It Is Not Over The Sea That You Shall Ask Who Shall Fetch It

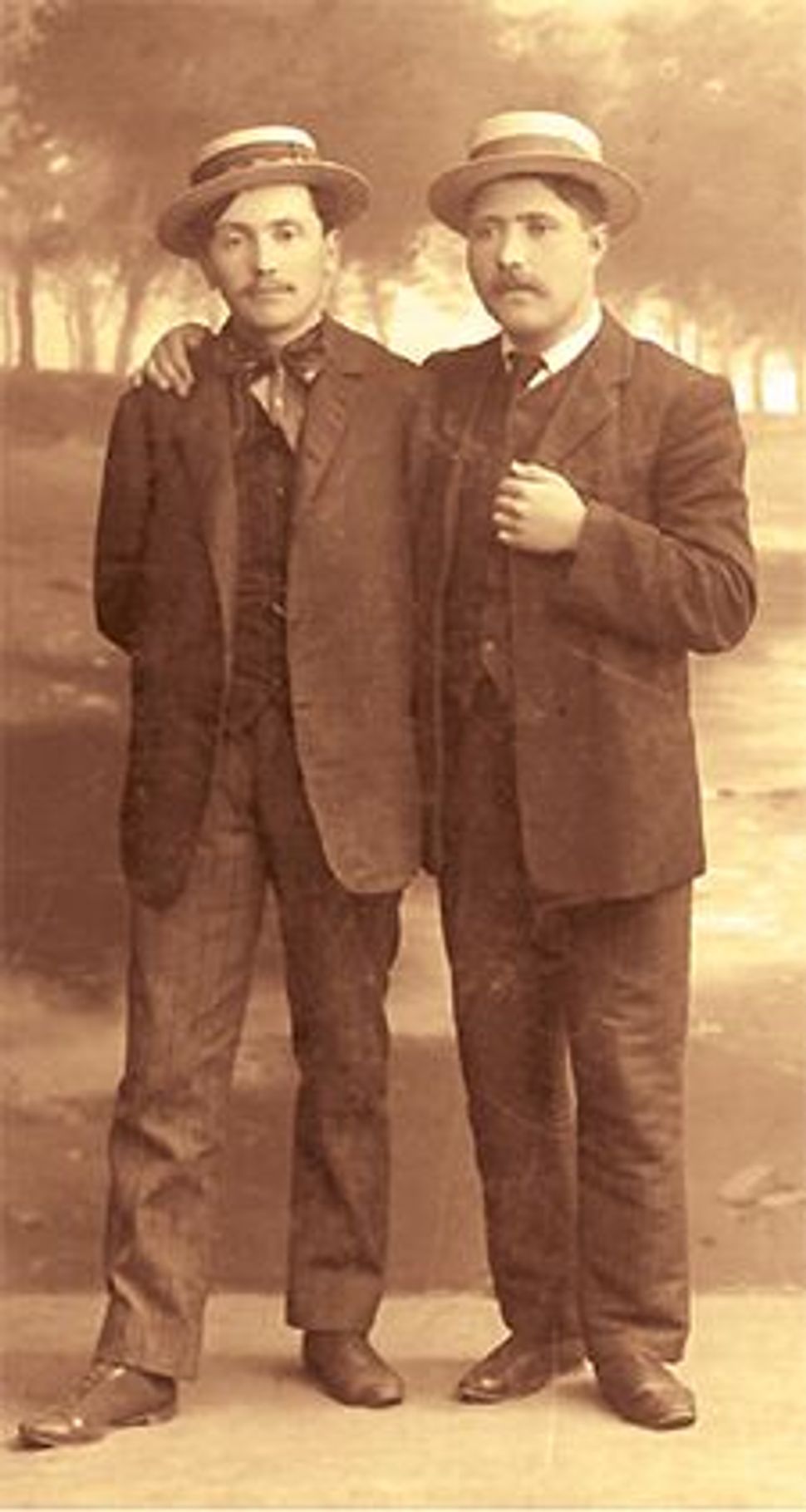

Lvov, 1908: Yosef Chaim Brenner and Gershon Shofman looking svelte in boaters. Image by COURTESY OF THE PINHAS LAVON INSTITUTE FOR LABOR MOVEMENT RESEARCH

Literary Passports: The Making Of Modernist Hebrew Fiction In Europe

By Shachar M. Pinsker,

Stanford University Press, 504 Pages, $60

American Hebrew Literature: Writing Jewish National Identity In The United States

By Michael Weingrad

Syracuse University Press, 280 pages, $34.95

Lvov, 1908: Yosef Chaim Brenner and Gershon Shofman looking svelte in boaters. Image by COURTESY OF THE PINHAS LAVON INSTITUTE FOR LABOR MOVEMENT RESEARCH

Since the 1783 founding of the journal HaMeasef in East Prussia, the Diaspora has been home to modern Hebrew literary production. In fact, during the course of the 19th century, Hebrew literary production spread throughout Europe and arrived in America. By the early 20th century, as a Hebrew literary center emerged in pre-state Palestine, Hebrew literature was already in full flower in Europe and the United States.

But the 1948 establishment of the State of Israel captured the world’s imagination and led people to view modern Hebrew literature as synonymous with Israeli literature. While this blurring initially brought curious readers to Hebrew literature, later, after the Lebanon war of 1982 and intifadas, Israel’s more troubled international image meant that the identification of Hebrew with the state was deterring potential American readers. By shifting attention back to the production of modern Hebrew literature on European and American soil, authors Shachar Pinsker and Michael Weingrad call attention to the rich diversity of the Hebrew literary corpus and new, reinvigorating directions for its study that leave it poised to capture a broader audience. Pinsker focuses on Hebrew fiction created in Europe, while Weingrad looks at writing in the United States.

Interested in the transnational study of European modernism, Pinsker gravitated to the study of European Hebrew literature produced between 1900 and 1930. He demonstrates how a loosely linked group of restlessly mobile Hebrew writers lacking national affiliation or state or territory to call their own produced a vibrant modernist literature.

Confronted by urban life in diverse European capitals, these authors seized on the tension between contemporary currents of European cultural life and the religious traditions, texts and norms of their East European childhoods. As the literary café replaced the synagogue, heder, and house of study as the primary location of culture, the billowing smoke and empty coffee cups helped Hebrew writers give shape and passion to this tension. Feelings of marginality similar to those felt by other modernist writers further contributed to the creation of a complex psychological literature portraying their characters’ struggles with issues of sexuality and gender.

While dubious that they could overcome their fragmentary sense of existence, these Hebrew writers, like their non-Jewish modernist counterparts, nonetheless continued to yearn for the sublime. Pinsker points out how their desire for unadulterated religious experience finds voice in their purportedly secular writing. While the works of Hebrew writers like Uri Nisan Gnessin, Yosef Hayyim Brenner, Gershon Shofman and David Fogel rarely find treatment alongside works by Oscar Wilde, Arthur Schnitzler, Andrei Bely or Marcel Proust, Pinsker indicates how they can play a fruitful role in discussions of European modernism’s relationship to urban and religious experience, as well as sexuality and gender.

An expert in American Jewish culture, Weingrad could easily have written a parallel study about Diasporic Jewish modernism drawing on Jacob Glatstein and. A. Leyeles’ Yiddish poetry or Louis Zukofsky and Charles Reznikoff’s English verse. But Weingrad’s decision to investigate American Hebrew literature, which had its heyday between 1915 and 1925, addresses American Jewish culture and its relationship to the national and literary traditions of its host society. While American Hebrew writers had the ability to produce modernist literature — as Weingrad shows through analysis of prose and poetry by Shimon Halkin and Gabriel Preil — they largely eschewed innovation for innovation’s sake, which they saw infecting European and Palestinian Hebrew literature. Weingrad works to get at the heart of the issues that led them to leave their work open to criticism as stylistically conservative and uninnovative.

In contradistinction to Stephen Katz, one of American Hebrew literature’s leading scholars, who views this literature as part and parcel of the Americanization process, Weingrad sees it as a literature produced by a loosely linked group who nonetheless joined together to assert a Diasporic Jewish national identity intended to cultivate and preserve a 3,000-year-old Hebraic tradition against external threats. Rather than passively accede to Americanization or an urban sense of social and psychic fragmentation, Weingrad tells us, American Hebrew writers worked to forge bonds with other Hebrew culturalists in the U.S. who were equally committed to Jewish continuity through creation and consumption of a literature portraying their shared struggles to balance elements of Western modernity and Jewish tradition.

Although similar to the group studied by Pinsker in its commitment to Jewish continuity, American Hebrew writers were alive to American landscapes and freedoms. Yet, as Weingrad shows, they proved unwilling to embrace America as a Promised Land as their Puritan predecessors had, questioning America’s ability to offer meaningful cultural autonomy. For them, America constituted a simultaneously seductive and sinister refuge.

America’s seemingly paradoxical nature found voice in a variety of different ways. Poems about Native Americans constitute one example. Poems like pioneering American Hebraist Benjamin Silkiner’s “Before the Tent of Timmura” express their poets’ sense of at-homeness in America by demonstrating familiarity with native peoples and their literary representation in American works like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Hiawatha.”

Yet, as Weingrad shows, the Native American characters in these poems simultaneously serve as personae through which Silkiner and other Jewish writers voiced their anxiety about the decline of Hebrew culture and Judaism in America. And American Hebrew writers faced a double bind in their interactions with rural America. Works which portray Jewish journeys to small-town America, such as the short story “Amos the Orange-Seller” by Bernard Isaacs, show the difficulties of Jews attempting to assimilate. While knowledge of the Bible gains Amos access to small-town Protestant society, it simultaneously dooms him to live on its margins. As a descendant of Hebrew prophets, he proves fundamentally unassimilable to Christian society.

By highlighting modern Hebrew literature’s ability to contribute to the quality and the study of European literary modernism as well as to American Jewish literature and the study of its relationship to American culture, Pinsker and Weingrad breathe new life into American Hebrew literary studies, suggesting how modern Hebrew literature both could and should reach a wider audience.

Philip Hollander teaches Israeli literature and culture at University of Wisconsin – Madison.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO