For Henry’s Sake: Pioneering a Genetic Frontier

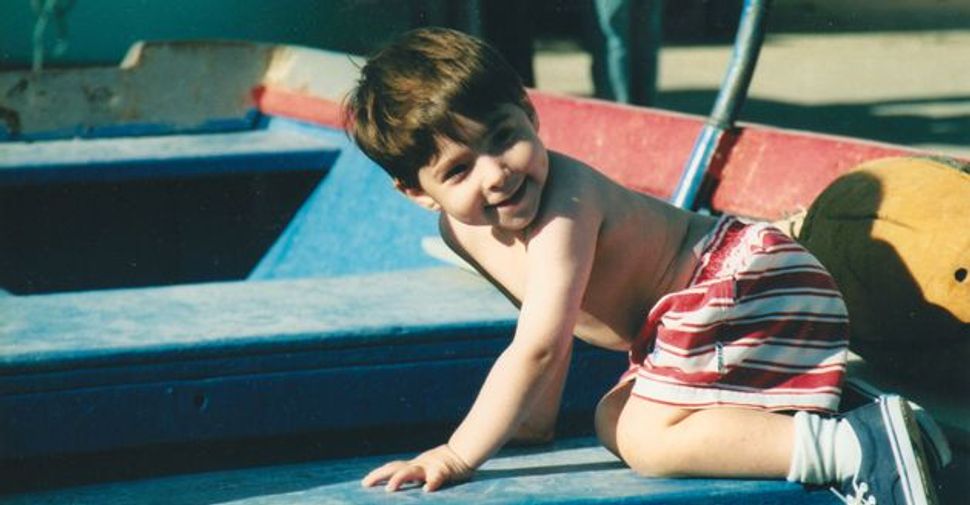

At Play: Henry Strongin Goldberg, pictured here on a family vacation in Spain at age 2, was born with Fanconi anemia, a fatal genetic disease. Image by COURTESY OF LAURIE STRONGIN

Ten years ago, the first-ever bone-marrow transplant was performed using the umbilical cord blood of a baby deliberately selected and implanted through a combination of in-vitro fertilization and genetic testing to save the life of his older sibling.

The embryo-screening procedure known as pre-implantation genetic diagnosis, or PGD, had previously been used to enable parents who were carriers of deadly childhood diseases like Tay-Sachs to knowingly get pregnant with healthy babies. But the birth of Adam Nash in August 2000 marked the first time that the procedure was used to produce a disease-free baby who would also be a perfect bone-marrow donor. Adam saved his sister Molly’s life through the risk- and pain-free donation of stem cells from his umbilical cord, which would otherwise have been discarded as medical waste.

Reaction to the news of the first so-called “savior sibling” was swift and wide-ranging. Doctors, bioethicists and religious leaders, as well as families facing the premature death of their young children, voiced opinions ranging from enthusiastic support for this life-saving medical breakthrough, to concern over the potential for its abuse, to calls for it to be banned. Mine was among the voices of support. But it wasn’t the first time I had advocated for PGD.

My son Henry was born with a rare, inherited Jewish genetic disease, Fanconi anemia, which neither my husband, Allen Goldberg, nor I had ever heard of before. Among the first things we learned about FA was that it had the impossible-to-accept label “fatal.” The only hope for Henry was a bone-marrow transplant, which he was expected to need before he reached kindergarten. In 1995, when Henry was born and diagnosed with FA, transplant survival rates were dismal. In fact, no one with Henry’s type of FA — the type that occurs in the Ashkenazi Jewish community — had ever survived a transplant without a perfectly matched sibling donor.

Henry’s diagnosis was a shock. Like many Ashkenazi Jews, Allen and I underwent genetic testing prior to getting married to determine whether or not we were carriers of Tay-Sachs. We both tested negative. Since neither of us had any history of genetic disease in our families, we were unconcerned about passing along anything deadly to our children.

But that is exactly what we had done. We had unknowingly given FA to Henry at the same time we gave him brown hair, brown eyes and the absolute cutest dimples I had ever seen. Because Allen and I were both carriers, we had a 25% chance with each pregnancy that we would pass along the same death sentence. We wanted to have several children, but Fanconi anemia made family planning about a whole lot more than love and sex. All of a sudden, it was a complex puzzle of genes, statistical probability, prenatal testing and life-or-death decisions. It wasn’t just about creating life, but about avoiding certain death.

We refused to accept Henry’s fate without a fight. From the moment of diagnosis, we searched tirelessly for someone in the medical world who would help us save Henry. In the spring of 1996, our efforts paid off. We learned of a brand-new, untested medical procedure that could guarantee at the moment of pregnancy that our baby would be free of FA and also be a perfect genetic match to Henry and therefore his life-saver.

At that time, I was in my first trimester of pregnancy, with eight weeks to go before a prenatal test could tell us whether or not the child I was carrying had FA. PGD was the lifeline out of this horror. Next time, PGD would replace luck — which was what I was counting on for my current pregnancy — with certainty.

We got lucky. Our second son, Jack, now 13, was born healthy, which felt like a miracle despite the battery of tests that told us it would be so. Immediately following Jack’s birth in December 1996, we set out to conceive again, but this time using PGD in the hope that we could have another healthy baby who would also be Henry’s savior.

Allen and I entered completely uncharted territory. As the first people in the world to use this technology for this purpose, there was no precedent, there were no books or articles to read and no support groups. There were no established ethical guidelines or government or industry regulation of PGD. There were no guarantees except that the unknown held possibilities that otherwise eluded us. We were comforted by the consistency between our pursuit of PGD and the core Jewish value of pikuach nefesh, that every effort must be made to save a life.

We attempted PGD nine times over a period of three years, during which time we were caught in the crossfire of the national stem-cell debate and suffered from politically motivated delays that may have cost Henry his life. A mix of technological challenges typical of life on the medical frontier, statistical improbability (each embryo had merely an 18% chance of being both FA-free and a perfect match to Henry) and bad luck doomed us to failure. By the spring of 2000, we ran out of time. Henry’s health was deteriorating, and he needed an immediate transplant. Henry’s transplant occurred at the same time and same hospital as Molly Nash’s. Henry’s was from an unrelated donor, Molly’s from her perfectly matched brother Adam. Molly’s went smoothly, as expected. Henry’s was rife with complications. Ultimately, his body rejected it. In December 2002, Henry died at the age of 7.

So much has changed in the decade since we first tried to conceive using PGD. Carrier screening has expanded well beyond Tay-Sachs to include Fanconi anemia, Gaucher, Canavan and more than a dozen other diseases that disproportionately affect people of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage. Meanwhile, fears that PGD would lead to a widespread era of sex selection, or that the children conceived in part to help a sibling would feel unloved or exploited, or that PGD would offer a slippery slope to a world of eugenics have proven unfounded. In fact, the technology has improved, and it has already saved hundreds of lives.

I regularly get letters and e-mails from parents with children suffering from Fanconi anemia, Diamond Blackfan anemia and other life-threatening illnesses who conceived babies who saved their siblings’ lives. The purpose of the correspondence is always the same, to thank us, and especially Henry, for being pioneers.

Widespread access to carrier testing now enables couples to make informed family-planning decisions, and PGD can help ensure that parents do not produce babies born to die. Knowing firsthand about the many beneficiaries of these astonishing advances in medicine that have occurred over a relatively short period of time, I can only imagine what the future holds.

Laurie Strongin is the author of “Saving Henry: A Mother’s Journey” (Hyperion). She is executive director of the Hope for Henry Foundation, which improves the lives of seriously ill children by providing carefully chosen gifts and specially designed programs to entertain and promote comfort, care and recovery. She lives in Washington with her husband and two sons.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO