Six Days, 40 Years of Controversy

The weeks following the Six Day War found Israelis not sure if they were awake or dreaming. Everyone spoke of miracles, of the supernatural forces that had guided the Jewish army to such overwhelming victory. The names of the generals — Rabin, Hod, Sharon, Peled — resounded like the names of gods. The people once again felt chosen. The whole country seemed to pinch itself again and again, like Gulliver in the land of Lilliput, not quite sure that it had really so suddenly, scarily, exhilaratingly grown to three times its size.

In the middle of these heady days, Amos Oz, a 28-year-old writer from Kibbutz Hulda who had just published his first novel, was assigned a seemingly impossible task: The leaders of the kibbutz movement asked him to begin constructing a narrative of the war, one that might cut through the national dreaminess. Oz and another young kibbutznik-writer, Avraham Shapira, set out to interview the warriors. The resulting book, “Soldiers Talk,” was a heavily edited compilation of 30 group conversations they conducted with 140 soldiers.

Within weeks it became a best-seller. Israelis fell in love with the image it presented of their young fighters. In the words of Tom Segev, whose recent history of the Six Day War, “1967,” has just been translated into English, the interviewees emerged as “gentle, peace-loving, awkward, thoughtful, sad, sensitive to human rights, and tormented by questions about the necessity of the war and the cost of victory.” This was different from the blatantly propagandistic accounts of the war that were proliferating in its immediate wake. The Israelis of “Soldiers Talk” acted in self-defense, carrying a great moral burden on their shoulders. They were heroic, but only out of necessity. They were not warmongers, but a people who fought with sadness, eager to defend their homes but not to kill or maim. “We have been blessed to have sons such as these,” Golda Meir exclaimed after reading the interviews. As far she was concerned, this was “a holy book.”

In 1971, the collection was published in English as “The Seventh Day: Soldiers Talk About the Six Day War,” and it set the tone for much of what would be written about the war for at least the next two decades. It was the spirit captured in such popular histories as “The Tanks of Tammuz,” Shabtai Teveth’s 1969 pulpy classic about the tank battles in the northern Sinai that featured the brigade commander, Shmuel “Shmulik” Gorodish, or “Six Days in June,” Eric Hammel’s gushing 1992 account of the various battlefields of the war. In these versions, the focus was always on the combat, with the unstated assumption that the war was existential. The men were nothing but decent, fighting a fight that was forced upon them. It was a vision of the war freed from the dramatic irony of what would follow the battles — the decades of occupation and its resistance.

Forty years have passed since the Six Day War, and much has changed, if not completely flipped, in the perception of Israel’s real motivation and role in 1967. Over the past 15 years, a group of Israeli writers, now known as the New Historians, has so relentlessly questioned the foundations on which this sacred narrative of the war was based that it no longer even looks like the same event. Was Israel really as threatened as it claimed to be? Were the occupations of the Sinai, West Bank and Golan Heights really only defensive measures? Was Israel simply looking for an alibi to go to war and conquer more territory? And — to put a stake in the heart of the myth — who was the war’s true Goliath, and who its true David?

Two new accounts of 1967, released

to coincide with the 40th anniversary and incorporating previously classified material, take the revisionism of the New Historians to its ultimate conclusion. In both Segev’s new book and “Six Days,” a documentary film by Israeli American director Ilan Ziv, it was Israel that had total agency — and an often malicious one at that. To hear them tell it, the Arab states simply bumbled into their belligerancy, while Israel — motivated not by self-preservation, but by the strategic, religious and nationalistic benefits of a Greater Israel — provided the true push to war. The Six Day War in these new narratives is not seen as the essential triumph for the Jewish people that it was in its time, but, through a retrospective lens, as a moment of great tragedy: the beginning of the end of the Zionist dream.

The 30th anniversary of the Six Day War held even more significance for historians than the one being commemorated this week. In 1997, the Israel State Archives were opened — in keeping with the 30-year declassification rule followed by most Western countries — and researchers were finally allowed to see what conversations took place in the critical weeks before the war. The first book to take full advantage of this archival gold has been, thus far, the most comprehensive and thorough histories of the war: Michael Oren’s “Six Days of War,” published in 2002. Drawing, as well, on the scant sources from the Arab side of the war, and from interviews with all the principal actors who are still alive, Oren laid out an astonishingly judicious version of what happened, both diplomatically and militarily, in May and June 1967. And what he discovered was what New Historians like Benny Morris had already come to guess by the late 1990s, even without the benefit of the opened archives: that the war, to a large extent, was not the result of conniving calculation on either side but rather, as Morris put it in a 1999 book, “a product of error and miscalculation.”

Segev draws on much of the same archival material as Oren — the notes of critical meetings, the diaries of key participants, official reports and memorandums — but he makes a narrative choice that gives his version a vastly different tone: He tells the story from the Israeli perspective only. Segev is concerned with how the war affected Israeli society, and, significantly, he spends the first 230 pages of his book just describing the state of pre-Six Day War Israel: the internal divisions, the political and economic malaise, and a kind of psychic incompleteness that he diagnoses in the population.

When the war arrives, it seems to be almost predetermined, willed into being by the Israeli people. The numerous complex deliberations — which make the eventuality of the war not a foregone conclusion but rather a result of conflicting egos, misunderstandings and faulty intelligence — get swept away. Instead Segev tells us that it was “not Nasser’s threats” that had brought about the rush to war, but rather:

… it was the quicksand of depression that had pulled so many people down for so many months. It was the disappointment and the feeling that the Israeli dream had run its course. It was the loss of David Ben-Gurion’s leadership, the father of the nation, coupled with the lack of faith in [Prime Minister Levi] Eshkol and the general mistrust of politics. It was the recession and the unemployment; the decline in immigration and the mass emigration. It was the deprivation of the Mizrahim, as well as the fear of them – the fear that they would erode Israel’s European society and culture, that they threatened the Ashkenazi elite. It was the difficulty of communication with the younger generation. It was the boredom. It was the terrorism; the sense that there could be no peace. All these feelings welled up in the week before the war, sweeping the state away in a tide of insanity.

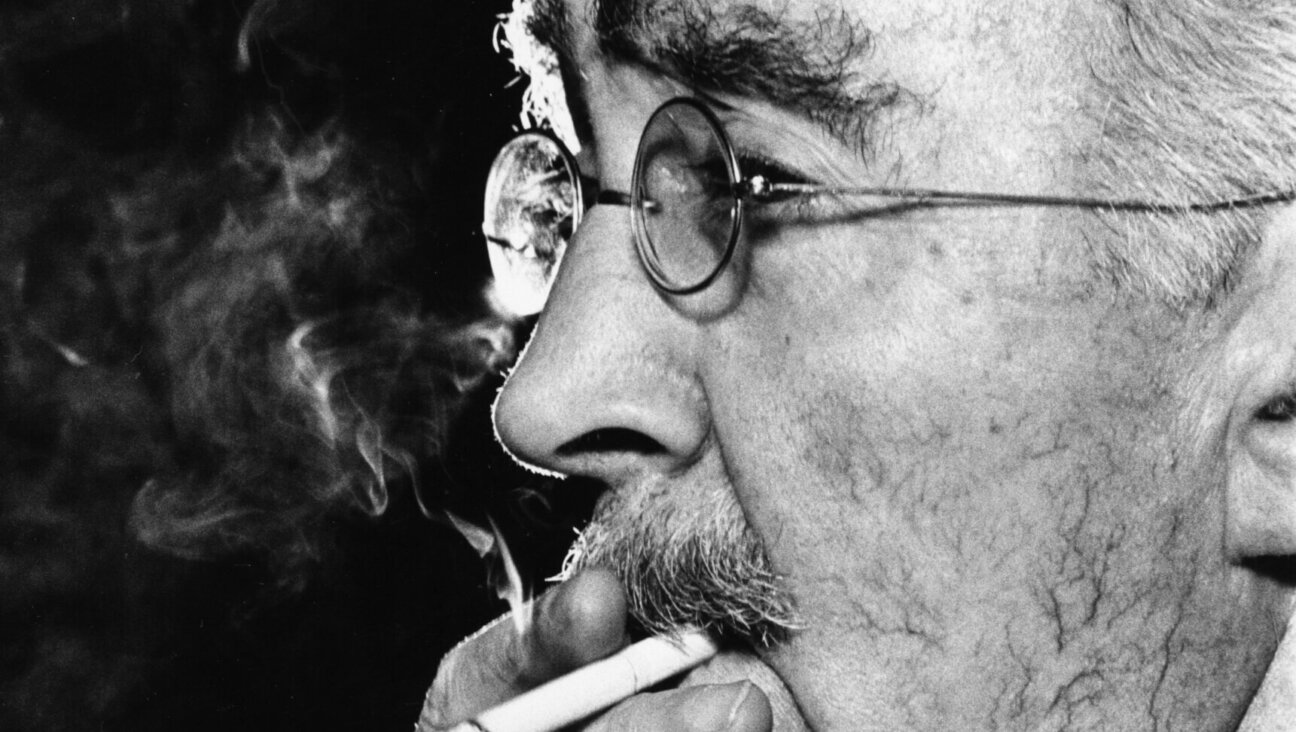

It is this “insanity” of the Israelis that becomes the guiding principle in Segev’s account. Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser’s fateful decisions — to mass 100,000 troops in the Sinai, to eject the United Nations forces that acted as a buffer between Egypt and Israel and, finally, in an ultimate casus belli, to close the Straits of Tiran — become almost footnotes. The buildup to the war, in his telling, was the story not of Arab escalation but rather of the conflict between Eshkol, the Israeli prime minister who was trying to stave off a pre-emptive attack, and the Israeli generals (led by the chief of staff, Yitzhak Rabin), pushing for a war they knew they could win even with an arm tied behind their backs. The decisive moment for Segev, the one that makes the war an inevitability, is not Nasser’s closing of the Straits, or the Americans’ refusal to back up their promises to organize a flotilla to open them up, but instead when Eshkol finally surrenders his defense portfolio to the hero of the 1956 Suez Campaign — the enigmatic and charismatic Moshe Dayan, who rides in on the shoulders of Israelis hungry for war.

Segev, in addition to writing a very readable book, can at least be commended for laying out everything he found in the archives, letting debates play out on the page as they likely did in real life. Ziv, on the other hand, draws on the archives selectively and with the goal of painting a very particular picture. His is a morality tale, not a piece of messy history. Eshkol and Nasser are given the roles of tragic heroes, while Dayan, conveniently fitted with the sinister eye-patch, is the villain.

This is a unique distortion of the record. As both Segev’s and Oren’s books show, Nasser was hardly a passive figure, and Eshkol was certainly no pacifist. Though he wanted to avoid war and was more ambivalent about the use of pre-emptive force, Eshkol was happy to make his own victory lap around the new country — upset only because Dayan and Rabin seemed to be getting more credit than he was. And if Dayan is the villain, then he was a confused and inadvertent one. Although Ziv never tells his viewers, more comprehensive histories have shown that Dayan flip-flopped about the occupation of the Golan and pointedly did not want to take all of the West Bank. Indeed, Dayan’s own memoir portrays him as a man motivated more by the need to feed his own ego than by a desire for military conquest.

The one way in which Segev and Ziv fill in the historical record is by centralizing a few episodes that have, until now, been shoved to the margins of the war’s story — mostly because they compromise the idea of a morally superior Israel. Oren, for example, devotes only half a sentence to the destruction of the Arab neighborhood in front of the Western Wall, the Mughrabi, demolished by bulldozers on the last night of the war to make room for a vast prayer plaza. About the destruction of three villages in the Latrun corridor and the expulsion of its inhabitants for no obvious reason other than to settle a historical score from 1948, Oren uses no more than a few words to describe the incident: “the Arab inhabitants, though offered compensation, were not allowed to return.” Segev, on the other hand, devotes a few pages to the destruction of the Mughrabi neighborhood, telling us about some of the 135 families whose houses were torn down, as well as providing first-hand descriptions of the expulsion from the Latrun villages. Ziv’s film even offers a full-scale re-enactment. It is in these moments when the revisionism of the two accounts seems critical for restoring to our collective memory what shame has tried to erase.

It is difficult for even the most professional of historians not to glimpse the Six Day War through the refracted lens of the long occupation to which it has led. Once the exhilaration of victory subsided and the full demographic implications of reclaiming Greater Israel became evident, the war quickly began to signify the beginning of a serious ideological divide among the Jewish people. Is it so surprising, then, that historical objectivity should become elusive? Indeed, it seems to have influenced the way that Segev and Ziv approached the vast archive, grabbing and highlighting the material that confirmed their ideas and ignoring those that didn’t.

Oren, on the other side of that ideological divide, recently wrote an article for The Jerusalem Post that accuses New Historians, Segev in particular, of using the available material to propagate “the belief — which is strongly implied, if not yet openly asserted — that Arab actions had little to do with the outbreak of hostilities in 1967, and that Israel not only failed to prevent war but actively courted it.” Oren added that, in contrast, his own examination revealed “a country and leadership deeply fearful of military confrontation, and desperate to avoid one at almost any price.”

This is perhaps an overstatement, one certainly not backed up by Oren’s own book, in which belligerent and overconfident Israeli voices do exist among those debating the pros and cons of war. Nevertheless, a narrative of the Six Day War that doesn’t include, as neither Segev’s nor Ziv’s fully does, the very real fear of existential threat that Israel experienced, the intense rhetorical and actual hostility of the Arab countries, and the varied and often confused opinions of the Israeli leadership, does not illuminate it adequately.

The origins of the Six Day War will continue to be debated, if only because the notion that it was a war both Israel and the Arab countries seemed simply to stumble into is an unsatisfying explanation for an event with such momentous historical implications. But an honest account cannot ignore that at least, in part, the war was the story of two sins colliding. Yes, the sin of mindlessness that characterized the Israeli decision to occupy land containing hundreds of thousands of Palestinians; the confusion of strength with righteousness; the self-intoxicating blindness of taking control after centuries of powerlessness. But it must also contend with the sin of the Arabs, which was more than just intolerance and intransigence. It was the classically fatal sin of hubris. Any description of that fateful war spins out from both of these, two threads that wrap the region in a death grip to this day.

Gal Beckerman, a regular contributor to the Forward, is writing a book about the Soviet Jewry movement, to be published next year by Houghton Mifflin.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO