When History Is Closed for Debate

The spirit of the holiday season has just swept across the French National Assembly. On December 22, the nation’s representatives — or, more accurately, the handful in attendance — passed a bill that would criminalize the denial of the Turkish massacre of the Armenians in 1915.

It was as much a gift to the government of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who will surely use it to bolster the great swell of Turkish nationalism he has been riding, as it was to the French-Armenian community, whose votes Nicolas Sarkozy’s government has been desperately courting. Though the bill must pass several more hurdles before it becomes law, there has already been less damage to Franco-Turkish relations — they hardly could have gotten worse — than to our relation with history.

Historical revisionism has a long history in France; it also has a different name: negationism. Historian Henry Rousso coined the term nearly two decades ago in his book “The Vichy Syndrome,” while Alain Finkielkraut had anticipated it with his essay “The Future of a Negation.” It was, as well, the preferred term for ancient historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet, who, in his 1993 book, “Assassins of Memory,” made a simple but critical distinction. Revisionism is what historians do every day — namely, examine and reconstruct the past in light of new discoveries or insights. Negationists, on the other hand, simply deny the existence of certain past events.

Instead of revising the past, they bury it. Since, as Vidal-Naquet observed, dialogue requires a common ground based on truth, historians share as much with negationists as firefighters do with arsonists.

Negationism came of age in postwar France as the nation wrestled with the legacy of Vichy and the Final Solution. With every empirical advance made by a generation of historians like Robert Paxton and Michael Marrus that deepened our understanding of France under Vichy, there appeared the works of “revisionists” like Robert Faurisson or Maurice Bardèche, who, rather than reinterpreting the past, reinvented it. Perhaps not coincidentally, both men taught French literature, not history, thus freeing them from the usual constraints of material evidence and historical methodology.

Perhaps inevitably, the struggle over the past in France spilled beyond the academy into the courts. The succession of trials, ranging from Paul Touvier and René Bousquet to Maurice Papon, all of whom were accused of committing crimes against humanity during the Occupation, led to the passage in 2006 of the Gayssot Law, which criminalized the denial of the Holocaust. It also turned professional historians into professional trial witnesses. At Papon’s trial, in 1997, several eminent historians, including Paxton, were called to give historical evidence during the hearings. By the end of the trial, the line between the “judgment of history” and the actual judgment by a jury had blurred irreparably, discomfiting both the legal and historical professions.

One of the few historians who refused to testify was Rousso, who worries over our age’s growing fascination with a “juridical reading of history.” Such a reading, Rousso claims — and which explains his refusal to testify at the Papon trial — necessarily undermines the integrity of history. As he argues in his book “The Haunting Past,” the historian’s presence on the witness stand forces him to speak ultimately to one thing and one thing only: the culpability of the defendant. When it comes to reflecting on the complexity of the past, however, the courts are as intolerant as are the negationists they are bringing to trial.

The irony is clear: The effort to protect the past from negationists who seek to destroy it has instead placed it in the embrace of politicians who, in codifying it, wish to remove it from the realm of public debate. It is for this reason that several prominent historians, led by Pierre Nora, have criticized the new law. By “freezing” this historical event — in other words, removing it from the realm of professional and public discourse — the law prevents historians from doing their job. “History is above all else a source for debate and for the sake of democracy must remain so,” wrote the historian Christian Delporte in a blog post for Le Monde.

There is no doubt that if Vidal-Naquet were still alive (he died in 2006) — this new law would have outraged him. Born into a Sephardic Jewish family, as was Nora, Vidal-Naquet signed a petition shortly before his death that demanded the abrogation of the Gayssot Law. Seventeen of France’s most prominent historians joined him, including Nora. While France’s government is busy playing with history for political ends, we should recall the concluding words of the petition: “In a free society, it belongs neither to parliament nor the courts to define historical truth.”

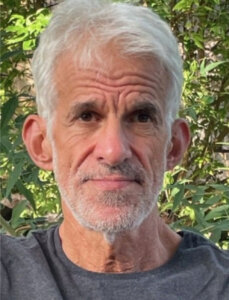

Robert Zaretsky is a professor of history in the Honors College at the University of Houston. His most recent book is “Albert Camus: Elements of a Life” (Cornell University Press, 2010).

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO