‘Everywhere, there was death’: The Forward’s groundbreaking coverage of disaster in Ukraine — in the 1930s

The Forward’s reporting became a primary source of American information on the Holodomor, a devastating famine.

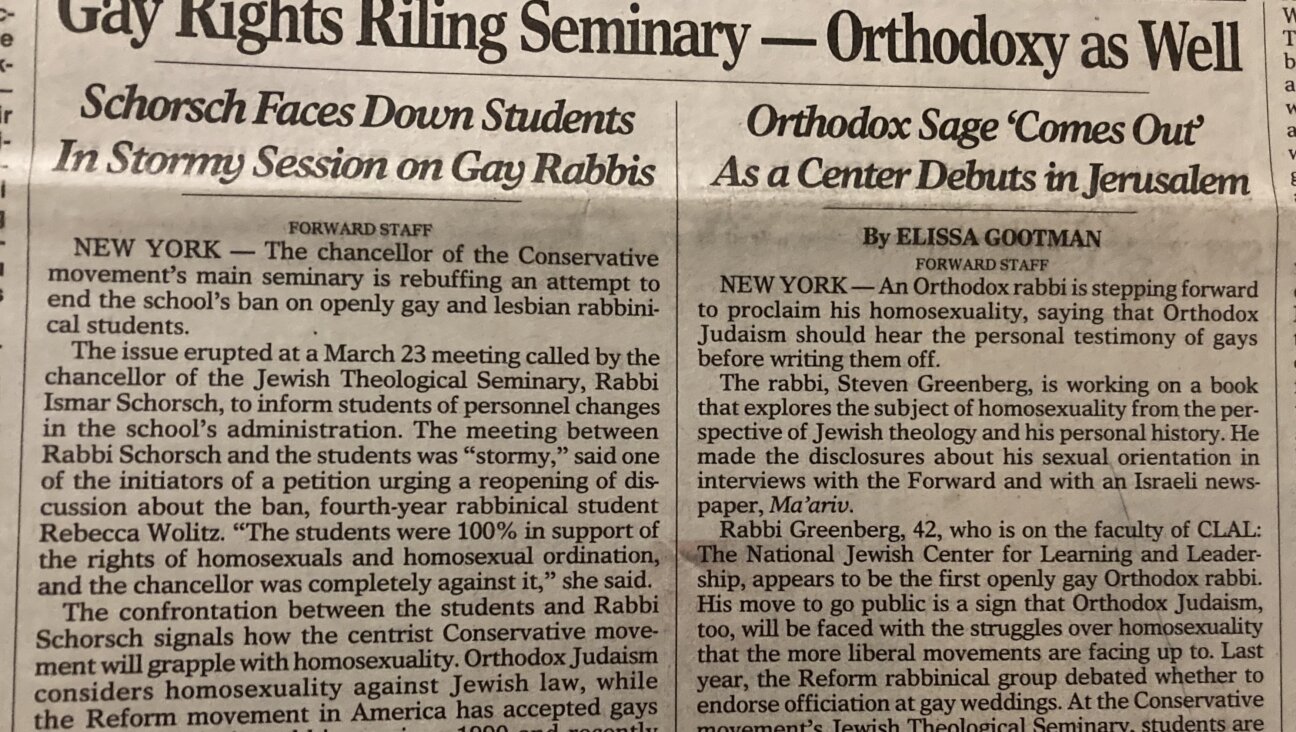

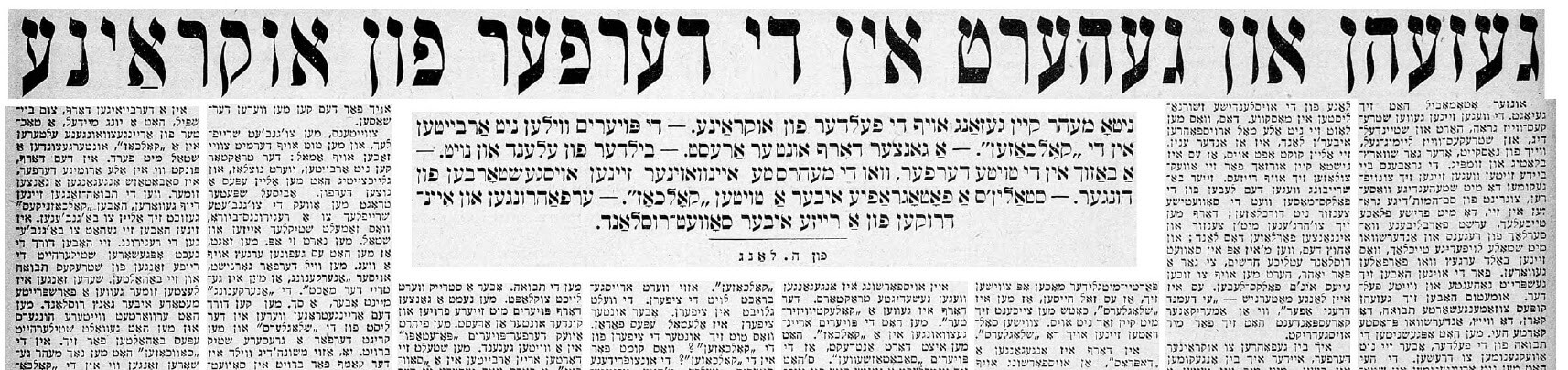

One of Harry Lang’s Forward reports on the famine in Ukraine, published on Dec. 27, 1933. Courtesy of Forward Archives

To mark our 125th year, we’re highlighting the remarkable journalism our predecessors published. First up: The reporters who fought the engine of the Stalinist state to report from Ukraine during a devastating famine. This article was originally published as a newsletter — sign up here.

It was a poetic sub-headline: “No more singing in the fields of Ukraine. The peasants don’t want to work on the kolkhozy.”

The story beneath was far grimmer.

Millions of Ukrainian peasants were starving and dying, succumbing to a brutal famine now known as the Holodomor. They didn’t want to work on the kolkhozy — Soviet state-run collective farms — because the existence of the kolkhozy was killing them.

Harry Lang, a labor activist who joined the Forward as labor editor in 1916 and would stay on staff until his death in 1950, was on a reporting journey through the Soviet Union in 1933 when he came to the rotting fields of Ukraine. The crops had spoiled, and much of the little that had been successfully harvested had been confiscated in retribution for missed quotas.

Under Joseph Stalin, the Soviet government had violently forced Ukraine’s subsistence farmers to give up their land and long-cultivated agricultural practices in the name of collectivization. The result, Lang reported, was a system that made it impossible for peasants to find enough food, no matter how productive their kolkhozy were.

“Everywhere we see piles of raked-up grain — here corn, there wheat, somewhere else plain hay fodder,” Lang wrote under that lyrical headline on Dec. 27, 1933. “The grain has been cut down from the fields, but no one has taken it away to thresh. The hay has not been taken away to the stables. The piles of grain and hay are already soaked and have begun to rot.”

And everywhere, there was death.

Peasants suspected of sabotaging farm equipment or operations — a common form of protest — were “shot on the spot,” Lang reported. In a village he described as filled with “cemeteries of houses,” one resident said that half the population had died of starvation.

There were graves everywhere. The resident told Lang of a local girl who had watched her mother bury her father, then later buried her mother and brother herself. “Same thing over there,” he said, pointing toward another village. “And in another area, just over there, also.”

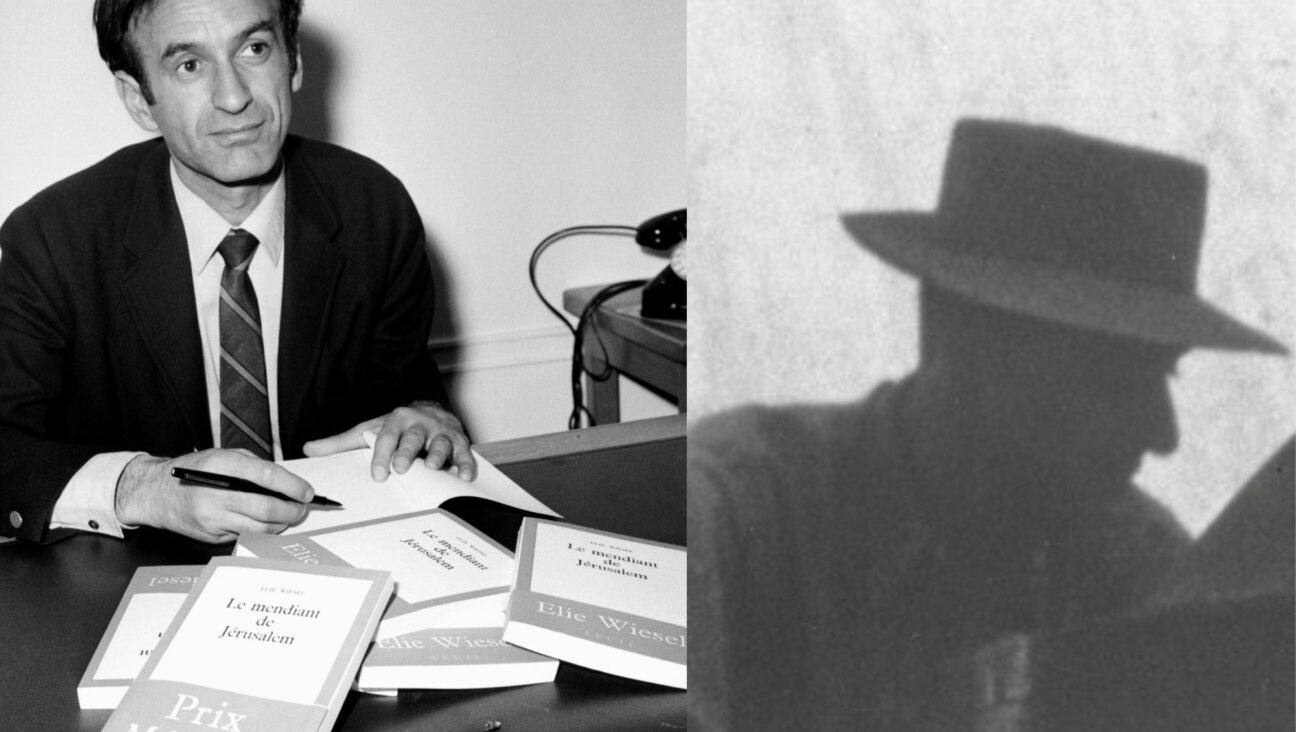

On Dec. 30, 1933, Lang reported on “A Visit in the Jewish Kolkhozy of Ukraine and White Russia.” Courtesy of Forward Archives

That Lang was there to witness the horror was improbable. Many people he had encountered elsewhere in the Soviet Union thought that his plan to visit Ukraine was pure fantasy, since Stalin’s regime was doing everything in its power to suppress news of the famine. “To allow foreign correspondents there,” Lang wrote, “was not in Moscow’s interests.”

Yet Lang managed to worm his way in, with a passport sanctioned by the regime. And he wasn’t the only one. The Forward’s Mendel Osherowitch, who had been born in Ukraine, had written a series of dispatches from the same turmoiled terrain over several months in 1932, including an account of a visit to his home shtetl, where alcoholism had become rampant in response to the famine: “Drinking is explained by the fact that bread costs 12 rubles 50 kopecks whereas a liter of vodka costs 2 rubles,“ he wrote.

Between the two men, the Forward’s reporting became a primary source of American information on the Holodomor, especially after some of Lang’s material was reprinted in English in the New York Evening Journal, a Hearst newspaper, in 1935. That publication was one of the first to introduce the American public to the scale of the famine, which Lang wrote had by 1935 claimed some 6 million lives. (Historians continue to debate estimates of the Holodomor’s death toll, with many arguing it was around 3.9 million.)

In April 1932, Osherowitch reported from the Soviet Union that “From the Small Towns Jews are Running to Moscow.” Courtesy of Forward Archives

There were other repercussions, too. As Gennady Estraikh, one of the experts in this phase of the Forward’s history, has written, Lang’s groundbreaking reporting on Ukraine led to his expulsion from the Socialist party. He only escaped being fired from the Forward, Estraikh noted, because its founding editor, Ab Cahan, announced that if Lang went, he would, too. The Forward’s general manager, Baruch Charney Vladeck, was forced to resign, although he later withdrew his resignation.

Ninety years later, the Forward’s reporting on that famine feels newly relevant.

Stalin is long dead and the Soviet Union and kolkhozy alike dissolved. Yet once more, journalists are risking their lives to cover a human-inflicted humanitarian disaster in Ukraine, this time the result of Russia’s assault on its neighbor. The Committee to Protect Journalists counts seven reporters and photographers killed so far. Like Lang and Osherowitch, these brave reporters are bearing witness, uncovering horrors and making sure the whole world sees and understands what is really happening on the ground.

As in 2022, so in 1932. In one of Lang’s articles in the Journal, he wrote of a Jewish woman he found carrying the corpse of her child — her second to die in a month — to the cemetery. Her husband was dead, and all her living children were “bloated from hunger,” Lang wrote. When a man Lang enlisted as a grave-digger took away the little body, the woman began to weep.

“‘There are still people with hearts left in the world,’” she cried. “And I,” Lang wrote, “a stranger from faraway America, wept with her.”

Quotes from Lang’s articles were taken from a translation done by Moishe Dolman, and originally published in the journal Holodomor Studies in 2010.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO