Thoroughly Modern Marranos?

Ex Unum, Pluribus: Converso identities can illuminate the ways that acculturation and Jewish identity interact. Image by MONTAGE BY KURT HOFFMAN

The Other Within: The Marranos: Split Identity and Emerging Modernity

By Yirmiyahu Yovel

Princeton University Press, 488 pages, $24.95.

Diego Arias was born a Jew in 15th-century Spain, but his parents converted him to Catholicism following a wave of anti-Jewish persecution. Later in life, as royal chief financier of Castile, and one of the most powerful figures in the land, he enjoyed chanting Jewish prayers; ate hamin, a stew in the style of a traditional Sabbath cholent, on Saturdays, and was once seen treating a Christian saint’s effigy with disrespect. Yet he did not consider himself the least bit Jewish, and — just to complicate matters further — occasionally expressed skepticism about all religions.

Ex Unum, Pluribus: Converso identities can illuminate the ways that acculturation and Jewish identity interact. Image by MONTAGE BY KURT HOFFMAN

So, was Arias a Jew, a Christian or an atheist? In “The Other Within,” Yirmiyahu Yovel, founder and chairman of the Jerusalem Spinoza Institute, tries to make sense of the religious identity of such Marranos — the Jews of Spain and Portugal who were coerced into converting to Christianity in the14th and 15th centuries — and their descendants.

Marranism began in 1391, when Jews converted en masse in order to escape a series of anti-Jewish riots. The physical and mental pressure to convert continued, unabated; in 1412–15 alone, around 50,000 Spanish Jews submitted to the cross. Most contemporary rabbis believed them to be full-fledged Catholics who kept some Jewish traditions out of habit or nostalgia, or for social reasons. Modern Jews usually prefer to think of them rather more romantically, as secret Jews whose Catholicism was just a meaningless mask meant to protect them from the authorities. The truth, Yovel says, is far more complex, and the complexity is of a particularly modern order.

Yovel also says that Christian society was pursuing a myth of homogeneity, trying to rid itself of what it perceived as “impure” and “foreign” elements. The irony is that the conversion of the Jews did not eliminate the “other,” but rather brought it right into the heart of Christian society. The Conversos (Yovel explains in the preface that he uses the terms Marranos, Conversos and New Christians interchangeably) did not become “regular” Christians, nor were they regarded that way by Christian society. Rather, their life was marked by contradiction and duality.

Most Marranos initially took on Christianity as a superficial skin, but they could not keep up the pretense, year in, year out, of going to church and confession, venerating saints, without internalizing some of its beliefs. Similarly, they may have intended to stay loyal to Judaism, but it was impossible to practice a religion only partially, and in secret, without losing most of its essence.

The result, he says, was that most Marranos practiced a hybrid religion. “Judaizers” consciously tried to preserve elements of Judaism, often passed down through the women of the house who became quasi-rabbis, or gleaned, ironically, from lists of Jewish beliefs published by the Inquisition for informers. But while they may have lit Sabbath candles in secret, only pretended to eat the ubiquitous Iberian pork or mentally annulled their actions in church, theological confusion abounded. For example, Judaizers believed that Judaism was the true path “to salvation.” The intent may have been Jewish, but the framing theology — salvation — was Catholic. Similarly, the Marranos had a patron saint: Queen Esther, herself a hidden Jew.

At the other end of the spectrum, Marranos who accepted their new Christian faith were still influenced by their Jewish background. The Inquisition records show Marranos who preferred to baptize their children on a Saturday, because of their “affection” for the day, and New Christian monks who, because they had a clinging distrust of the polytheistic or idolatrous beliefs these practices implied, rejected the Trinity and disdained the sacrament, without intending to return to Judaism.

Conversos often tried to reform Christianity from within. For example, the patron saint of Spain, St. Teresa of Avila, insisted that true religiosity was to be found in the mind, not in actions — an attitude typical of Judaizing Marranos, who believed in one religion and practiced another. No wonder, because while she was, and believed herself to be, fully Christian, she had a father and grandfather who were humiliated by the Inquisition as Judaizers. In between lay a third group, perhaps larger than the Judaizers. These people lost interest in, or were heretical to, all religions, and preferred to dwell on the affairs of the physical world, such as business or politics, instead of seeking metaphysical salvation. But they, too, lived nominally Christian lives.

So while the Marranos may all have been drawing on Judaism and Christianity, they were effectively practicing neither. Their identity, Yovel says, was far more fluid than recognized by subsequent historians. Meanwhile, their contemporaries felt increasingly resentful of this unprecedented and unstable “other within,” and occasional bouts of violence against them erupted. Laws were enacted that prevented all Conversos from holding public office — shifting the source of their difference to blood from religion. This was a crucial shift in European thought, and one that preceded a similar shift in northern Europe by hundreds of years. The Nuremberg Laws were a result of a change in 19th century thought, but one independent of the Spanish example.

In 1480, almost a full century after the Marranos first became a social issue, the Inquisition was established to root out Judaizing Marranos (it had no jurisdiction over Jews). It also misunderstood the subtleties of the Conversos’ identity, condemning as a secret Jew anyone showing any signs of a connection to Jewish tradition. (Thus, Arias — who, to all possible scrutiny, felt nothing more than nostalgia toward Judaism — was convicted of Judaizing in a posthumous trial that destroyed his son, a prominent bishop.)

In 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella issued an edict expelling Spain’s remaining Jews. The crucial argument against them, Yovel says, was that the Jews — over whom the Inquisition had no jurisdiction — were perceived as a corrupting influence on the Marranos, teaching them how to Judaize.

Yet again, this had an effect contrary to the one intended. In response, thousands of Jews converted, thus exacerbating the Converso problem. Another 80,000 to 160,000 of the most dedicated fled Spain. Many went to Portugal, where they, too, were eventually forced to convert, replicating the problem there.

Yovel, whose outstanding, multilayered work closely integrates philosophical issues with an historical narrative, sees split identities as “a basic structure of the human condition,” but one that was legitimized only in the modern era. “In earlier times,” he says, “split identities were considered illicit and illegal, a grave social and metaphysical sin punished by the Inquisition (and later, by nationalism and similar ‘integralist’ movements).” In this respect (as well as many others expanded upon by Yovel in the two final chapters), the Marranos were harbingers — and perhaps, to some extent, catalysts — of modernity.

How unique were they? There certainly are other examples of Jews, throughout history, who mixed and matched identities, such as the Hellenizers of the Hanukkah story. Still, one parallel with modern Jewry is particularly striking. Most children of interfaith marriages today grow up in homes in which Judaism is not the only religion. Jewish holidays such as Hanukkah and Passover co-exist with Christmas and Easter; there are as many occasions to visit church as to visit synagogue; family members may openly discuss their belief in Jesus; a Passover Seder or a bar mitzvah may take on multiple religious meanings, and so on.

In “Double or Nothing?” a 2004 study of mixed-marriage families by Brandeis University professor Sylvia Barack Fishman, teenagers whose parents marked Christmas in some way generally saw themselves as heirs to two religions. In their minds, these religions co-existed as something essentially different from either mainstream Judaism or Christianity. Fishman goes on to describe an enormous, hybrid subculture of North American Judeo-Christian families, which differs “strikingly” from other American Jews of every denomination — just as the Marranos differed strikingly from their Jewish, and indeed Christian, contemporaries, sometimes even when they moved away from Spain and were able to practice Judaism in the open once again.

So as Diaspora communities continue to struggle with the increasingly urgent question of how to relate to the millions of Jews who marry “out,” perhaps some perspective can be gained from Yovel’s dualistic Marranos. Half a millennium on, they seem more relevant than ever.

Miriam Shaviv is the comment editor of the Jewish Chronicle in the United Kingdom.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

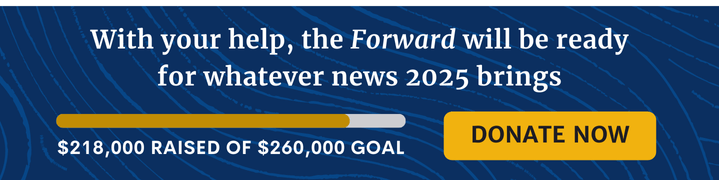

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO