Physicist Mildred Dresselhaus, ‘Queen Of Carbon,’ Dies At 86

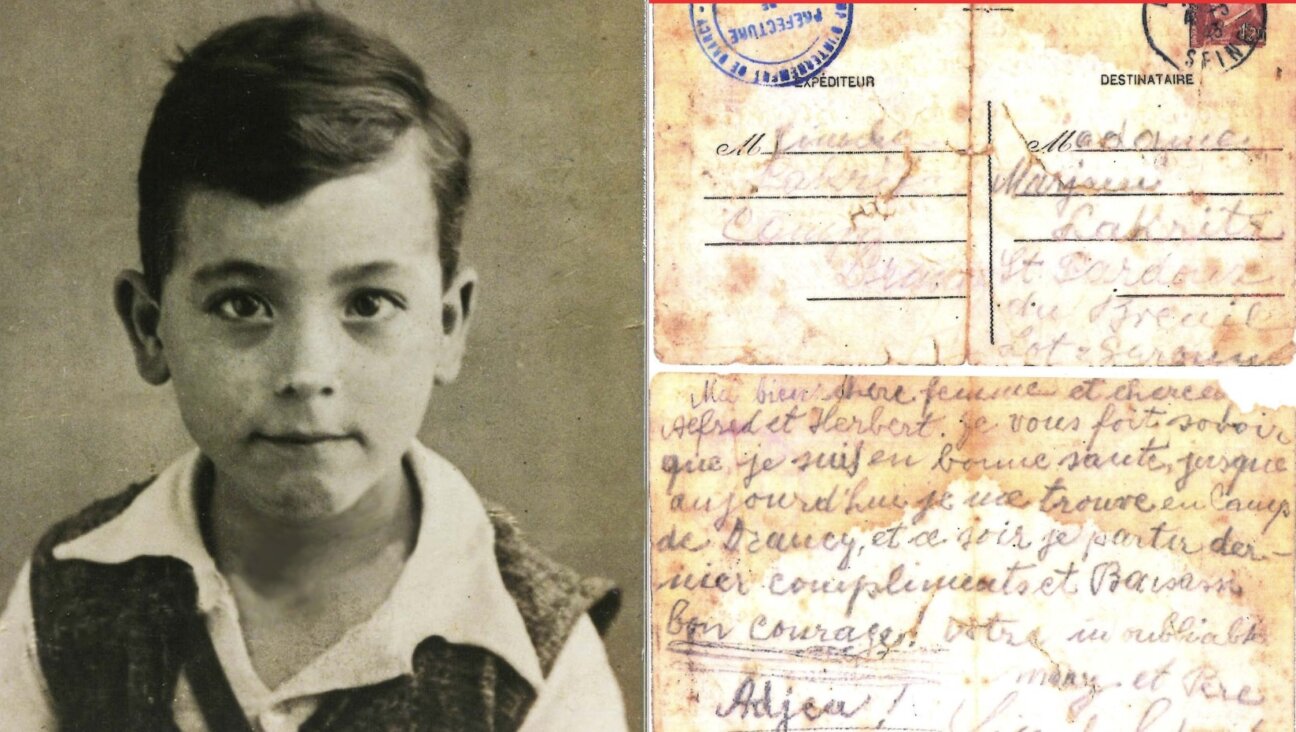

Mildred S. Dresselhaus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA, stands on stage after receiving the prestigious 2012 Kavli prize for nanoscience, in Oslo, on September 4, 2012. AFP/Getty Images Image by Getty

(JTA) — Physicist Mildred Dresselhaus, the daughter of impoverished Polish Jewish immigrants whose pioneering research into the thermal and electrical properties of carbon earned her the nickname “Queen of Carbon,” died February 20. She was 86.

Dresselhaus’ research was foundational to the field called nanoscience, in which matter is manipulated at an atomic and molecular level. Her pioneering work earned her the million-dollar Kavli Prize in Nanoscience in 2012, the National Medal of Science, the Presidential Medal of Freedom and IEEE Medal of Honor, the highest award of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

She also was an advocate for women in science fields, and gained wider fame in recent weeks thanks to her starring role in a television commercial promoting General Electric’s efforts to promote women in science. The commercial, titled “What If Scientists Were Celebrities?” imagines a world in which young girls dress up as Dresselhaus, glossy magazines feature her on their covers and gossip columns keep tabs on her comings and goings.

Abbi Jacobson, the Jewish actress who stars in “Broad City,” appears briefly in the ad as a Dresselhaus fan.

Mildred Spiewak was born in Flatbush, Brooklyn in 1930 and grew up in the Bronx. “The Bronx, I remember, was a very poor neighborhood but that was all that immigrants could afford at that time,” she recalled in a 2013 interview. “Life was tough. I grew up — my father didn’t have a job but there weren’t too many people who did have jobs.”

The prestigious Bronx High School of Science was not open to girls in her day, so she attended the selective Hunter College High School in Manhattan. She received a bachelor’s degree in 1951 from Hunter College, where she took an elementary physics class with another daughter of Jewish immigrants, Rosalyn Yalow, a future Nobel laureate in medicine. Dresselhaus often said it was Yalow who pushed her to go down the path of science and physics, at a time when educated women were expected to become secretaries, nurses or teachers.

Dresselhaus went on to earn a master’s degree from Radcliffe College and a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago.

Two years after her marriage to fellow physicist Gene Dresselhaus in 1958, both were offered faculty positions at MIT. In 1968 she became a professor at MIT, where her research led to advances in carbon-based materials used in solid-state electronics. She is survived by Gene, their four children and five grandchildren.

As early as the mid-1970s she became a public advocate for women in engineering and science, and mentored countless young women during her time at MIT.

Later in her career, MIT named her institute professor emerita, its highest distinction, and she continued teaching and researching until shortly before she died.

“I’ve been lucky,” she said in 2013. “I’ve been at a place that’s a meritocracy. It doesn’t really matter that much what your gender is if you do the work well. I think women benefit from being in places and having positions where the quality of work is the criteria, not what you look like. Not every place is like that.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO