A Manifesto for the Seventh Day

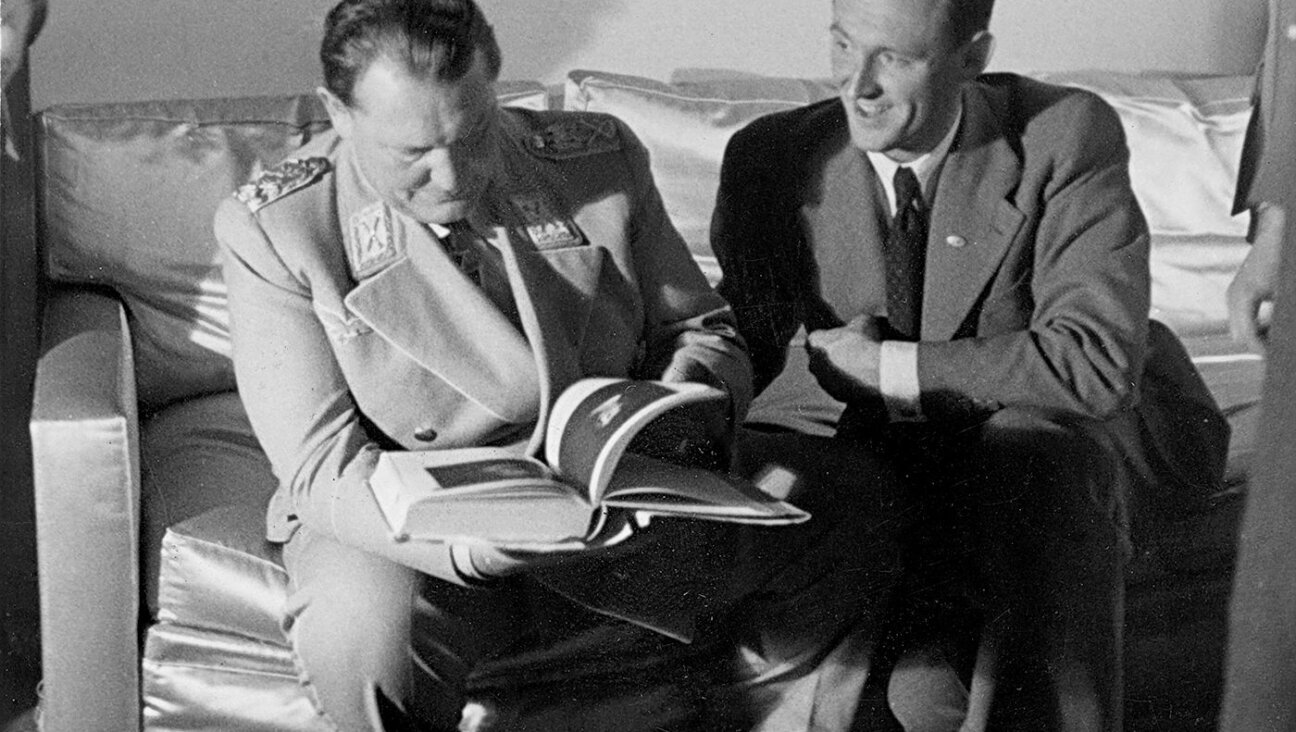

In Their Sabbath Best, With Hats and Feathers: Members of the Mount Zion Sisterhood, St. Paul, Minn., kindle the Sabbath candles. Image by JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETy OF THE UppER MIDWEST

The millennial institution of the Sabbath is currently experiencing something of a renaissance — or, at the very least, it’s the object of heightened attention — and not just within traditional Jewish circles. Judith Shulevitz’s recent book, “The Sabbath World” (Random House), a richly textured interrogation of its meaning and history, has made the rounds of the right media outlets, all of which have loudly sung its praises, while Reboot, an organization that seeks to attract the young and the hip to things Jewish, recently launched a National Day of Unplugging. Eager to “carve a weekly timeout into our lives,” Reboot also devised a Sabbath Manifesto, whose 10 principles (move over, Ten Commandments!) offer pithy, Tweet-able reasons for tuning out the world and tuning into the Sabbath. “Avoid technology,” the first principle suggests. “Light candles,” the sixth recommends. “Eat bread,” the eighth advocates, while the final principle encourages us modern-day folks to “give back.”

In Their Sabbath Best, With Hats and Feathers: Members of the Mount Zion Sisterhood, St. Paul, Minn., kindle the Sabbath candles. Image by JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETy OF THE UppER MIDWEST

The Sabbath Manifesto is resolutely up to date in every respect, from the language in which it is couched to the social concerns that inspire it. No one would mistake this document and its corresponding campaign for anything other than a digital-age phenomenon. And yet, it put me strongly in mind of an earlier effort, dating to the 1950s, that sought, with an equal show of vigor and relevance, to inspire postwar American Jews to put the Sabbath back into their lives.

Back then, technology threatened, as it still does now, to undermine the hold of the Sabbath on Jewish life — technology in the form of the automobile and the television set, that is. Forsaking the sanctuary and the dinner table for the car, growing numbers of American Jewish families took to the open road each Saturday, in search of new kinds of domestic pursuits. Alternatively, they stayed home, especially on Friday nights, to watch television, prompting one unnamed, if rather disgruntled, communal official to note that “paradoxical and outrageous as it may seem, Friday night services in this day and age have been placed in sharpest competition with a variety of opportunities in the fields of entertainment. Television is only a latest newcomer to the series of distractions.”

Determined to lure away contemporary American Jews from their TV sets and their cars, respectively, and reintroduce them to the pleasures of the Sabbath, lest it fall into desuetude, Conservative Jewish leaders of the 1950s devised the “National Sabbath Observance Effort,” which they pitched largely through the good graces of the synagogue sisterhood. In lieu of running errands and shopping and doing all those things that transformed the Sabbath into Saturday, American Jews across the country were actively encouraged to light candles; partake in a Sabbath meal, preferably one with gefilte fish and challah, and attend services.

Before long, it became clear that postwar American Jews had difficulty fulfilling even these modest goals, prompting sisterhood leaders and their rabbis to come up with all manner of supplemental initiatives to supply the “know-how and the know-why” of traditional Sabbath observance. In Norwich, Conn., the local Conservative synagogue sponsored a “Sabbath Institute” at which congregants were instructed in the preparation of a “typical Sabbath lunch.” Meanwhile, at a similar Sabbath institute in Miami, participants received a seven-page leaflet, “Making Our Home Shabbosdik,” to acquaint them with the “four basic steps” of Sabbath observance.

Despite the best of intentions, this campaign and others that followed in quick succession ultimately petered out, much like the sputtering of Sabbath candles. The preparation and consumption of gefilte fish and challah, and the singing of z’miros, songs in celebration of the Sabbath, were all well and good, but they were simply no match for the blandishments of modernity.

Daunted but unbowed, America’s rabbis tried again. Those within the Conservative movement sanctioned driving to synagogue on the Sabbath, hoping that would get their congregants into the pews of the sanctuary. It didn’t. Others took to speaking lyrically of the health benefits that would result were American Jews to rest on the seventh day of the week. Keeping the Sabbath allegedly restored one’s equilibrium and brought “release” from the cares of the workaday world, alleviating the “mental uneasiness and ennui which are so often characteristic of modern man,” or so it was said. That claim didn’t go too far, either.

It’s too early to tell whether today’s call for the reinvigoration of the Sabbath will enjoy greater success than those of its predecessors. But one thing is certain: It’s not for want of trying, as each generation creates a Sabbath in its own image.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO