‘The moveable God of our ancestors’

Slowly, that sense of “at-homeness” so vital to sustaining Jewish community has begun to find a home with me and my congregants. Image by Getty Images

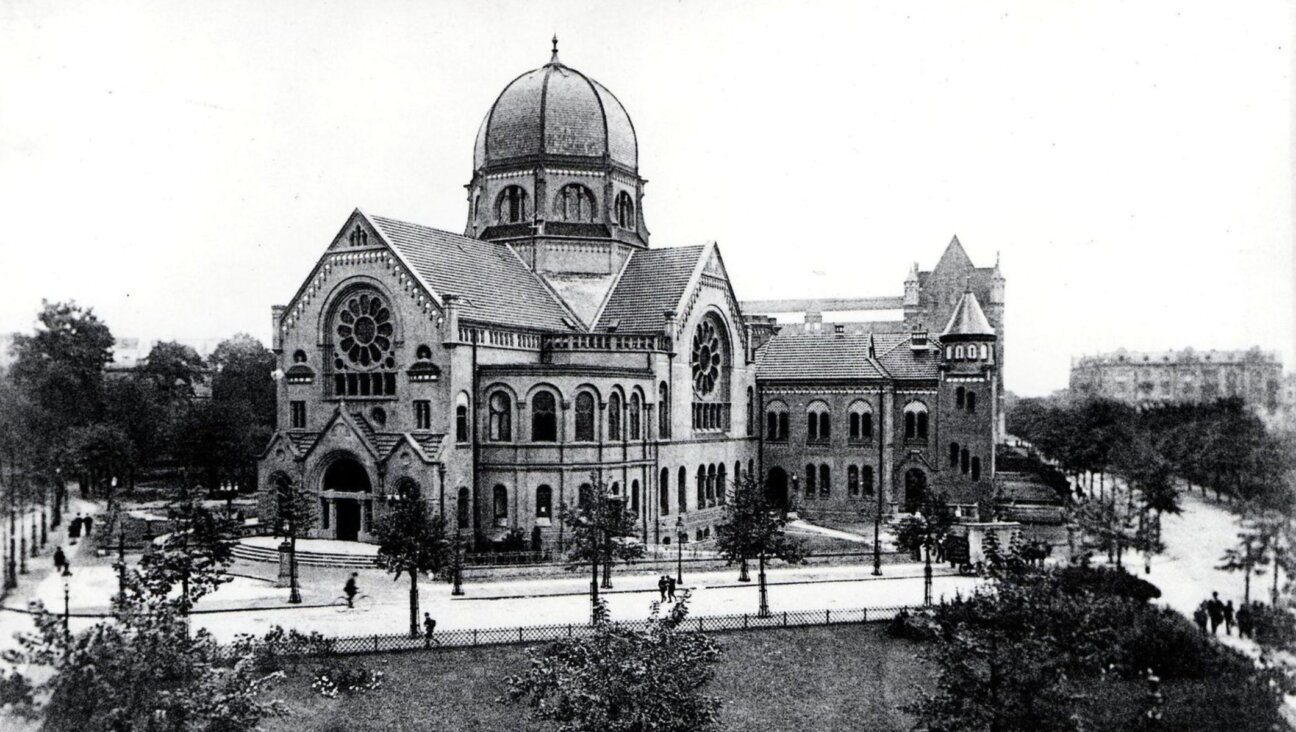

In the past few months since the beginning of the pandemic, I have several times snuck into our empty, darkened synagogue where I serve as a rabbi. It isn’t exactly sneaking: staff are permitted to enter the building to retrieve work necessities from our offices, as long as we sign in, tell our executive director we’re there, wear masks, sanitize and distance ourselves from each other upon any chance encounters.

Nonetheless, a sense of sneakiness weighs on me, as I put my master key into the main doors to our lobby or punch in the code to our offices. The insufferable quiet that now greets me in our once-bustling house of worship feels eerily like the smothering silence of a burial ground. I almost think I hear it admonishing me not to transgress the sacred line between the world of memory interrupted within and that of reality marching on “out there” in the roiling mess of America.

On my way in, I always feel a slight shudder glancing at our hand-lettered marquee which still bears the date of March 7, Hebrew date of Adar 11, the last Shabbat we celebrated together before lockdown. Like Miss Havisham’s clocks that froze at 8:40 in Dickens’ Great Expectations, the lobby sign reminds me that a community lived and breathed here until everything just stopped.

I hear ghosts flying about our sanctuary, hiding behind the Torah scrolls in the holy ark, and floating through the hallways. These are poltergeists, noisy gossips babbling about the spiritual community that just seemed to disappear, but they obviously aren’t telling the whole story.

We checked out of that space, but we didn’t disappear. True to our “nomadic DNA”, we simply emulated the moveable God of our ancestors and carried each other – our ethos along with our ethnos – into the ether of the internet. Moving our community’s life off-campus and on-line is poignantly redolent of the ancient Jewish idea that we follow God and that God also follows us in our wanderings. We are old hands at wanderings, chosen and forced.

What has always anchored us Jews is not attachments to a specific place or structure, our devotion to the land and State of Israel notwithstanding. Our enduring anchor is a sense of “at-homeness” with God and with each other that blunts the lacerative edges of displacement.

I’m no great devotee of creating community Zoom, but I’ve made my peace with it in the absence of any safe alternatives. Slowly, that sense of “at-homeness” so vital to sustaining Jewish community has begun to find a home with me and my congregants.

For instance, nothing can replace the intimacy of weekday morning services in our chapel, followed by post-worship breakfast. But Zoom services have opened wide a virtual door for members of our community who would or could not otherwise join us for prayer in person.

Folks from as nearby as my neighborhood and as far away as New York City and Washington, D.C. have joined us in the morning or for Torah study, expanding and deepening the embrace of our congregation. Their presence reminds us that local Jewish community is undergirded by a much broader embrace of family, one which is free of boundaries of space and even time. Paraphrasing an ancient Talmudic image, Shekhinah — God’s “portable” and accessible presence — seems to have no problem jumping on and off our computer screens with us.

Of course, million-dollar questions face all of us as we face-off with a future of on-line high holidays and life in extended COVID lockdown. How long will this newest iteration of spiritual portability hold and how it will affect the substance and quality of our collective life?

I for one am using as much technology as I can to stay connected and help my congregants stay faithful. Yet, as I sit in the midday silence of our empty sanctuary, the ringing echoes of our many Shabbat shul goers – the Torah readers, the daveners, the young families, the babies and toddlers, the older members, my friends – afflict me with a tinnitus of longing and regret.

The next time I see many of our members in person, they may well be much older, the little ones especially. How do I maintain relationships with people over the internet, over periods of time that might be measured in years? Our nomadic ancestors and their moveable God could move about as a community because they could literally hold each other, not just carry each other figuratively, through dislocation.

For now, I deal with some of these anxieties by drawing strength from another classic image of the ancient Talmudic tradition: the parable of the woman whose husband is on an unbearably long journey, incommunicado. Her friends tell her, “He’s either died or abandoned you. Give him up and get on with your life.”

Each time she despairs of his return she looks at her ketubah, her marriage contract, in which he has promised her his love, fidelity and support. His words don’t rid her of longing, they allow her to resolve it into a longing-with-hope that sustains her until he finally returns. So too, we Jews have the words of our “ketubah,” the endless legacy of Torah that has been our love letter from God and to one another through our long journeys of exile, homelessness, and distance from God and each other.

Let’s be realistic. Not even the loveliest words of a love letter, a person’s or God’s, can replace a caress, a smile without a mask, a wedding hora or a weeping embrace at a graveside. However, what they do for me is sustain my faith that the covenant glue holding us together has an adhesive quality far more resilient than the corrosive effects of social distancing, Zoom fatigue, and isolation. It too carries us through these darker times of darkened shuls. It will carry us back to each other when the building lights come back on and the ghosts are chased away.

Dan Ornstein is rabbi at Congregation Ohav Shalom and a writer living in Albany, N.Y. He is the author of “Cain v. Abel: A Jewish Courtroom Drama.” (Jewish Publication Society 2020)

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse..

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO