Honor and Comfort

David Zinner is executive director of Kavod v’Nichum (Hebrew for “honor and comfort”), an organization that provides assistance in forming new burial societies, trains prospective burial society members, and identifies resources about Jewish bereavement practices for hevra kadisha groups and bereavement committees in synagogues and communities throughout the U.S. and Canada.

Zinner is a co-founder of the Gamliel Institute, which educates and trains a corps of future leaders who have a strong interest in creating a holistic “continuum of care” for the end of life in their local communities. The program is a unique blend of Jewish communal obligation; care for the poor and elderly; consumer protection, Jewish continuity and spiritual inspiration. The Institute will offer both a certificate program and individual courses that cover life’s spectrum of illness and comfort, death, funerals, burial and mourning.

Noach Dzmura: What is the mission of Kavod v Nichum?

David Zinner: We’re very oriented toward conferences, and providing education and training opportunities in addition to tahara (“ritual purification”) training. We’re interested in building communal leadership and empowering people.

What drives the hevra kadisha movement in liberal Jewish circles?

Many things! People working out their own issues, people who want to reconnect with Judaism or with spirituality and this is their entry for it, people who feel they owe it to their parents or grandparents because it’s a family tradition or because they were helped by the hevra in their own community, people who feel a communal responsibility outside of all that, people who like to do stuff with their hands as opposed to just with their brain, people who are into organizing and see this as a way to motivate people and build connections. And more.

Do you track how this movement grows?

No. It’s too hard to keep track of. If someone asked me how many hevras are there, I couldn’t answer. Not only do I not know, but I wouldn’t even be able to tell, because some hevra can serve four different groups. One hevra can morph into another hevra just by the addition of two or three people and a change of location. One person can belong to five hevras. It’s really difficult. Now, we can tell when a new hevra is starting. But it’s hard to get an overall count.

Is there a way to show that traditional burial is becoming more common?

I can’t point to a statistic. I can point to anecdotal things. I helped a group get started in Pittsburgh; I helped a group get started in Chicago. I talked to a group in New Jersey, and five years later they called me back and said it didn’t work, please come back and try again. [Laughs] I consider that a success, that they are willing to try again. I talked to a group in the Boston area, and they said they couldn’t do it; it didn’t work.

What causes a hevra to succeed?

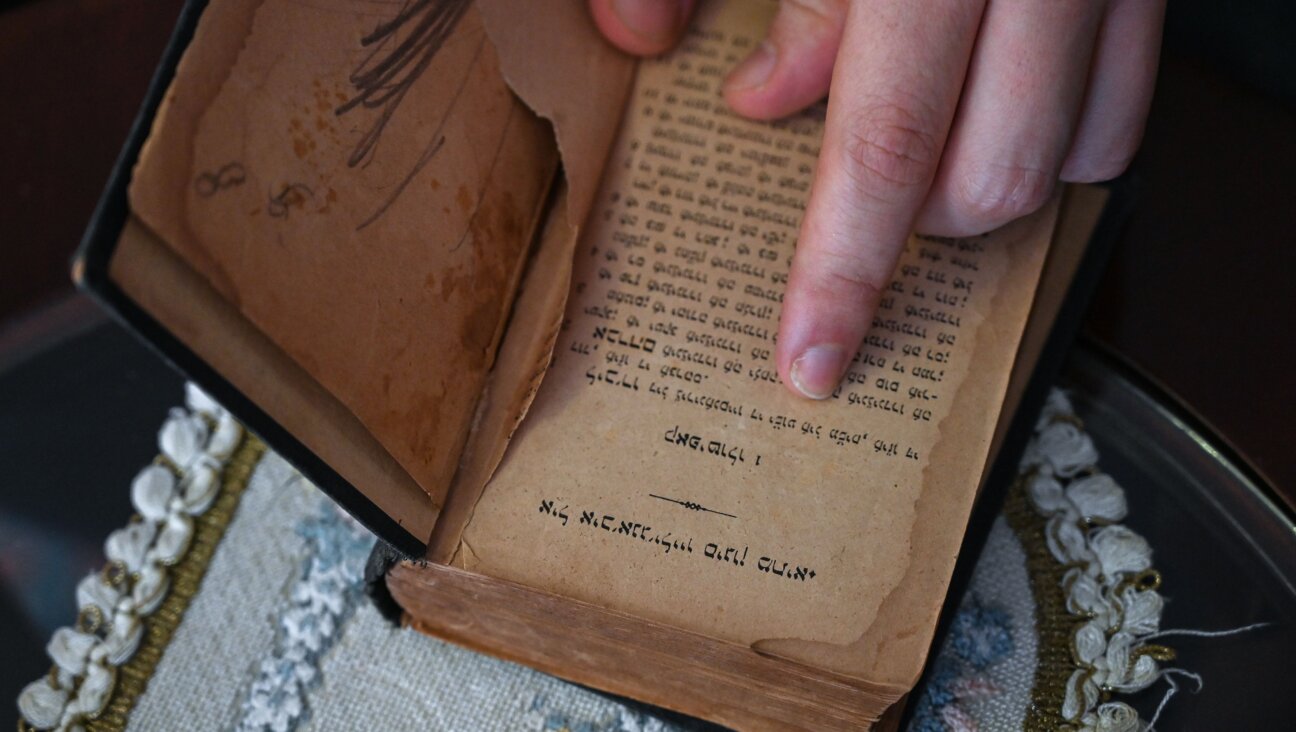

Sometimes there are different things that will cause the right mix of people and events to help the group form. Some groups form after a traumatic experience — say, for example, a beloved member of the congregation dies, or a young child’s death gets them to finally come together. Other groups they just talk and discuss and read before they get around to doing tahara. They read all the tahara manuals, study what the prayers mean, read Maurice Lamm’s book (“The Jewish Way in Death and Mourning”). Then it’s been a couple of years, and while the group feels they know a lot, they don’t feel fully trained. This is one of those rituals that is passed down in some ways. Each generation trains the next; each group trains new participants. If that kind of passing down hasn’t happened, people can become obsessed with “doing it exactly right.” [For instance,] if you tie the knot [on the shroud] incorrectly, it’s gonna be a bad thing and who knows what’s going to happen. For some groups, precise adherence to custom is extremely important. For others, that’s not the most important thing.

I understand there are hevrot kadisha attached to synagogues, and some that are organized by a community without affiliating with a particular congregation. Are there other models?

That’s the biggest breakdown. There are also multi-congregational, where two or three congregations cooperate to form a hevra, but that becomes a lot like the community-based hevra. There’s also the funeral-home based hevra, which is a little dicey for me, because too often in the past they haven’t had the same kind of respect, they haven’t ensured the right number of people were available, they’ve mixed men and women, there’s no rabbinic supervision, so, I feel uncomfortable giving them legitimacy. Not that it’s up to me. [Laughs.]

I am curious about your ideas of rabbinic supervision. In my understanding, we are a nation of priests. There is a lot of encouragement, at least in Berkeley Calif., to do it yourself.

Well, let’s admit that everywhere in this country, and other countries too, the hevra kadisha is outside of rabbinic supervision for much of its work. In other words, the rabbi doesn’t go into the tahara room, usually, and say: “Oh no, that’s wrong! You didn’t do that right!” First of all, most rabbis don’t know, because they’re not part of the tahara team, and second, they don’t have time because they’re busy writing the eulogy at the same time. It’s traditional that hevras are on their own. In olden days, they were a force unto themselves. But today hevras really need rabbinic supervision — maybe supervision is the wrong word — hevras need rabbinic cooperation, because they have questions that come up. But they also need to educate the rabbis about what they do, before the rabbis go about making decisions. Or else the rabbi can say something, and the hevra can say, “That makes no sense.” For example, one time a rabbi spoke at a meeting of all his hevras, and said, “I want you to do the following with tubes and needles: Take this tube out, and stitch it up this way.” And the hevra members are looking at each other and saying: “What? We’re not medical people. We don’t know how to do stitching. We’re not going to be stitching on a dead body!” The rabbis need to understand what goes on so that they can be working with these groups when they give advice. At the same time the hevra needs the rabbi to stand up there [on the bimah] and say, “We really need people to come out and join the hevra kadisha — it’s really important work!” It’s a two-way street. They both need each other.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO