tried to incite Nazi thugs to kill Lehár.

Albert Speer recalled that the first thing Hitler did to celebrate the Anschluss was ask Martin Bormann to play the recording of “Merry Widow.” Bormann dutifully asked which recording — the production Lehár himself had conducted in Berlin in his honor or Heesters with the Gärtnerplatztheater artists? For Hitler, Heesters’s was “10% better!” Hitler’s “Merry Widow” mania only increased, and in the final years of the war, 1943 and ’44, Hitler drove everyone else crazy in his Wolf’s Lair by listening only to Heesters’s recording of “Merry Widow” over and over again.

The Third Reich’s obsession with Heesters and “Merry Widow” has left a permanent mark on music history: Shostakovich, when composing his “Leningrad Symphony” during the siege, decided to represent the German invaders with a fragment from Heester’s signature “Merry Widow” song. Béla Bartók in exile in New York, hearing the dramatic Allied Radio broadcast of this symphony while the siege was still going on, famously decided to mock this theme in his “Concerto for Orchestra,” even having the orchestra imitate laughing at it.

Hitler’s backing made Heesters one of the highest-paid, best-known artists in Nazi Germany. The singer acknowledged to the Süddeutscher Zeitung that “it rained prizes and awards.” Trimborn explains that all such “regime conforming” artists were so essential to keeping the Nazi movement going that not only did they get a 40% break in taxes, but they also could expect to receive cars, “Aryanized” villas or additional secret gifts. In exchange, they willingly helped the regime in numerous ways.

For example, Heesters performed at Dachau in May 1941 to boost the morale of the SS officers there. When this was exposed after the war, Heesters first claimed that it never happened and that he did not even know anything about Dachau (despite several of his Gärtnerplatztheater colleagues having been sent there in the roundups of Jews and political “undesirables”). Later, after a photo surfaced of him swanning at Dachau in the admiring company of SS officers, he switched his story, recalling how marvelously the prisoner-musicians played when they accompanied his colleagues. But he adamantly insisted that he himself had not sung for the SS there. Eyewitnesses then stepped forward to contradict him. Two years ago, a judge dismissed a slander lawsuit that Heesters had lodged against a historian about this, on the grounds that details could no longer be determined with certainty.

The same egregious, enabling opportunism infected Lehár himself, even though his reputation was secure internationally and he was already a millionaire. Although his wife was Jewish and therefore at risk, Lehár couldn’t bring himself to abandon his lavish lifestyle in Austria and the wildly lucrative “Merry Widow” royalties in the Third Reich productions. His wife had to convert and, as a precaution in case of arrest, carry a vial of poison with her until the end of the war — even though the Hitler connection allowed her to be officially designated an “Honorary Aryan.” Even with this status, however, the Gestapo came for her at the couple’s home, in Bad Ischl. “If I hadn’t happened to be at home, I would never have seen my wife again,” Lehár later told Allied liberators. But since he was home, he had the Gestapo men call the local gauleiter, who arranged for her to remain under “house arrest” in her own home for the remainder of the war.

After the war, the Americans let Lehár off the hook, as star-struck liberators preferred to have their pictures taken with the famous composer rather than ask questions about his relationship with Hitler, or why he defended himself in a lawsuit in 1938 by denouncing the plaintiffs as Jews to the Berlin authorities, or why he dedicated compositions to Hitler and also to Mussolini and partied with them in grand style despite knowing they were responsible for the gruesome deaths of several of his collaborators. Lehár, Trimborn adds, pretended — “like most Germans” — that he had nothing to do with the Nazis: “No politics, please…. We don’t want to talk about it. Politics is dirty, and I don’t like to talk about dirty things…. My conscience is clear. My ‘Merry Widow’ was Hitler’s favorite operetta. That’s not my fault, right?”

Unlike Lehár, who died in 1948, Heesters kept working as a major star after the war, at least in Germany and Austria. His career lasted 92 of his 108 years, and he played Danilo 1,600 times. Yet it always rankled him that his native Holland regarded him as a traitor and would have nothing to do with him. In 1964, he made the astonishingly blockheaded choice of vehicle to attempt a return there: the anti-Nazi Captain Georg von Trapp in a production of “The Sound of Music.” He was hooted off the stage. Only in 2008 did he succeed in giving a single recital, in a small hall on the Dutch border, amid many protests. In spring 2011, when Chancellor Angela Merkel hosted a state dinner for Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands, Heesters was invited as one of the most prominent Dutchmen in Germany. When the Dutch saw his name on the list, however, they immediately insisted he be disinvited. He will not be missed.

Raphael Mostel is a composer based in New York City. He frequently writes for the Forward and other publications.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO