Reigniting charoses traditions

Image by iStock/sbossert

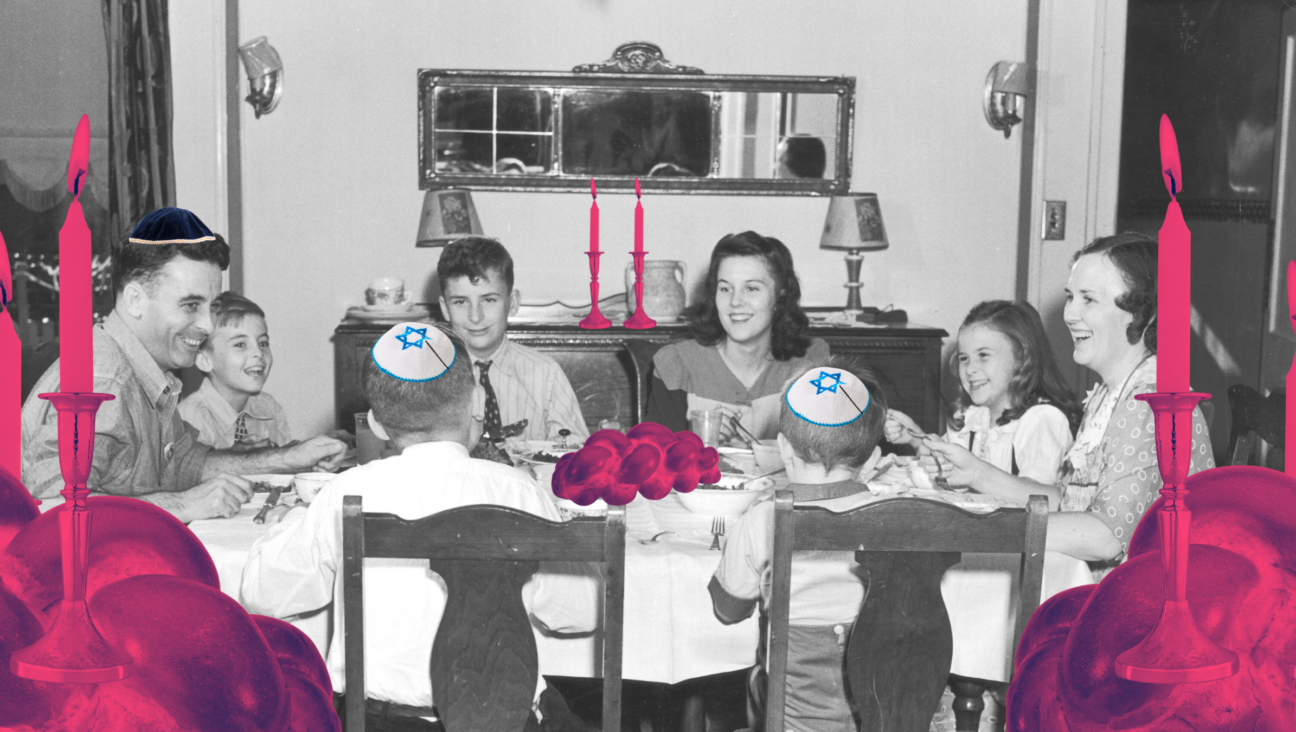

Growing up in Chicago in the 1950s, mine was the only lunch bag that trailed matzo crumbs. On coming to America we lived in a Polish Catholic immigrant neighborhood so I had no friends with whom to compare seder rituals. Despite this, Passover has always been my favorite holiday.

No other yontiff rituals compared to my father’s melodic rendition of the seder, the dramatic retelling of the exodus, the proscribed silver thimblefuls of wine, the dipping, passing, and, the mystical welcoming of Eliaju, the invisible guest. As the youngest of four children, I reveled in my feature role way past childhood. Each year, I rehearsed the “Ma nish ta nah” for days, reluctantly ceding my solo when my nieces and nephews finally asserted themselves.

During Paisech, as we called it in Yiddish, my mother prepared delicacies that took the sting off the matzo mess I schlepped to school each day. Paisech mornings I rose without my usual sloth, for I knew a “bubaleh” awaited me. This brobdingnagian matzo meal pancake, the size and depth of my mother’s black iron skillet, expunged Hostess Cupcakes from my mind all week.

Paisech was also the occasion of my mother’s rum-soaked sponge cake. Between seder wine and nibbles of rum cake I feared growing “schikker” (drunk) or having my growth stunted, as my older siblings warned. Yet, neither fear was enough to stop me.

Our seder meal included chunky apple and walnut charoses (too delicious to evoke slavery or mortar), sliced hard-boiled eggs in salt-water (the egg-soup I waited for all year), sweet gefilte fish, golden chicken soup with kneidlach (matzo balls), brisket, potatoes and carrots. No matter that she worked and had scant time, my mother’s feast never faltered.

When I was 16, I crashed into another tradition. My American-born friend Deborah invited me for second seder. As I entered her house, different cooking smells greeted me. Her father davened in unfamiliar “Sephardi” sing-song, and her mother sat at the table, unlike my mother who continuously bustled about.

That seder was a watershed experience. The Bachs were traditional, like us, so I was stymied. “Real” charoses was apples, walnuts, cinnamon and wine – my mother’s. Mrs. Bach’s was different. Didn’t a “balabusteh” like Mrs. Bach know how to make charoses? Then again, this new stuff was kind of good.

Like Dorothy in Oz, I realized I was no longer in Warsaw, from whence my parents’ traditions harkened. And my world began to expand.

When I began making seders, my toddler son and daughter helped make charoses. The “chop, chop,” became their favorite item on the seder plate. Each year the chopping increased until my late mother’s recipe produced charoses for the week.

In 2000, the last year of my eighty-nine year old father’s life, he and I talked about charoses during his childhood in Piaseczno, outside Warsaw.

“Chroyses,” he said, in his Ashkenazi-Yiddish. “Chroyses is like Jews all over the world, every country has something different.” He recalled watching his mother prepare for seder. “She klapped together an eppaleh, a pooer nissalech, a bissel wein,” he said. In the impoverished world of my father’s youth, my namesake grandmother Sarah, whom I never knew, mixed together an apple, some nuts, a drop of wine, whatever she could get her hands on to make charoses.

The Bach’s seder taught me that we Jews are a variety pack. These years, we recognize and treasure our diversity more and more. We have experienced countless trials, including the frightening pandemic that we continue to endure this year. And our cuisine has been shaped by the circumstances, spices, and ingredients available to us. Renown food writer Joan Nathan once catalogued 70-plus variations of charoses, adding that new ones are created each year.

To celebrate Jewish diversity, I propose that our seders include two charoses, one’s own tradition, as closely as possible, and a new recipe. Perhaps Moroccan balls using chopped dates, walnuts, raisins and wine, or a Libyan mortar and pestle mix of various kinds of nuts, raisins, dates, cinnamon, ginger and allspice.

Help my dear mother’s luscious charoses befriend yours or “Judy’s,” gleaned from an old synagogue sisterhood cookbook. Giten Paisech – Happy Passover.

Prywa Nuss’s Charoses

1 lb. walnuts, shelled and chopped

4-6 red apples, peeled and chopped fine Cinnamon

kosher red wine

Mix walnuts and apples. Add cinnamon to taste. Moisten with wine to bind mixture together.

Judy’s Greek Charoses

20 large dates, chopped

¾ cup walnuts, ground 1 cup raisins, chopped

½ cup almonds, chopped trace of grated lemon peel

kosher red wine

Combine fruit and nuts. Add wine to desired consistency.

Sara Nuss-Galles lives in Southern California. Her essays, fiction, and humor have appeared in Lilith, Kveller, The JTA, The New York Times and The Los Angeles Times, among others. She has been a guest commentator on NPR’s MarketPlace.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO