Excerpt: Sam Apple’s ‘American Parent’

Raising Kids Today: Sam Apple?s new memoir, ?American Parent.?

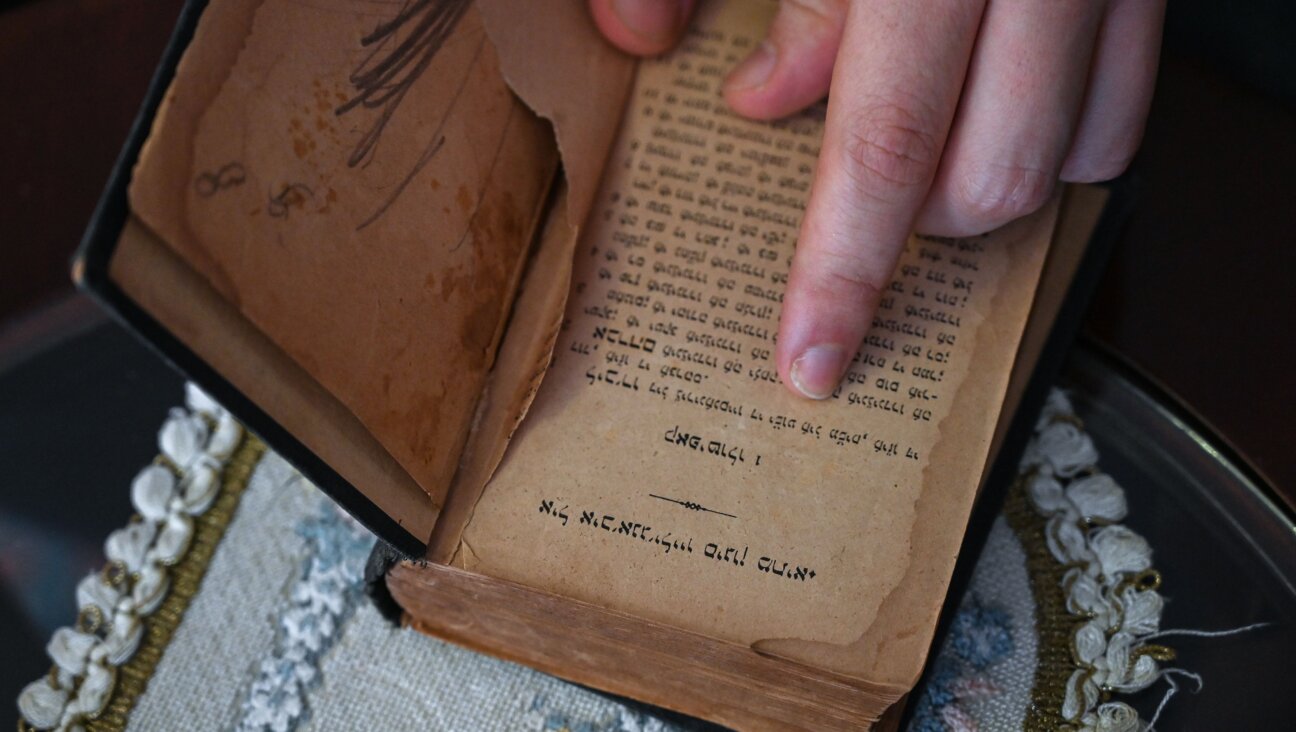

Unlike most people writing about circumcision, I wasn’t especially interested in the medical debates surrounding the procedure. It was the strangeness of the ritual that captivated me. Plenty of the Jewish rituals sometimes feel odd in the context of my otherwise modern life, but no other ritual seemed as archaic or mysterious as circumcision. I planned to learn about the origins of the ritual and about how circumcision had found its way into so many diverse religious cultures. But while I was most interested in the history, my plan was to extend the discussion to my own feelings about circumcision—my working title was “In Search of My Foreskin”—and, in the process, explore my own Jewish identity. And if I was going to write a personal book about circumcision, I thought that the scene of my own cutting might be a logical place to start.

I asked my relatives what they recalled about my circumcision, but to my frustration, the single clear recollection came from my grandmother, who remembered that my great-grandfather, Rachmiel, had led a celebratory conga line. I was amazed to learn that the removal of my foreskin had gen erated so much enthusiasm.

But I was looking for a more complete picture of my eighth day, and if my relatives couldn’t remember the event, there was still one person who might: my mohel. A mohel, or Jewish ritual circumciser, is sometimes but not always a rabbi. My mohel was an orthodontist. I learned this from my father, who said that he had been friendly with my mohel at our synagogue in Houston, where I grew up. My father recalled that my mohel had worn a cowboy hat and boots whenever he did a circumcision and that he had circumcised the sons of so many East Coast transplants that he became known as the Yankee Clipper.

Raising Kids Today: Sam Apple?s new memoir, ?American Parent.?

It took only a quick Google search to find my mohel’s phone number, but making the call wasn’t as easy. I wasn’t sure how to explain what I wanted without sounding like a lunatic. I picked up the phone, put the phone down, paced around the apartment, and picked up the phone again. Then, I dialed my mohel’s number.

My mohel said hello with a slight Texas twang, and I introduced myself as someone he had circumcised a long time ago. My mohel seemed entirely, astonishingly, unfazed by my announcement.

“Great to hear from you,” he said. It was almost as though he had been waiting for my call for the last thirty years.

“So I guess you’re wondering why I’ve called you,” I said.

“No,” my mohel said. “You can call me anytime you want.”

The response put me at ease. My mohel and I chatted about a few people we knew in common from Houston and then, even before I had begun to ask him about the scene of my circumcision, he invited me to visit him at his home in Howard, Colorado, where he was spending his retirement with his second wife. Four months later, I was standing in the passenger pickup lane of the Colorado Springs airport, where my mohel and I had arranged to meet. I didn’t know what my mohel looked like and for several minutes I peered through the windows of the idlingcars, wondering if one of the drivers might have circumcised me. Then a Ford Explorer pulled up with a handwritten sign bearing my name taped to the window. Inside the car, the Yankee Clipper waved excitedly. I opened the car door and shook his hand. He wore a gray polo shirt almost identical to my own, a black baseball cap, and a money pack around his waist. We began the two-hour drive to my mohel’s home in Howard, a small mountain town 150 miles south of Denver. My mohel did most of the talking. He was the type of guy who had acquired a lot of interesting information in his life, and he was not afraid to share it. He told me stories about his army years and about doing circumcisions in Beaumont, Texas. He had a full white mustache and boyish, darting eyes that came to life as he spoke. I noticed a cut-up cereal box on the floor of the car. “Postcards,” my mohel said, picking up on my interest. He explained that he rarely uses regular paper. Next to the postcards was a small pile of envelopes made from newspapers. Later, I learned that he mails about twenty of these homemade letters a week, not including his three or four daily sweepstakes entries.

After a few minutes, we stopped for lunch at an empty restaurant. We both ordered black bean soup and small organic salads. Between spoonfuls of soup, I inquired about my circumcision. Had there been anything unique about the event? My mohel couldn’t remember but didn’t think so. Did he remember my family’s conga line? No. Anything special about the food, perhaps?

No. “Unless there was some sort of medical problem it’s hard for me to remember much,” he said.

I wasn’t ready to give up. I had read that the foreskin is typically buried after a Jewish circumcision, and before my trip I’d wondered if my mohel might be able to recall what he had done with them after the ceremonies. Had he thrown them out? Tossed them into a Dumpster behind a Taco Bell like so many enchilada wrappers? Or was there a secret foreskin cemetery somewhere in Houston, perhaps in a public park, where every day the good people of Texas unknowingly picnicked atop the flesh of a thousand Jewish penises? I wanted to think that there was such a cemetery, but I wasn’t sure what I would do if I found the spot. If, like some anticircumcision activists, I had been convinced that the removal of my foreskin had caused profound physical and mental anguish, then the journey to the grave would naturally lend itself to drama. I could fall to my knees Platoon-style, pound the earth, and weep for my lost lubrication. But, having no mixed feelings about my circumcision, the journey would inevitably be anticlimactic.

Still, my foreskin had been a part of me, and I wondered where it had ended up.

“So what did you do with all the foreskins?” I asked.

My mohel shrugged. “I would just drop them anywhere and stomp them into the dirt,” he said.

“Oh,” I said.

Within a half hour, I was out of questions. “Sorry I can’t be of more help,” my mohel said.

I told him I understood, and I did. It was ridiculous to have thought that he might remember me among the thousands of babies he had circumcised.

Our salads arrived and our conversation drifted to the historical origins of circumcision. An hour came and went. When my mohel and I exhausted everything we could think to say about foreskins, our conversation somehow shifted to the history of gazpacho soup in America, a subject my mohel seemed to know a lot about.

At the end of lunch, I still had twenty-three hours left in Colorado. I got back into the Explorer and we rode into the pale brown mountains.

At one point during the drive, my mohel turned to me. It seemed something important was coming. “Did I mention that I circumcised the sons of Michael Dell?” he asked, referring to the computer mogul from Houston.

When we arrived at my mohel’s two-story ranch-style home, I met his wife and then retreated to the guest bedroom to take a nap. An hour later, my mohel tapped softly on the bedroom door. He said that he had something he wanted to show me and led me upstairs to a closet at the back of his office. I took a deep breath. I didn’t know what it would be, but I knew that something inside that closet was going to make the trip worth the trouble. My mohel looked at me and smiled. “Do you want some financial advice that will change your life forever?” he asked, opening the closet door to reveal a row of shelves lined with dozens of binders. I hid my disappointment and said that I did, and for the next hour we pored over his investment portfolio.

“Dividend reinvestment is the key,” my mohel said as we reviewed handwritten records of his holdings in the Coca-Cola Company over the last decade. “You can start with almost nothing.” He urged me to buy a subscription to an investment strategies newsletter called The Money Paper.

We still had a few hours before dinner. My mohel produced two floppy white sun hats. He put one on his bald crown and gave me the other. Then he grabbed a ski pole, his walking stick, and we hiked around his nine acres. The mountain air was hot and dry. My mohel wore a tube of ChapStick on a string around his neck and he applied it liberally. The next morning, I tried to jog his memory one more time. I had come too far to give up so easily. I took out a baby photo I had brought with me.

“Anything?”

“Nope.”

My mohel’s wife and I had oatmeal for breakfast. The Clipper ate his own concoction of grains, beans, and buckwheat groats. It looked like cat vomit.

As I packed my bags, my mohel gave me his extra copy of Menachem Begin’s biography and some blank circumcision certificates he used to fill out after he completed a ceremony. Then he and his wife drove me to Canon City, where I would catch a cab to take me the rest of the way to the airport.

We waited for the cab at a picnic table in a small park, and when it arrived I was surprised by how sad I felt to be leaving. “I feel like the boys I circumcised are part of my family,” my mohel said.

“I’m really glad I came here,” I said. Then I hugged my mohel and his wife and stepped into the cab.

For more on Sam Apple’s memoir, “American Parent,” click here.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO