Circumcision: The Box Set

Image by Courtesy of the American Jewish Historical Society

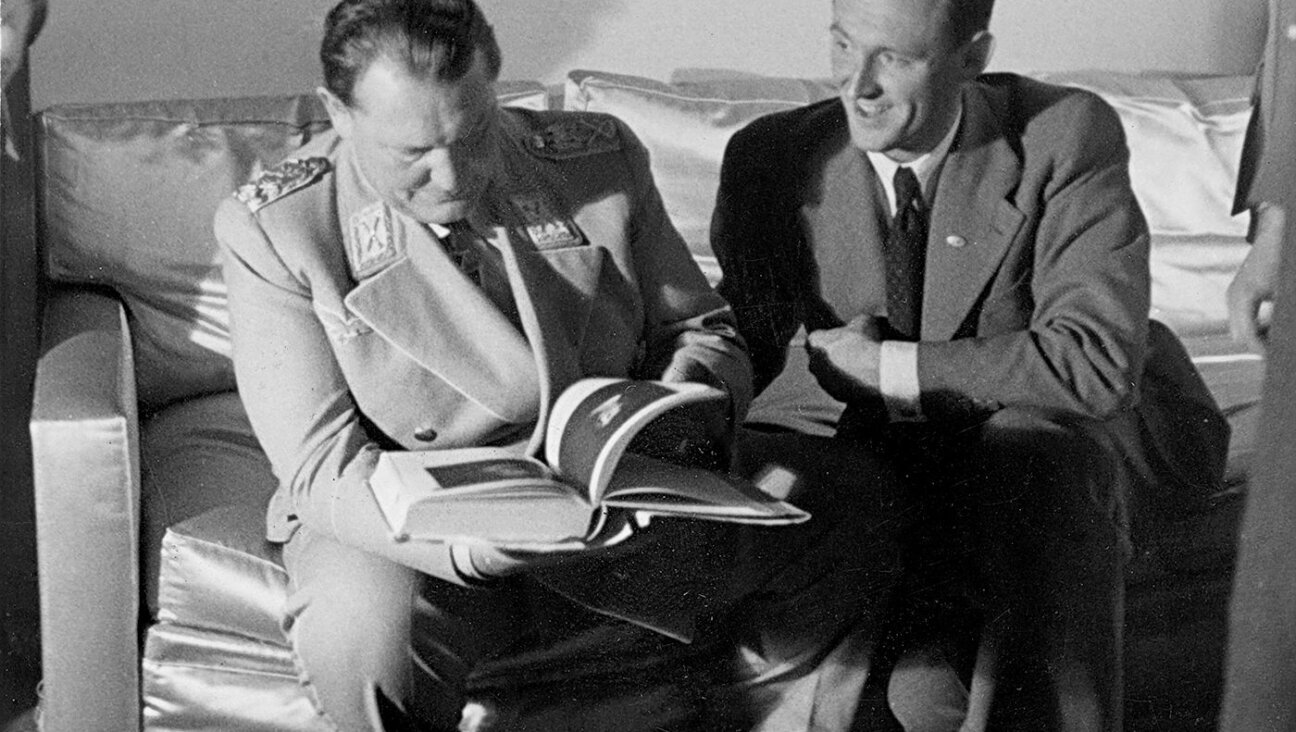

George Washington’s letter to the Jews of Newport, R.I., has occasioned a fair amount of discussion of late. When it comes to our colonial patrimony or birthright, though, the Seixas family circumcision set should, by rights, give the presidential missive a run for its money. From the mid-18th century through the early years of the 1800s, the ritual implements used to perform a brit milah passed between two brothers, Gershom Mendes Seixas and Moses Mendes Seixas, who served as mohelim in their respective communities of New York and Newport. (To gild the lily, Moses Mendes Seixas also happened to be among those with whom George Washington communicated.)

Tools of Service: Though primarily merchants, Gershom and Moses Seixas also performed circumcisions. In the small Jewish population in colonial America, learned laymen provided religious leadership and communal services. Image by Courtesy of the American Jewish Historical Society

Finely wrought and clad in silver, the implements, which are now a part of the holdings of the American Jewish Historical Society, are lovely to behold, as is the wooden box, covered in sturdy cowhide, that contains them. All the same, what draws us to these objects when they’re on display, as they often are, is not their aesthetic appeal, but the way in which they bear witness to the tenacity of Jewish tradition and ritual. As Aaron Lopez, a colonial Jew of Newport, roundly declared in a 1767 letter to a friend, circumcision is the “Covenant which happily Characterize us a peculiar Flock.”

In Lopez’s time and country, this “slight operation,” as another authority put it, was accorded respect, especially given its biblical antecedents. But today, as anyone who has picked up a newspaper in the past month is well aware, circumcision is an increasingly controversial — and politicized — phenomenon. Between the two extremes, there lies a fascinating and often overlooked history, one in which circumcision moved into the mainstream of American life from the margins.

By the tail end of the 19th century, circumcision had become a standard medical procedure and, arguably, one of the most frequently performed surgeries in the United States. In striking contrast to its hotly contested and fiercely debated status in the Old World, where circumcision was often attributed to the unbridled appetite for blood and to a penchant for cruelty that allegedly characterized the Jews, the ancient ritual practice was heralded in the New World as a social good: a form of preventive medicine. “Moses was a good sanitarian,” Dr. Norman H. Chapman, a professor of nervous and mental disease at the University of Kansas, cheered in 1882, adding that “if circumcision was more generally practiced at the present day, I believe that we would hear far less of the pollutions and indiscretions of youth.”

In the years that followed, growing numbers of medical men took Chapman’s advice to heart and advocated for “universal circumcision,” claiming that it prevented disease, suppressed masturbation and neutralized irritability. Ironically enough, given the prominence of anti-circumcision sentiment in contemporary California, one of the leading champions of the practice, Peter Charles Remondino, was a high-ranking official of the California Medical Society who attributed all manner of illness to the uncircumcised member. “Man’s whole life is subject to the capricious dispensations and whims of this Job’s-comforts-dispensing enemy of man,” he wrote dramatically, insisting that all it took to set things right was the removal of the foreskin.

To bolster his claims, Remondino and other champions of circumcision pointed to the Jews, whose surprisingly low mortality rate and reduced incidence of both cancer and syphilis seemed to argue for circumcision as a “sensible” and healthy proposition. For centuries, the public imagination had associated these diseases, along with the Jews, with dirtiness, a canard given a new lease on life by the overcrowded tenement conditions in which so many immigrant Jews lived. Under the circumstances, the Jews’ physical resilience was rather baffling. To get to the bottom of this puzzle, statisticians and public health officials in the United States launched detailed demographic studies that, invariably, yielded the conclusion that distinctive ritual practices, from brit milah to kashrut, kept the Jews in good shape. Circumcision, Remondino allowed, “is the real cause of the differences in longevity and faculty for enjoyment of life that the Hebrew enjoys in contrast to his Christian brother.”

The stamp of approval that the medical community placed on circumcision was not without its drawbacks. By transforming a ritual into a procedure, the nation’s doctors affected not only its meaning, let alone its raison d’être, but also undermined the authority of those who had traditionally performed it: The mohel gave way to the medical doctor. A function of the growing professionalism of modern America, in which amateurs from all walks of life were increasingly supplanted by those with formal training, the medicalization of circumcision also grew out of heightened concern about the risks posed by those ignorant of the “modern principles of asepsis,” or so explained Dr. Abraham Wolbarst, writing in the pages of the Journal of The American Medical Association in 1914.

Many American Jews took great pride in the ways in which modern science both ratified and secured the value of age-old Jewish rituals. “Judaism has made religion the handmaid of science,” Dr. Maurice Fishberg wrote approvingly. The author of, among other things, “The Health and Sanitation of the Immigrant Jewish Population of New York,” he noted that Judaism “has utilized piety for the preservation of health.” Nicely put, Fishberg’s assessment, along with the views of his medical colleagues, placed hygiene ahead of covenant and highlighted the universal at the expense of the particular. It made for an unusually compelling argument way back when. But does it hold up today? I, for one, can’t help but wonder whether defining the ancient rite of circumcision as “sensible” loses something in translation.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO