The Lessons of Leo Frank

True events: Loeterman, right, directs Will Janowitz, who plays Leo Frank. Image by Courtesy of Ben Loeterman

The sole lynching of a Jew on American soil is a story that many do not know.

On April 27, 1913, a young girl, Mary Phagan, was found strangled at the National Pencil Factory in Atlanta. Leo Frank, her Jewish supervisor from New York, claimed to be the last to see her alive, and was subsequently sentenced to death for her killing. Frank’s sentence was commuted to life in prison by an outgoing governor who found new evidence after a laborious appeals process, which went all the way to the Supreme Court, confirmed Frank’s guilt repeatedly. Livid Georgians stole Frankfrom prison and drove him more than 100 miles to be lynched near Phagan’s childhood home.

True events: Loeterman, right, directs Will Janowitz, who plays Leo Frank. Image by Courtesy of Ben Loeterman

Rife with layers of drama — sex, racism, sectionalism, antisemitism, industrialization and child labor, political corruption, and churning newspaper headlines fueling a mob atmosphere, the story of Leo Frank appears made for the movies. And a new feature-length film, which stays true to the historical record, aims to tell the story again.

A longtime, passionate critic of the criminal justice system, documentary filmmaker and PBS “Frontline” series producer, Ben Loeterman plums every shred of record on the Frank case and the events surrounding it to create The People v. Leo Frank. Interviews with authors, historians and main players’ living ancestors punctuate a dramatic storyline — replete with re-creations by actors Will Janowitz (“The Sopranos” and Seth Gilliam (“The Wire”).

The film tackles what it means to be “the other,”and explores why the seemingly outlandish social forces at work are familiar enough to be stirred up again.

Loeterman spoke recently with the Forward’s Allison Gaudet Yarrow.

Allison Gaudet Yarrow: Numerous books and movies and even a musical have been made about the Leo Frank story. Why did you decide to create a feature-length film of this sort — and why now, nearly 90 years after the events?

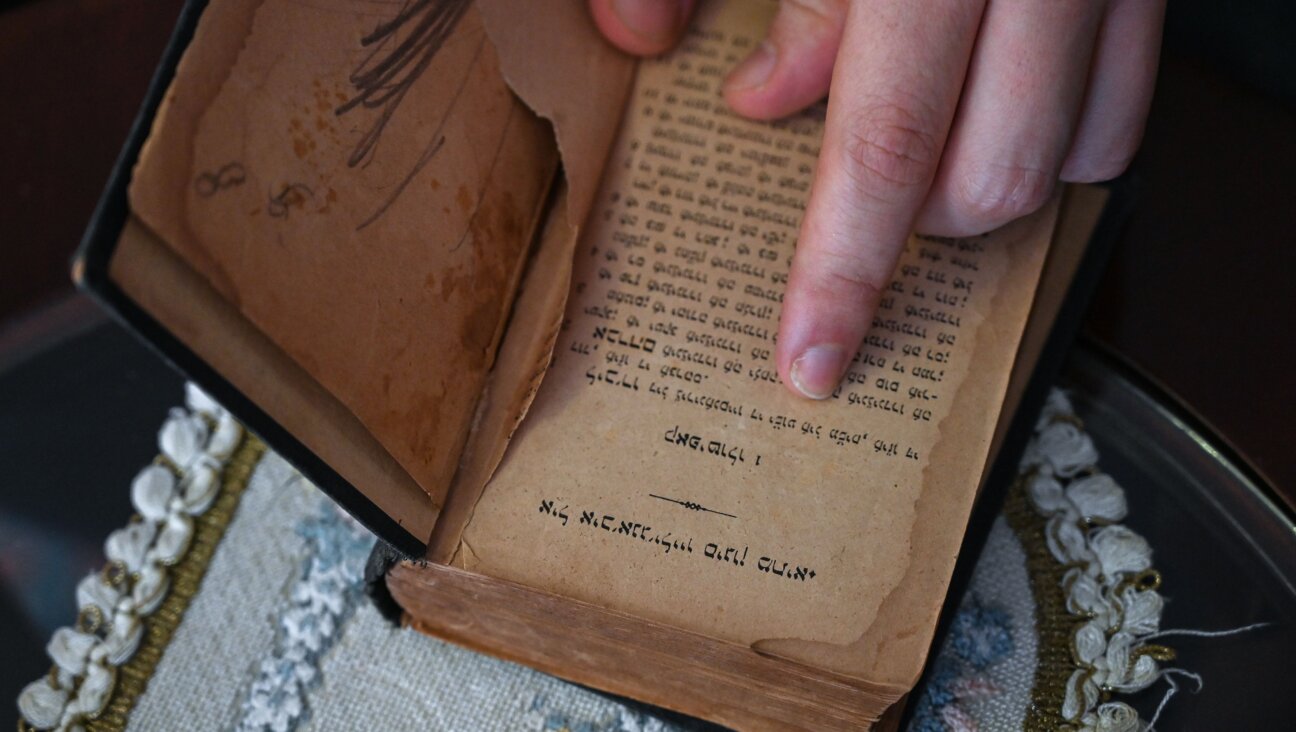

Ben Loeterman: I was shocked to learn that the case and the events around it had been treated in so many ways… . Yet there’s never been a straightforward film. We have done a period drama. We have actors. Characters speak in dialogue taken directly from the historical record. If we couldn’t find it in a transcript, a letter, a diary, an account, a report, then we couldn’t use it. It isn’t based on true events; it is true events. There is something very powerful about that.

Frank’s lynching is historically tied to the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and the birth of the Anti-Defamation League. How did you address the growing anti-Semitism leading up to the Frank case?

The Jewish community in Atlanta was well integrated and terribly assimilated. Melissa Fay Greene, who wrote “The Temple Bombing,” describes Atlanta’s Jewish community and life at the temple under Dr. Marks, never known as Rabbi Marks, she says. Hebrew? Too Jewish. Bar mitzvahs? Too Jewish. Shabbos on Saturdays? Too Jewish. It was Episcopalian Judaism, the Atlanta Jewish community’s way of fitting in comfortably at the highest levels of society. I think it is still like that. Some families who are part of that were not happy to hear that we would be telling the Leo Frank case again. I found more resistance to telling the story in the Jewish community than I did in the non-Jewish community. If you grow up with this shadow over your life. … then it’s understandable.

Why the title “The People v. Leo Frank”? Do you spend a lot of time on the case itself, which is still studied in law schools?

“The People v. Leo Frank” is used metaphorically. The point of our film and what our film succeeds most at is giving a visceral sense of otherness that Frank represented. This man is a Northerner, a Jew, an industrialist, a nervous man, a refined man, somebody who was not a good ole Southern boy. And this pitted him against people more than the simple explanation of saying he was Jewish, and therefore this was a case of antisemitism.

What was the role of the criminal justice system? Wasn’t there a point of view at the time that Jim Conley, who many now believe committed the crime, could not have lied on the stand because a black man would not have been clever enough?

Well, that’s certainly the prosecution view. The defense point of view if you want to be honest about it, was straight racist. Look at [Frank’s lead attorney] Luther Rosser’s speech. Not a word was changed, and I doubt that the delivery was very different than what we created out of newspaper accounts. He calls Conley a lying, filthy n— through whose nose tons of cocaine has been snorted. Jews don’t like to talk about that part of the case, do we? The defense made errors of commission by bringing in lots of people from New York, which didn’t mean a damn thing in an Atlanta courtroom, talking about how wonderful Leo Frank’s character was. They allowed the prosecution to end the trial by putting on a parade of girls who said, no, he had a bad character. He leered at us. He touched someone’s breast. That would have never happened if the defense had not tried to build a case around Frank’s good character. That was not good lawyering. Because of that bad lawyering, Frank’s appeals were denied.

How was Frank handed over to a lynch mob by prison officials?

It involved not a mob at all, but a conspiracy at the highest levels of government. Why are we spending so much time on this one lynching when there are hundreds of black people who were lynched under just as heinous circumstances? The answer is that this rose to a case, not of a mob — not of racism or antisemitism of the usual ilk — but to the level of state-sponsored murder.

Were there filmmaking challenges specific to this story?

If you write a novel, make a musical, do a television movie, you can create the character of Leo Frank. If you make a documentary, you are much more constrained. But if you believe like I do that the testing of the justice system is not in the easy cases but in the hard cases — not in the good people, but in the hard-to-know people — it makes it a worthwhile challenge.

The consensus among most historians today is that Frank was not guilty. What does the film have to say about Frank’s guilt or innocence?

The film never set out to retry the Frank case. I didn’t have an agenda to prove Leo Frank innocent. I truly believe there is nothing unique about the social forces at play in the Frank case that couldn’t or wouldn’t happen again in an instant. The events and the lessons they teach us are very real in the here and now.

“The People v. Leo Frank” is now being screened nationwide. For more information, click here.

The film’s trailer is below:

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO