Words That Shape the Jewish Future

Peter Manseau is drawn to preserving civilizations that, to many, seem long gone. Raised stringently Catholic — his parents met while his father was a priest and his mother was a nun — Manseau’s first job out of college was at the National Jewish Book Center. That gig proved to be a critical introduction to the milieu of immigrant sweatshop poetry on which his first novel is based. In the novel, the poignant memoirs of the fictional Itsik Malpesh — he believes himself to be the last Yiddish poet — are interspersed with notes from the young book worker who translates them from Yiddish, a language he is learning to get a girl.

“Songs for the Butcher’s Daughter” (Free Press, 2008), out in paperback next month, is a transcontinental marvel, celebrating a nearly forgotten nation and the trickery and richness of language between worlds. It picked up the National Jewish Book Award for fiction in 2008, making Manseau the first non-Jew to win the prize in nearly 60 years.

Manseau’s new book is a non-fiction travel narrative that mashes forensics with faith. In “Rag and Bone: A Journey Among the World’s Holy Dead” (Henry Holt), published this spring, Manseau examines relics — bones and other pieces of dead holy people — their keepers and devotees.

The author — the editor of the Washington D.C.-based religion, science and culture magazine Search and a writing teacher and a doctoral candidate in religion — spoke recently with the Forward about his new book, bad Yiddish poetry, religious road-tripping, and the perks of being a Jew by association.

Alison Gaudet Yarrow: How does a gentile write “Songs for the Butcher’s Daughter,” a novel that reads so Jewish?

Peter Manseau: I stumbled by accident into the Jewish world. I like Yiddish literature but I was captivated by the drama of those who made it. I felt camaraderie: Like writers of Yiddish literature, I had been raised in a particular religious environment and given a rigorous education. I couldn’t get away from what I had been given. I wanted to understand that through writing about it.

Did you see yourself as a lapsed Catholic translator, like the young protagonist in “Songs” who translates Malpesh’s memoirs?

I knew writing this book that one part of selling it would be that I have this peculiar religious background and that I worked in this Jewish organization, so I wanted to play with the assumption that this translator character in the book is myself; it might be easier to believe in Itsik Malpesh. Everyone assumes a first novel is going to be a thinly veiled autobiography, and I wanted to use that to my advantage.

Since Malpesh believes he is the last Yiddish poet, you say he bears this burden of collective memory. What do you mean by that?

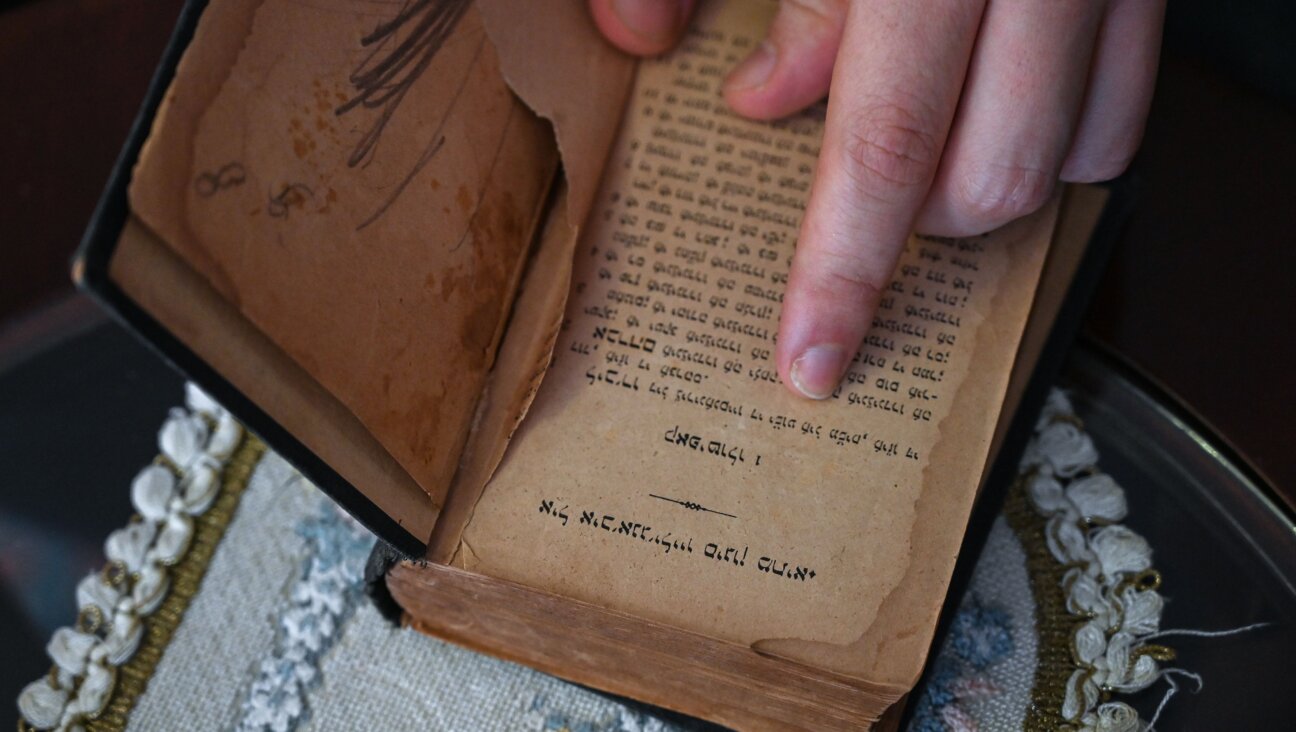

Whether or not he is the last, he believes that he is and carries the weight of this great culture. What I fell in love with … was such a culture of self-publishing. These guys worked 12 to14 hours a day in garment shops, and then they would spend an hour scribbling out poems. They would pay to put these poems between hard covers. We would find volumes of very, very bad poetry [at the National Jewish Book Center], and we would hear from family members of people who had created these books: If only their great-uncle could be discovered, then the world would know one other great Yiddish poet. It was rarely the case. The quality of the work was beside the point. What was meaningful was just the act of it, the need to create art within those circumstances.

Is the Jewish future through words, not nations or lands, like your character Minkovsky says in “Songs?

All future is through words. Nations are in flux. Words can be maintained in a way that borders cannot. That makes them powerful. It’s easy to assume that words are ephemeral, that they are easily crumpled up and thrown away, but the stories they maintain sustain us and are what we can preserve.

What is the future of the Yiddish language?

It will be there for those who want it. It’s no longer the civilization that it once was, and it never will be; that’s the mark of history. But none of that sense of revival or nostalgia should eclipse the loss.

How did you feel when you found out that you had won the National Jewish Book Award?

I was thrilled. Despite not being Jewish, I wanted to write a Jewish book because so much of what I love within American literature is American Jewish literature, and I wanted to feel that I was not barred from that conversation.

The title of your new book, “Rag and Bone,” is an allusion to a Yeats poem that references “rag and bone shop of the heart.” How did you get there?

I was writing a book about a poet simultaneously as I was writing a book about relics, so I was drawn to the idea that the technical term used for the movement of a religious relic from one place to another is actually “translation.” At the Latin root, it’s just a carrying across. I wanted to imply something about the poetry I see in these grotesque little objects that were once pieces of people.

Is there a lot of money to be made in the industry of religious relics forgery?

The history of forged relics is as old as relics themselves. A shin bone looks like a shin bone no matter if it belonged to a saint or a murder. It’s easy to rob a grave and put another label on the bones, which often happened. In the medieval period when relics were part of the economy – there was an incentive for forgery. Much less so now.

The religious road trip seems to be a trend, like the one you and Jeff Sharlet went on to write the 2005 book “Killing the Buddha: A Heretic’s Bible.”

We drove around the country for a year, finding unusual stories of religious life in America. Our point is to get at the humanity of all these people, and not just the silly beliefs. There’s a lot to be said for approaching the subject with compassion no matter what you think about it. I don’t think the world is improved or much is gained by approaching religion with the intent of making it look foolish.

How would you characterize America’s relationship with religion right now?

It’s still quite polarizing, unfortunately, and it’s still very interesting to me. It’s an ongoing story. No matter who is in charge, it’s going to shape the country in ways that we perceive and ways that we won’t perceive until we look back at it.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO