Rooms Packed to the Brim With Life

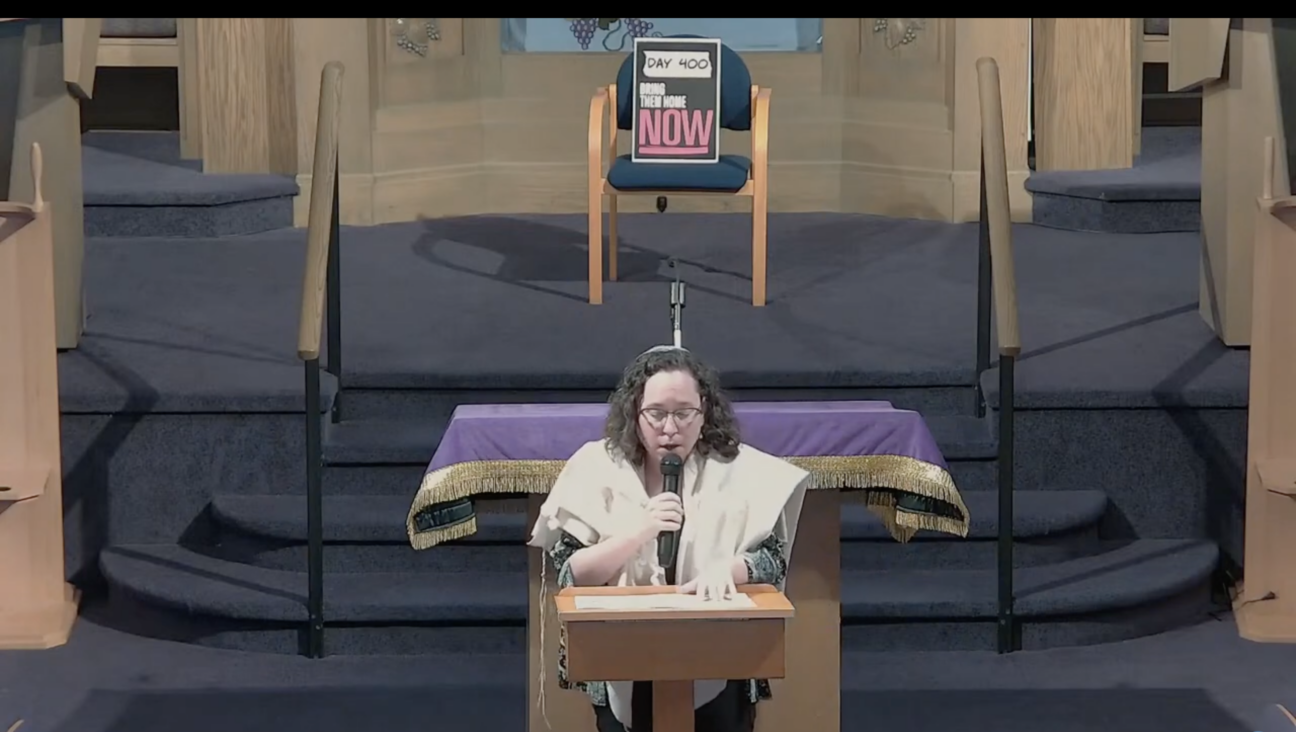

Comforts of Home: Jenna Weissman Joselit dons 3-D specs to visit the 1930s Berlin apartment of Yair Noam, né Manfred Nomburg. Image by Maya Zack

Funny how things turn out. In last month’s column, where I discussed my trip to the Stanton Street Shul, I made much of the fact that I did not have to resort to 3-D goggles to be transported back in time to the Lower East Side of the early 1900s. But, as luck would have it, this month I actually did don a pair of 3-D specs when I visited (if that’s the right word) the 1930s Berlin apartment of Yair Noam, né Manfred Nomburg.

Currently on view at the Jewish Museum, Noam/Nomburg’s childhood home has been imaginatively reconstructed by Maya Zack, an Israeli artist, in an installation that bears the name “Living Room.” Drawing on Noam’s sharply etched memory, she furnished, and then photographed, a series of rooms that are chock-a-block with the appurtenances likely to have been found in a middle-class Jewish home in prewar Germany: an umbrella stand, a piano, a bit of greenery in the wallpaper and in the form of planters, a comfy sofa, bookshelves and an armoire where a pair of Sabbath candlesticks are tucked away.

It’s all very appealing and accessible, and poignant, too. That the installation is housed in what had once been the home of another German Jewish family — the Warburgs, whose good fortune is captured by the high ceilings, dark wood doors and abundant ornamental trim of the second floor gallery — provides another layer of resonance to the proceedings.

So, too, does New York Jewish Museum’s institutional history. More than 20 years ago, in the fall of 1990, the museum was the site of “Getting Comfortable in New York,” an exhibition about the American Jewish home that I curated together with Susan Braunstein, who now heads the museum’s Department of Judaica. Moving over time and space through a series of built environments, from the exterior of a tenement to the interior of a 1950s rec room, “Getting Comfortable” brought home the various meanings that upwardly mobile American Jews attached to their domestic lives. I, for one, couldn’t help but recall it when making my way through “Living Room,” which, in part, occupies the same space that “Getting Comfortable” inhabited years earlier.

Layering, then, is key to the visitor’s encounter with “Living Room,” which is where the 3-D glasses come into play. They provide depth, both literally and conceptually. Wearing them, we see more clearly the relationship of the objects in the room to one another and to the well-upholstered life characteristic of middle-class Berlin Jews. And yet, the act of putting on and taking off the glasses also distorts and disorients, causing a rupture — a disconnect — between the past and the present. It quite literally changes our perspective. Perhaps that’s the point.

Sound is another, though arguably less central, component of the installation. It, too, is a mixed bag, at once distracting and comforting. Nomburg/Noam’s reminiscences fill the air as he — or more to the point, an actor playing him — recalls the radio that introduced him to classical music and the sofa whose cushions made the prospect of a Sunday afternoon nap awfully inviting. This running commentary on the apartment’s contents has the effect of making the installation a lived-in space, not a shrine.

More of an exercise in the power of memory than an inventory of lost objects, “Living Room” is designed to be evocative rather than literal, to put us in mind of a certain sensibility, a way of being in the world, a moment in time. As we take stock of the apartment’s contents, we are also prompted to think about how we experience the past: obliquely or straight on. Throwing down a kind of cultural gauntlet, this multimedia artwork tests the ability of contemporary audiences to remember the details of the living spaces in which they grew up. Given the right set of rules, “Living Room” could be construed as a post-modern version of a parlor game.

All the same, it’s serious business. The installation, along with the memories that sustain and structure it, underscores the extent to which all of us — the Nomburgs, the Noams, the Warburgs and the Joselits — are shaped by the conventions, the social practices and the seemingly humble stuff of domesticity. Whatever its register, the Jewish home has left an indelible imprint on the modern Jewish experience. At once a physical and an emotional space, it also exerts a powerful hold on the imagination, where it alternately contains and constrains us and, as “Living Room” would have it, even sets us free.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO