Not Science Fiction

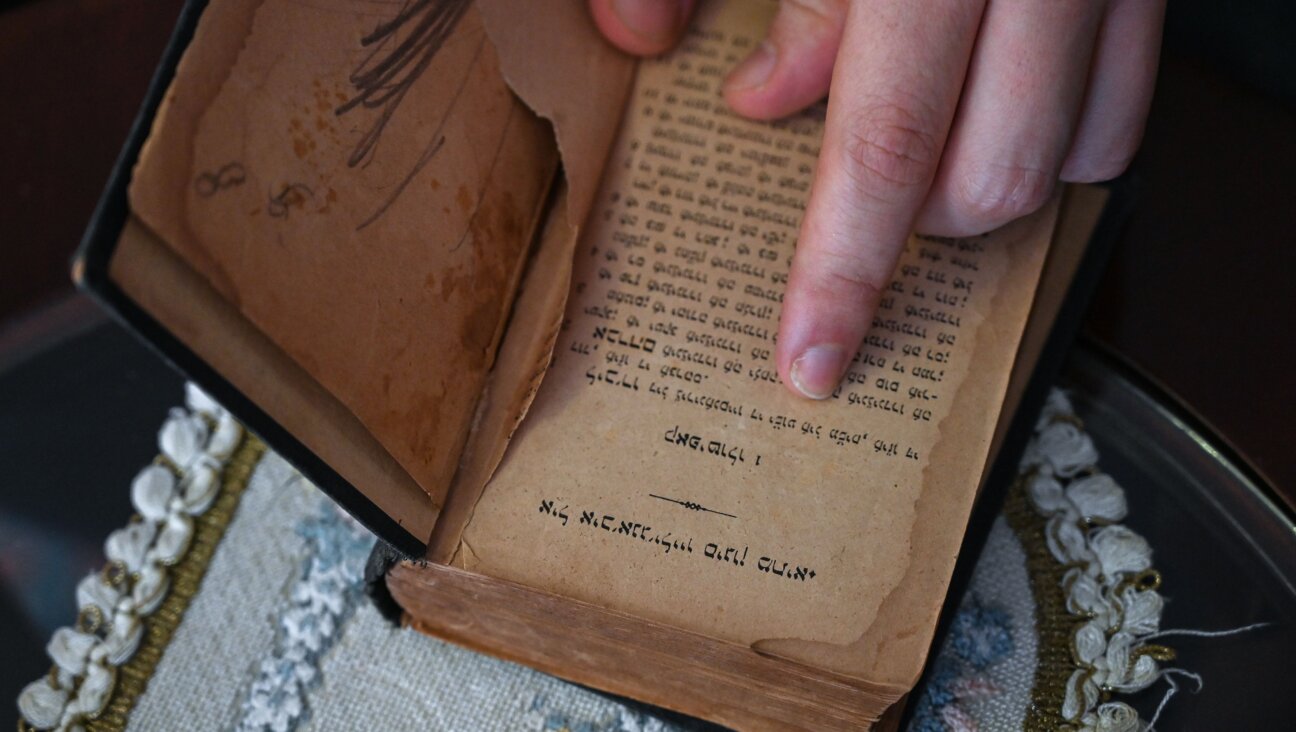

Eccentric Devotion: Author, Jonathan Lethem, says Phillip K. Dick will be read alongside literary greats, and not just by lovers of Science Fiction. Image by Tom Erikson

Imagine worshipping a writer in early life, then becoming an essential force in preserving his work. This is Jonathan Lethem’s labor of love, to keep us reading Philip K. Dick. A music aficionado and MacArthur Genius Grant recipient, Lethem now has his own vast canon — seven novels, numerous stories, a novella, a comic book and more. His personal success makes this posthumous relationship unique. In choosing four of Dick’s later novels — “A Maze of Death,” “Valis,” “The Divine Invasion” and “The Transmigration of Timothy Archer” — to edit and contextualize, Lethem hoped to revise the common thinking that Dick’s science psychedelia and religion writings were separate trajectories entirely; rather, he proposes that they came from the same fruitful place.

The newly released volume is the third collection of Dick’s books published by The Library of America. Lethem spoke recently with the Forward’s Allison Gaudet Yarrow about how he came to work with Dick’s oeuvre; about his own forthcoming novel, “Chronic City” — out in October — and about writing his most overtly Jewish work yet.

Allison Gaudet Yarrow: How did the project come about?

Jonathan Lethem: I was getting ready to drop out of college. I wanted to write novels instead, so I conceived the idea that I should run away to California and deliver myself to Philip K. Dick and be his acolyte. He died. I went anyway. By dumb luck I introduced myself to [a journalist and critic] who was running his estate. He ran it as a club. I was a junior member. Dick’s work was rather miraculously revived into public life…. It’s very rare for anyone in literary history to come back from being totally out of print to being in the canon. And that’s what happened.

Eccentric Devotion: Author, Jonathan Lethem, says Phillip K. Dick will be read alongside literary greats, and not just by lovers of Science Fiction. Image by Tom Erikson

How did that happen?

A very dedicated fan base, the eccentric degree of devotion you see in something like “Star Trek.” [Dick’s] material was so prescient about late 20th-century culture that it took a while for people to realize he had named everything we were going through.

The novels in this collection seem to have been penned, for the most part, in incredibly short bouts of genius — two weeks for “Valis,” and “The Divine Invasion” in less than a month.

That method remains very true throughout all his decades. He didn’t ever stop to catch his breath; he just wrote…. For my money, “Valis” is one of his top-drawer masterpieces. I can’t think of a novel in the English language that is a comparison for it.

What was it like to work with his prose in such a close way after loving his work?

The novel that I’ve got coming out in October [“Chronic City”] is in some ways back to his territory, but in a very different way, in a way I never could’ve conceived when I was 21 years old and trying to be the next Philip K. Dick.

How has his writing influenced your own?

His sense of humor, his perverse commitment to his own ideas of what’s funny or interesting, his sense of velocity and strangeness. When I was growing up, I couldn’t imagine a writer who satisfied more of my appetites as a reader, and so I thought, I’ve got to try to do this.

Why aren’t there more literary writers and readers of science fiction today?

I don’t think the divisions are as simple as the bookstore shelves would suggest.… This kind of writing has become incredibly central to our literature, and it isn’t very interesting to worry about what the context of its original publication was. The question is, how good is it? How lasting is it? Dick’s novels will be read for centuries side by side with something like “Ratner’s Star” by Don DeLillo or “Gravity’s Rainbow” by Thomas Pynchon, and people aren’t going to even remember that one of those three writers was segregated into a publication ghetto.

You’ve written about art borrowing from other art. In our culture, why are we afraid of admitting it?

There’s an economic motive for propping up or exaggerating the romantic ideal of artists as originators and their results as pure and free, but very few things are brought into being in a debt-free manner. Everything is learned through borrowing, imitation, repurposing and remixing. Things don’t pop into existence in a vacuum.

You’ve also written a lot about New York identities. What is your perspective on Jewish identity in New York, and how has that changed?

I grew up in the most typical New York Jewish identity, which was very unselfconsciously secularized, and taking itself for granted. I had one Jewish parent, not two. I did a Jewish holiday here or there, but it was part of a cultural menu. I didn’t feel very Jewish or even think about it much until I went elsewhere. I went to California and was there for 10 years. There are plenty of Jews in California, but there’s nowhere like New York. There’s just nowhere where it’s so taken for granted, so knit into the urban identity. You know, Bernard Malamud has that quote that all men are Jews — I don’t know if its true, but all New Yorkers are Jews for sure.

Do you think that’s still the case?

I can certainly imagine a thousand ways someone would resist that remark, but the life of the city seems to me to be created by tendencies towards intellectually restless, mercantile, suspicious and ironic people in some fundamental way. In New York, everyone’s Jewish.

You often write about the outsider experience, which seems so intrinsic to the Jewish sensibility.

The way I observed Jewish identity was through a stronghold. I write about outsiders banded together. That’s very important to me. I’m actually gearing up to tackle some Jewish identity stuff in this next novel I’m going to write. It’s set in Queens, and I suppose it might be my most sincere attempt at accepting what has always been an ambivalent part of my assignment, something I’ve only played footsy with in a book like “Fortress of Solitude”: The characters are Jews, but don’t care that they’re Jews. Or they barely mention it. I think I’m going to go a little more head-on in that material for myself.… They’ll be really beJews. Or at least admit that they’re trying not to be Jews. Whatever they need to do. It’s going to be set in the ’50s and ’60s, so more my grandmother and mother’s world, less my own. Just by moving backwards in time, I’ll be touching that element.

Where are you in your process with that novel?

Barely beginning. Accumulating materials. Actually having interviews with family members to pull some evocative narrative threads out of our family lore.

What is your writing process like? Is there a lot of interviewing and gathering at the outset?

Some of what I do springs so totally from my imagination; other things are grounded in material that I do have to explore. The bigger the book, the longer the warming-up process. It’s just like feeling around the edges of a mountain before you climb it.

“Chronic City” brings your fiction back to New York in a sense. Is it good to be back? What makes this story unique?

Yes, it’s certainly a return to New York, though not to Brooklyn. Though I suppose it is a Brooklynite’s view of Manhattan: a fantasy, a scandal, a conspiracy, rather than a real place. Of course I’m in no position to judge it myself yet; it’s too fresh, and I’ll need to wait to see what others think before I can resolve my own feelings about it (if I ever can). But my first impression of it is, frankly, amazement: I think it’s the most mysterious book I’ve written.

You wrote an introduction to Nathanael West’s second novel, “Miss Lonelyhearts,” which is about the trappings of being an advice columnist. The Forward has been running the Bintel Brief advice column since 1906. Have you or would you ever consider moonlighting in this field?

I’ve never been tempted, though I do find myself reading them from time to time. But like Miss Lonelyhearts, I suppose I find the letters much more compelling than the answers, which I tend to skip!

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO