A Queen Honored, a King and a Jester Premiered

Image by Courtesy of Moscow Film Festival

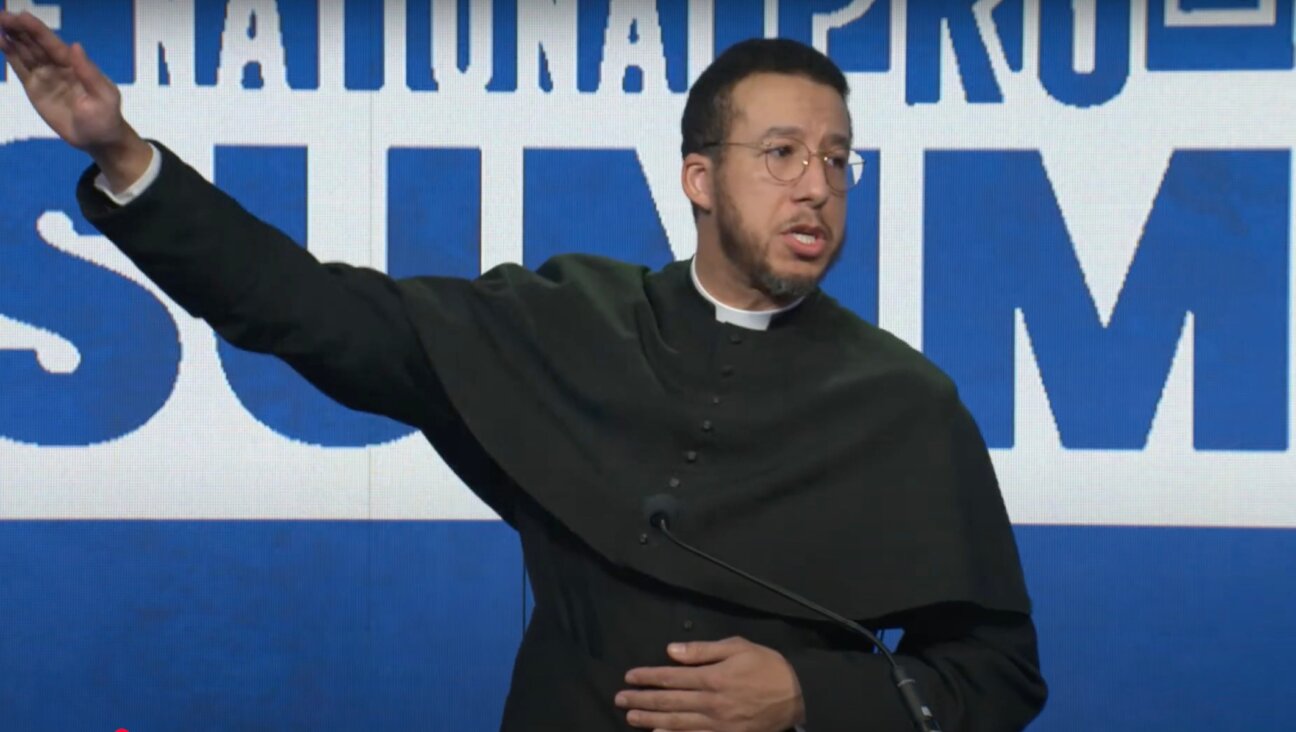

He Played the Part: Mark Donskoy in his 1926 film ?The Prostitute.? Image by Courtesy of Moscow Film Festival

The offerings of the 33rd Moscow International Film Festival, which ended earlier in July, were like the dishes on a dinner table in a hospitable Russian house: generously overflowing, but served in no apparent logical order. It was no surprise to those invited, then, that some of the films in the festival’s many programs and competitions, ranging from grand gala premieres to fringe art house projects, had a particularly Jewish flavor.

Among the films in the main competition were two Holocaust movies — a Hungarian-Romanian co-production called “Retrace,” by Judit Elek, and a Polish film, “Joanna,” by Feliks Falk. Both deal with Jewish children who were saved by local gentiles. But what a huge difference: “Retrace” recycles trite images predictable to the last black-and-white flashback, while “Joanna” is a beautifully shot, nuanced story of a young Polish woman harboring a Jewish child.

Events of the Holocaust also provide the background for John Madden’s spy thriller, “The Debt,” a remake of the 2007 Israeli film. Rachel (Helen Mirren) and two other aging Mossad agents have been venerated for decades in their country after tracking down a Nazi war criminal in 1966. They discover that the criminal is still at large. In Moscow, Mirren’s powerful acting was an appropriate excuse to present her with a special prize for her outstanding career achievements.

My personal favorite was “Mark Donskoy. The King and the Jester,” a Russian documentary about the great Soviet director. Written by the director’s son, Aleksandr Donskoy, and directed by Aleksandr Brun’kovskiy, “King and Jester” weaves together archival footage, excerpts from Donskoy’s own films, interviews with family members, and comments from other filmmakers and critics. The documentary paints a portrait of a complex and contradictory figure.

Mark Donskoy (1901–1981) was “the king” because he won several Stalin Prizes, the highest Soviet mark of achievement. But he was also “the Jester” because, at the time, playing a village idiot was a survival strategy. As the documentary points out, however, the mask grew into his face. He was a prankster and a master of the practical joke (from the first row in the Moscow film theater, he used to stick out his foot to trip those who came in late). It is with mixed feelings that he is recalled by his former crew and cast members.

The great director had an unpredictable temper and could explode on set. But for the regime, his reputation as an “emotional” artist served as an excuse: “The Jester” was allowed a greater freedom. Indeed, it is amazing to see how often Donskoy’s films, even the most serious ones, rely on the trope of the carnival. Nearly each one of them features playful scenes taking place at the fairs and folk festivals, with musicians, clowns, bells and bears. A generous montage of those included in the documentary gives an insight into the filmmaker’s own burlesque character.

The contradictions do not end there. Donskoy came from a modest background — a son to a poor Jewish family from Odessa — but he became the quintessential Soviet image maker. Most famously, Donskoy’s trilogy of films in the 1930s, adapting Maxim Gorky’s autobiography with the blessing of the venerated writer, brought him the recognition of the Soviet establishment.

Donskoy’s war-time drama, “The Rainbow,” a tragic story of a Ukrainian woman under the German occupation, won not only a Stalin Prize, but also recognition of American critics. Franklin Roosevelt loved the film so much that he was able to watch it without translation. In archival footage, Donskoy proudly cites Roosevelt’s letter written to him in 1943: “Soviets are fighting not only for Russian mothers and children but also for American mothers and children.”

After the great success of “The Rainbow,” Donskoy made the first-ever — in 1945 — film about the Holocaust, “The Unvanquished,” starring the great Soviet-Yiddish actor Veniamin Zuskin. Donskoy was not part of the Soviet Yiddish cultural establishment, nor did he even identify publicly with anything Jewish, and yet, in his feature he included a scene of a mass execution of Jews. He filmed it on location, in Babi Yar, in Kiev, Ukraine, the place where more than 30,000 Jews were killed. Babi Yar later came to symbolize the Holocaust in the Soviet Union.

An excerpt from “The Unvanquished” included in the documentary shows a heart-rending scene. The camera pans over Germans crowding Jews into the ravine, closing up on children, women and the elderly. As the Germans point their guns, Jews huddle together below, silent and motionless. About to be murdered, a bearded man who looks like a biblical patriarch clutches a young boy. This is little Aleksandr Donskoy. The director cast his own son, then 7 years old, in this scene, showing how closely he identified with the tragedy. Amazingly, the film was released on Soviet screens — approved by Stalin himself, who, as a self-appointed producer and censor of Soviet movies, was involved in every decision.

Soon after that, Stalin had a change of heart, and the Soviet regime became vehemently anti-Semitic. Jewish culture was destroyed; memory of the Holocaust was erased; Solomon Mikhoels and Veniamin Zuskin, along with other Yiddish writers and artists, were killed. Donskoy himself managed to survive those dark times reasonably well. Although he was fired from the film studio in Moscow, he was sent not to a gulag, but to a film studio in Kiev, where he was able to continue his work. There he made “The Horse That Cried,” a beautifully shot love story of two escaped serfs in 18th-century Ukraine. Essentially, though, it was a film about freedom, a bold gesture in the post-Stalin Soviet Union.

Donskoy eventually returned to Moscow and continued to make films there, directing several biopics about Lenin, but gradually he became less and less relevant. Today, Donskoy is all but forgotten at home, though in Europe he is remembered as a precursor of Italian neorealism and French “new wave.” Such important directors as Milos Forman and Giuseppe De Santis, shown in the documentary, list Donskoy among their main influences.

This is the mixed legacy of Mark Donskoy — a king and a fool, a “non-Jewish Jew” and a “rootless cosmopolitan.” It is a legacy that in many ways encapsulates the Soviet Jewish experience of the past century. How appropriate to have his film biography premiere in Moscow.

Olga Gershenson is associate professor of Judaic and Near Eastern studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. She is writing a book about the Holocaust in Soviet films.

Correction Appended: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Mark Donskoy’s film “The Rainbow” won an Academy Award. While the film received American acclaim, it did not win an Oscar, which had no Foreign Language category at that time.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO