Jews Who Died Fighting in Red Army

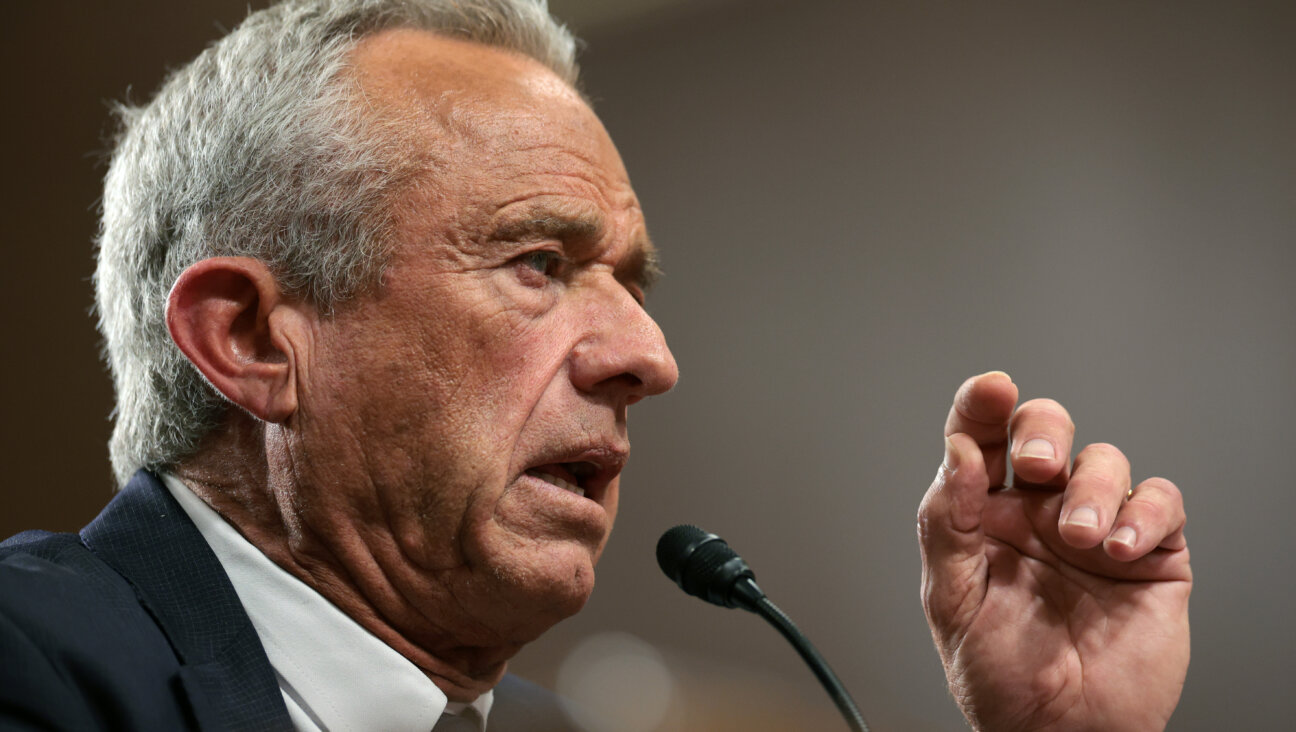

Image by courtesy of the blavatnik archive

Occupy Reichstag: Victorious Soviet troops pose outside the conquered seat of Nazi power in Berlin. Image by courtesy of the blavatnik archive

On May 9, 1995 — 50 years after the end of World War II — I stood among a celebratory crowd in a provincial Russian town and glanced over to see a war veteran pointedly scoop a palmful of water out of a puddle.

The veteran drank as if it were the finest water he had ever tasted. And when he finished, he fixed me with a look that was both joyous and defiant.

It is probably the oddest toast I have ever seen. Yet I had all but forgotten about it until recently, when I was standing in front of an exhibition about Russian-speaking Jewish veterans: “Lives of the Great Patriotic War: The Untold Stories of Soviet Jewish Soldiers in the Red Army During WWII.”

The Great Patriotic War is the name the Soviet Union gave to its bloody encounter with Germany, which began with the Nazi invasion in 1941. Seventy years later, the staggering numbers of dead and wounded are still being revised. According to this exhibition, 30 million Soviet citizens either volunteered or were conscripted into the Red Army. By war’s end, about 26 million people were dead and tens of millions more were wounded. Towns were destroyed, homes obliterated, entire families wiped out.

Of an estimated 500,000 Jews who served in the Red Army, only about 300,000 returned.

“The thing about these soldiers is that while they were fighting at the front, so many of them lost most of their families in the Holocaust,” said Julie Chervinsky, director of the Blavatnik Archive Foundation, which organized the exhibition.

Chervinksy said there has long been a stereotype in Russia that Jews played no role in the war. They were either dismissively said to have “fought the war in Tashkent” — about 1 million Jews spent the war in the relative safety of Central Asia — or were slaughtered in the Holocaust, which claimed about 3 million lives on Soviet territory.

“We realized there is a very important story about Jewish veterans that has not really been addressed by Holocaust studies,” Chervinsky said.

The Blavatnik Archive began collecting oral histories of Jewish veterans in 2006. It has amassed more than 1,000 video interviews from 10 countries and collected and digitally archived photographs and letters.

At first glance, the exhibition, which presents a fraction of these stories, seems overwhelming. About a dozen large frames line the one-room Weill Art Gallery. Most contain photographs of the veterans alongside densely packed text.

The veterans’ stories are well worth the concentration it takes to explore the exhibition. But they are conveyed most accessibly by a 15-minute video of interview snippets that loops on a television screen set up on a table next to a wall.

In the film, Vladimir Ilyich Nemets recalls seeing cotton fly out of the back of the coats of the soldiers running in front of him as the men were gunned down. Dora Motelevna Nemirovskaya recalls the “tchok-tchok-tchok” of sniper fire exploding around her as she struggled to bandage a gruesome stomach wound.

Although anti-Semitism was rare in the trenches, Chervinsky said that many Jewish soldiers felt they had to fight harder and act braver “so no one would say, ‘He’s a Jewish coward.’” She said Jewish veterans also recounted how they had “an extra score to settle with Hitler” after they found out about the Holocaust.

But for the most part, Judaism played a secondary role to the veterans’ identities as Soviet citizens. Often in the exhibition, the most striking elements of their stories are not the Jewish ones but the universal ones — the senselessness and randomness of war.

On a wall panel, Ilan Yakovlevich Palat recalls how, after being wounded in the ankle outside Kharkov, he was dragged off the battlefield. His comrade laid him out in a house and hung Palat’s boot by a window to alert passersby that someone was inside. In the early hours of the morning, Palat heard someone approach.

“I got my pistol ready, two cartridges: One bullet for him, the second for myself,” Palat recalled.

The stranger turned out to be a local woman who put Palat on the back of a cart and took him to the nearest field hospital.

Palat, who came from the Soviet Jewish region of Birobidzhan, said: “Of the 44 [of] us, only three came back. One returned without his left leg, another without his right arm and I came back on crutches.”

And so the exhibition continues, with a succession of gripping, firsthand accounts — of treachery and atrocities, of small acts of kindness and stirring examples of courage, of camaraderie and terror.

Each one deserves mention. But Semeon Grigorevich Shpiegel’s story is the one that reminded me of the veteran and the puddle. He volunteered for the Red Army in May 1942 and, as with all the exhibition’s tales, the small details of Shpiegel’s experience illustrate the widespread hardships of daily life.

At 19, Shpiegel was dispatched to Stalingrad, where he fought as part of a mortar unit in one of the cruelest and bloodiest battles in history.

“We crossed the river on the 27th of September,” Shpiegel recounted. “We had to get our water from the Volga and carry it in mess tins…. We drank water from the puddles. Drank water from the buckets that were standing next to houses, rainwater. The water was covered with mold. But we were thirsty and so we drank it.”

“Lives of the Great Patriotic War: The Untold Stories of Soviet Jewish Soldiers in the Red Army During WWII,” runs at the Weill Art Gallery, 92nd Street Y, until December 6. Forward publisher Sam Norich will moderate a panel about Jews in the Red Army on November 22 at the 92nd Street Y.

Paul Berger is a staff writer for the Forward.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO