Burying a bird and borrowing a chance to mourn

I can’t grieve 90,000 people I don’t know, but I could grieve the bird that flew into our glass door.

This evening, while Nancy and I were watching the news, a bird flew into the glass door that opens onto our deck. There was the sound of an impact. A few white feathers were stuck on the screen. And, below, the bird was lying on the deck. Motionless.

Sometimes birds have hit our windows and survived. As though, as we’d say, they had “the wind knocked out of them.” Somehow, they get their wind back. We hoped this bird would too. But as minutes passed, it seemed unlikely. Nancy worried about a cat showing up while the bird was stunned. My guess was that that worry was too late.

More time went by, and it was clear the wind was not coming back. I felt deeply sad. We’ve lost birds this way before, but this was different. It was like the death of a child, an innocent, that should have been prevented. Maybe it could have been. We put shades on other windows, and that stopped birds from flying into them. No bird had ever flown into the glass door before. It seemed a unique tragedy.

Henry Greenspan

In the background, on television, the news reported that the coronavirus death toll in the U.S. was over 90,000. And predictions of twice that much by August. But anyone who has followed this knows that sometime in June is more likely. And it will keep rising.

We live surrounded by mass death. For most of us, the dead are “only” imagined. As though somewhere, on a Mount Rushmore scale, there were enormous numerals that spelled out nine-zero-zero-zero-zero. As though it was the number that had died.

I can’t grieve 90,000 people I don’t know, but I could grieve the bird that flew into our glass door. The dead bird gave me the chance to feel something specific. I could look down at it, see it, and feel terrible about it. I cannot look down on 90,000 and growing. I can only look on. And wonder what we all wonder but rarely let ourselves think about too long.

The Holocaust survivors whom I’ve known over five decades often spoke of the impossibility of mourning. The number of the lost was too large, too terrible, too overwhelming. During the destruction, most did what they could to get to the next day. Many imagined that someday they would be able to experience the grief that they could not feel then. For a few, that was the main reason they wanted to survive. None ever told me about a dead bird. But a few spoke of butterflies and the fantasy that they were the spirits of the lost, finally free.

After the war, survivors tried to grieve, but it was still an almost impossible task. “Black books” were written to chronicle the history of erased communities. Memorial services were held, generally organized and attended by survivors alone. There were some plaques and prayers. In later years, many survivors told me that, for them, the museums serve as missing graves. They try to imagine that their dead are now there. They say they need a cemetery somewhere, even while they know they are pretending.

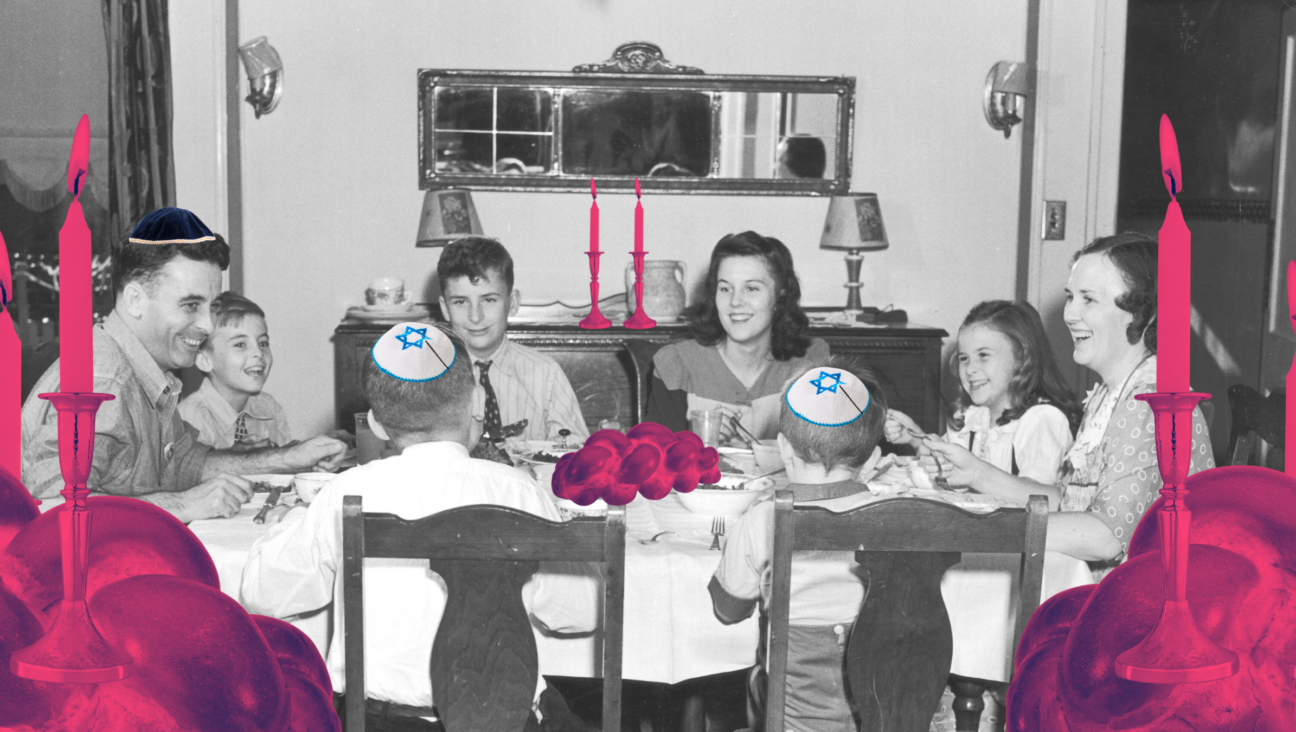

Agi, an Auschwitz survivor, was one of my closest friends for thirty years. We wrote a book together. We schmoozed and smoked together. She and her husband, Zoli, held up one corner of our chuppah.

Agi’s father survived the war and lived into the 1970s. She once told me that a friend, another survivor, asked if she could visit Agi’s father’s grave to say Kaddish for her own father, who had not survived. The friend had asked her rabbi, who said it was OK to borrow Agi’s father’s grave. And so, over many years, the grave of one father served to grieve another.

I buried the bird in a small grove of pines in our backyard. It is a spot Nancy and I call “Hank’s mountain.” When we first moved into our house, I transplanted some small saplings there. The pines — two white and one red — are now nearly twenty feet tall. I think of them as my children. And I thought they would provide good shelter for the bird that flew into our glass door and died on our deck.

In the midst of this hellish pandemic, I remembered Agi and Agi’s friend. I also borrowed a grave, and a chance to grieve, that I profoundly needed.

Henry Greenspan is a psychologist, oral historian, and playwright who recently retired from the University of Michigan. The core of his work for almost fifty years has been interviewing, writing about, and teaching about Holocaust survivors.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO