Language Educators Rethink Their Hebrew Lessons

RINGVALD: ?Being a teacher of Hebrew language is a very specialized thing.?

Rachel Jackson doesn’t remember learning Hebrew at the Jewish Community Day School, where she spent kindergarten through eighth grade, but something must have stuck: She’s now among the top Hebrew-language students at her Jewish high school.

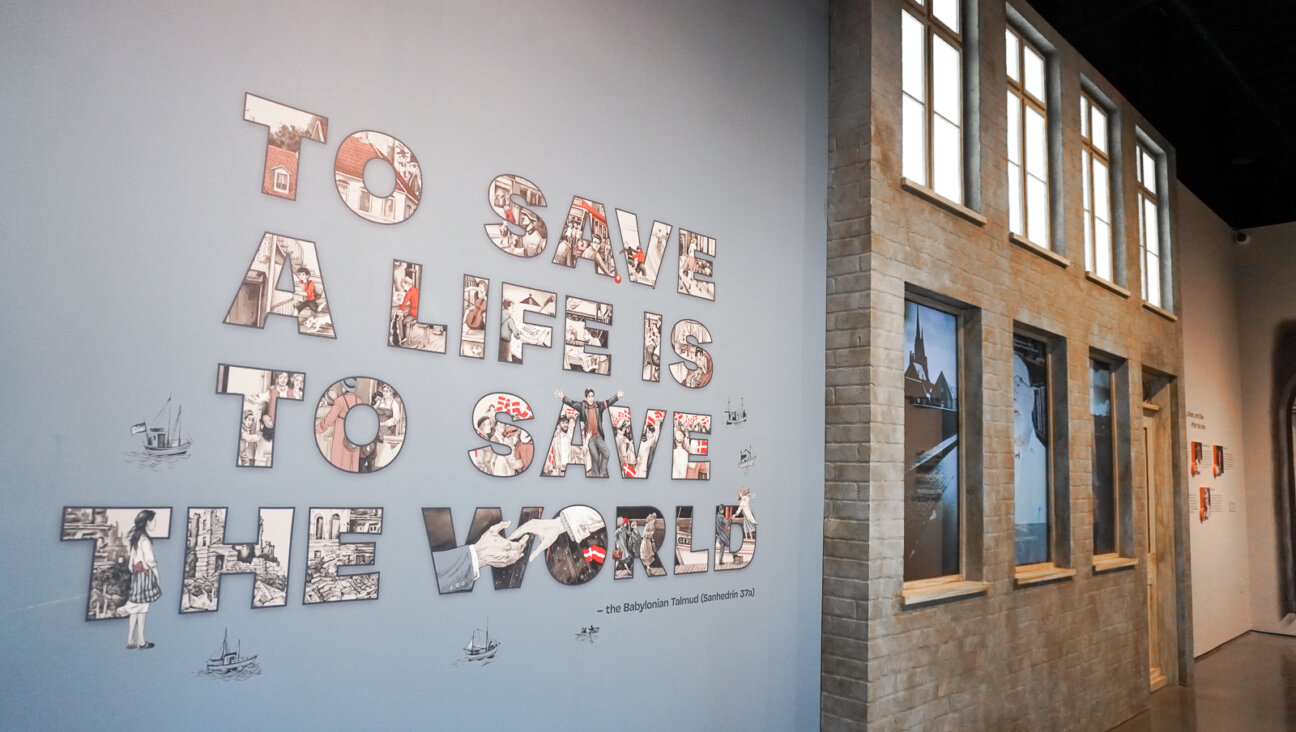

TAKING NOTE: JCDS fifth grader Sam Sano writes in his notebook ? in Hebrew

RINGVALD: ?Being a teacher of Hebrew language is a very specialized thing.?

“Things I learned at JCDS, I don’t remember learning, because they seemed to come naturally,” Jackson said. Perhaps that’s not surprising at a school where students learn the language by studying Israeli bumper stickers, watching Israeli TV shows during lunch and performing in dance classes conducted entirely in Hebrew.

JCDS is the flagship school of a new organization called Hebrew at the Center: The Center for the Advancement of Hebrew Teaching and Learning. Based in Watertown, Mass., just outside Boston, HATC is dedicated to professionalizing the field of Hebrew-Language education in kindergarten through 12th grade. For Jewish day schools and other institutions emphasizing Hebrew, HATC offers a range of services, from helping administrators develop strategic plans to imparting to teachers the intricacies of second-language acquisition.

“Being a teacher of Hebrew language is a very specialized thing,” said Brandeis University professor and Hebrew-language education innovator Vardit Ringvald, whose research informs HATC. “You don’t learn how to do it just by taking one or two courses in teaching Hebrew. It is a specialized subset of Jewish education and requires its own set of knowledge and tools.”

HATC’s debut comes at a time when there is widespread discontent with student achievement in learning Hebrew at Jewish day schools. There’s no data proving whether that discontent is merited. “But,” said Harvey Shapiro, associate professor of Jewish education at Hebrew College in Newton, Mass., “there is an anecdotal, intuitive sense prevailing that there’s an across-the-board phenomenon of underachieving in Hebrew-language education.”

And it’s not just Jewish schools. Compared with Europe and elsewhere, America has been stubbornly monolingual. Mary Abbott, education director for the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, attributes this to the country’s historic geographical isolation and to its dominance as a major economic power: Americans generally haven’t needed to learn other languages. In contrast, students in ulpanim — crash courses in Hebrew for immigrants to Israel —become functional in a matter of months, because they are motivated to join a Hebrew-speaking society and are immersed in Hebrew outside the classroom.

ACTFL has pioneered an approach to language education known as “proficiency,” which emphasizes students’ ability to use a language, to speak, listen, read and write. Under the proficiency approach, students spend significantly more class time learning to communicate than on conjugating verbs.

Typically, professional development for Hebrew-language teachers has been limited to training in a given curriculum. HATC departs from this practice, aiming to transform teachers into independent, critical users and developers of curriculum. Through workshops, mentoring and teamwork, HATC trains teachers to set language-proficiency goals for their students; to understand the cognitive process of second-language acquisition; to perform “assessments”— that is, to be able to pinpoint each child’s skill level at any given moment; to create lessons and curricula tailored to the children’s interests; to select primary sources — Hebrew poetry, music, stories, even advertisements and blogs — as teaching materials, and to plan further action based on students’ proficiencies.

Hebrew at HATC “creates an unbiased and critically informed assessment of what’s going on with teaching and learning Hebrew in a school, then says to the institution: ‘Ask yourselves, what are your goals? Are you meeting them? What are your shortcomings? What curriculum development, what teacher development, do you need to do better? What issues do you need to address?’ Then they offer the support requisite to make those improvements,” said Marc N. Kramer, executive director of Ravsak, a national network of Jewish community day schools that is based in New York City.

HATC developed from more than 15 years of research and practice. When founding JCDS, Ringvald and educator Arnee Winshall were influenced by research showing the educational benefits of learning a foreign language, and by their belief that Hebrew is key to Jewish identity: to connect to Israel, to Jewish culture and to Jewish texts. When it opened in 1995, JCDS introduced some teaching innovations, but Winshall and her colleagues weren’t satisfied. “We noticed our teachers were wonderful and enthusiastic, but knew nothing about language acquisition or Hebrew teaching, even if they were native speakers,” Winshall said. “There was good curriculum available, and we sent our teachers to learn the curriculum. But the curriculum was one-size-fits-all. You were locked into their topics. What if your school had other priorities?”

Ringvald, meanwhile, was studying language acquisition, and she helped develop ACTFL proficiency guidelines for Hebrew. JCDS received a five-year, $250,000 grant from The Covenant Foundation, enabling Ringvald and Sharona Givol, JCDS’s Hebrew coordinator, to pioneer the system of teacher training and Hebrew instruction that JCDS uses now. HATC branched off from JCDS to help other schools improve their Hebrew programs.

JCDS teacher Michal Baruch, an educator for 26 years, is working toward her ACTFL certification. She says she loves this approach to teaching Hebrew. “As a teacher, you can change and do whatever you want, as long as you stick to the goals,” Baruch said. For one project, she gave her students the choice of doing a fashion show or designing a store window. “One kid designed a store window and wrote a song in Hebrew rhyme about it. Now, the whole school sings the song!” she said.

Students find that Hebrew connects them directly with people and tradition. “I like being able to have a conversation with an Israeli in the language that they know,” said Adina Poras, a recent JCDS graduate. “It’s easier to use the prayer book, and during Jewish studies, it is a lot easier,” added Poras, who prefers to study Jewish texts in the original Hebrew.

The HATC approach expects a lot from teachers. Tamar Warburg, mother of two JCDS graduates, said, “To do this way of teaching Hebrew, the teachers must be very bright, creative, flexible and motivated.” Some teachers are resistant at first. Liat Kadosh, Hebrew-language director of the Atlanta-based Epstein School, recalls teachers’ reactions when she introduced HATC workshops in her school. “My name was ‘Proficiency,’ not ‘Liat,’ she said. But over three years, her teachers have developed 11 new Hebrew-language units. “The beneficiaries are our students,” Kadosh said. “Our materials are not fancy compared to what you can buy, but our results are above and beyond.”

Using a six-figure gift from an anonymous donor, HATC plans to bring on eight to 10 schools as clients this year. It takes about three years for a school to internalize HATC’s methods, according to the organization’s executive director, Lesley Litman. Costs per school vary widely, but training a single teacher for ACTFL certification costs roughly $1,000.

HATC also plans to become a research center and an online clearinghouse of teaching resources. “We don’t claim to have all the answers,” Litman said. “If we find something better than the proficiency approach, we’ll change to that.”

While acknowledging that HATC is making needed and constructive changes in Hebrew-language education, many say that more must be done. This is a field in which barely any data exists and professional conferences are unheard of. Rabbi Joshua Elkin, executive director of the Partnership for Excellence in Jewish Education, said: “We do not have a sufficient number of initiatives going on in North America to galvanize the groundswell we need to strengthen Hebrew-language proficiency and acquisition. Part of having a robust field is having constructive dialogue about different approaches.”

Perhaps the launch of HATC will send out some ripples.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO